Q&A on the South Australian energy “crisis”

South Australia has become a world leader in the integration of intermittent renewables. The state now has around 41 per cent of its electricity generation supplied by wind and solar. This is more significant given South Australia’s geography: it sits at the edge of the National Electricity Market (NEM), with no access to hydro or other zero emissions firm generation, and only constrained (25 per cent of peak demand) interconnection to Victoria.

Recently there has been intense scrutiny in the South Australian electricity market following big increases in wholesale electricity prices which resulted in the South Australian Government asking for an extra gas power station to be brought back into service. This has impacted on the costs paid for electricity both by South Australian industrial and residential customers, which has, in turn, raised questions about the role of the high levels of renewable energy.

Electricity markets and systems are inherently complex. We look at some of the common questions, claims and misconceptions about the situation in SA and what it means for how we decarbonise our energy supply in Australia.

Q: Is there an energy crisis in South Australia?

A: Not really. Crisis infers a sudden problem, whereas the challenges in South Australia have been coming for a while. South Australia saw a sharp increase in baseload wholesale prices compared to other states in the eastern seaboard in 2015, when the owners of the Northern power station announced it would close in May 2016.

In recent weeks there have been further spikes in the spot price for wholesale electricity. This was the result of a coincidence of factors: (1) constraints on the main interconnector between SA and Victoria, which is in the middle of being upgraded (2) periods of very low wind generation (3) a cold winter increasing demand. The remaining gas generators in South Australia found themselves needing to increase output substantially to meet demand. While they had contracted some gas to generate power, they needed to go and buy lots of extra gas quickly to ensure adequate supply. They therefore bought gas on the spot market, which is more expensive, and this exacerbated already higher wholesale prices in South Australia.

For more information go to: South Australia's (re)balancing act

Q: So what has this got to do with renewables?

A: South Australia is a constrained grid. It can rely on around 25 per cent of its maximum demand from electricity imported from Victoria, and the rest has to be supplied inside the state. Over the past decade successive state governments have actively encouraged the uptake and investment of wind and solar PV technologies. Around 25 per cent of South Australian households have solar PV systems, and the state hosts around half of all the wind farms in Australia. These combined add up to around 41 per cent of the state’s total electricity supply. This is now very high by global standards. The key characteristic of these technologies from the perspective of how they impact the electricity market is not that they are renewable, it is that they are intermittent in nature.

At low levels these intermittent technologies tended to operate at the edge of the grid. They generated when it was windy and sunny, but they didn’t have a significant impact on the overall system. As the levels of renewables increased they began to affect the viability of the existing fleet of thermal (gas and coal) generators. When the wind blew strongly the wind turbines would generate large amounts of electricity, meaning many of the thermal generators had to turn down, or eventually switch off. This reduced greenhouse emissions (the core purpose of renewable energy) and it also began to affect the viability of the thermal generators (a corollary of this core purpose).

Many of the larger and older thermal generators were designed to run all, or most of the time. It was expensive and inefficient to try to turn them on and off to adjust to increasing levels of intermittent generation from renewables. So they began to close. Playford power station was mothballed in 2012. Half of two gas power stations were scheduled to be mothballed from next year and eventually Northern announced it would close in May this year.

The effect of this closure was to reduce supply without any material change in demand. This scarcity resulted in an increase in the baseload wholesale price for electricity. So the underlying price increase was largely caused by the closure of Northern power station, and the closure of Northern power station was largely caused by increased renewables.

It’s true that Northern and Playford were old power stations that were reliant on a declining fuel source. So they might have closed in the near future in any case. But in the days before renewables and other carbon abatement policies, this would simply have provided a signal for someone to build a new (probably gas-fired) plant to replace them. The fact that this hasn’t happened and indeed, some of the existing gas stations have either reduced capacity (Pelican Point) or announced closure (TIPS A, since rescinded) is a clear sign that the viability of the thermal plant in South Australia has been reduced.

Q: But don’t more renewables lower electricity prices?

A: No. Electricity is a commodity market where supply and demand has to match all the time. This is a highly complex process that has been significantly improved by the creation of a national electricity market in the 1990s. The electricity market trades around the clock. Prices can and do fluctuate wildly. The primary effect of these price fluctuations is to signal the need for more or less generation, both in the short run, by switching existing plant on and off, and in the longer term, by signalling the need for new investment or exit of existing plant.

Because the commodity is not storable the spot market is volatile. As a result around 80 per cent of electricity is bought and sold in futures contracts, mostly by large electricity users (industrial customers, retailers) buying from generators. It helps manage risks for both generators and customers, which is cheaper for everyone in the long run.

In practice, only firm generation plant (conventional power stations, including hydro) can sell electricity futures. An intermittent generator cannot safely sell futures because it doesn’t know if it will be generating at the time that power prices are high (which is the only way the contracts can be used to manage price volatility). So there are broadly two markets for electricity and two prices – the spot price and the contract price. In South Australia the contract price has increased with the closure of baseload capacity in that state. This accounts for most of the cost of electricity.

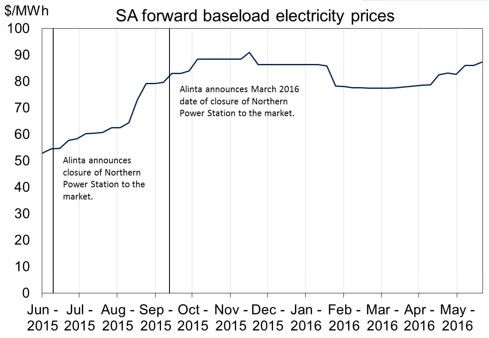

Figure 1 South Australia’s forward contract (2017) baseload electricity prices

Source: NEM Review, 2016

Periods of high wind and/or sunshine can lower the spot price in South Australia, similarly still evenings will tend to see them increase. If retailers/large users have contracted out their expected loads, then the spot price functions as a balancing mechanism, so any savings here have only a marginal effect on the overall cost, which is primarily driven by contract prices.

Q: Can technologies like wind and solar replace coal and gas?

A: Only partially. Intermittent technologies like wind and solar are not a like-for-like replacement for dispatchable generators like gas, coal and hydro. There are two big differences.

First, intermittent technologies, by their nature, cannot be guaranteed to turn on at times when they are most needed, like cold snaps and heat waves (which in turn contributed to recent electricity price spikes). This means some sort of back up or dependable alternate source needs to be found. In the case of South Australia, relying on Victoria for back up may be increasingly risky in the future, when some of Victoria’s older brown coal power stations close. The market operator is forecasting declining flows into South Australia after 2019 in anticipation of this.

Second, current wind farms and solar are not able to provide power quality services, in particular the ability to manage the frequency of the electricity grid. It is essential for the safe operation of the grid that voltage and frequency are managed inside prescribed narrow ranges (around the optimum levels of 240 volts, 50 Hz, respectively). To date we have used large thermal generators to do this, but in the rapidly approaching future, there will be times when there will be very little firm generation available to supply these services.

For more information: Power quality: the Dark Side of the Moon

There are a range of solutions to both of these challenges, each of which will add additional cost to the operation of the network. It would be useful to have a considered, strategic and national approach to this, ensuring the most effective options are chosen. Given uncertainties about how supply and demand may evolve the future, the best value approach is likely to involve using markets to uncover the most efficient solutions. But this will only work if governments can refrain from intervening further in the system.

For more information: South Australia renewables: Incidental learnings

Q: Should we just stop building renewable energy?

A: No. Renewable energy already plays an important part in our energy system now, and will be an important technology to help meet our greenhouse emissions targets. We will need more renewable energy as we reduce emissions, given that other very low/zero emissions technologies are either currently illegal (nuclear) or have not been proven up at sufficient scale (fossil fuel plant with carbon capture and storage). The challenges in South Australia are not a renewables problem as much as they are a planning and policy problem.

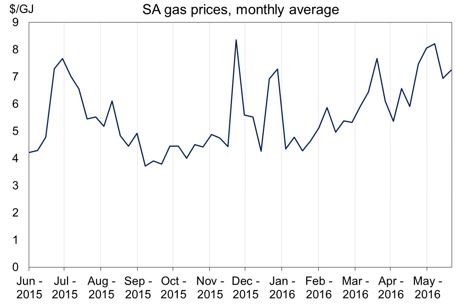

Q: Aren’t rising gas prices the main driver of South Australia's higher electricity prices?

A: Only partly. South Australia is now more reliant on gas, at a time when gas prices are relatively high. This will continue to influence the cost of electricity in South Australia. But baseload wholesale prices increased months before a spike in spot gas prices. Gas will be a contributing factor, but not the only factor.

For more information: Demand growth to dwarf gas production

Figure 2: average monthly gas price into Adelaide (ex post STTM)

Source: NEM Review, 2016

Q: So what’s the solution?

A: The challenges in South Australia reflect the challenges we face across Australia. With the exception of Western Australia and the Northern Territory, Australia operates a national electricity market, and decisions made in one state can, and often do, impact on others. As we continue to reduce the greenhouse emissions of the system, we will be using more low and zero emissions technologies, and operating the system differently to the way we have operated in the past. This requires clear thinking and careful planning to ensure the transition occurs at the lowest cost and with continued high reliability.

The current and future challenges in South Australia could have been avoided or minimised with better planning and a national approach to energy and climate policy. For example, in the short run it might have been useful to find a way to keep the Northern power station on line until the interconnector upgrade was completed and the winter peak was over. In the longer run a continuing moratorium on new gas fields in the Gippsland Basin and potential closure of some Victorian brown coal power stations could exacerbate already challenging conditions in places like South Australia.

Renewable energy is popular, and so it’s easy to support policies based on big renewable targets. But they are not enough on their own, or without careful planning and co-ordination at the national level. This requires a broad-based, credible, durable and national climate and energy policy.

Related Analysis

The gas transition: What do gorillas have to do with it?

The gas transition poses an unavoidable challenge: what to do with the potential for billions of dollars of stranded assets. Current approaches, such as accelerated depreciation, are fixes that Professorial Fellow at Monash University and energy expert Ron Ben-David argues will risk triggering both political and financial crises. He has put forward a novel, market-based solution that he claims can transform the regulated asset base (RAB) into a manageable financial obligation. We take a look and examine the issue.

Australia’s Sustainable Finance Taxonomy: Solving problems or creating new ones?

Last Tuesday, the Australian Sustainable Finance Institute (ASFI) released the Australian Sustainable Finance Taxonomy – a voluntary framework that financiers and investors can use to ensure economic activity they are investing capital in is consistent with a 1.5°C trajectory. One of the trickier aspects of the Taxonomy was whether to classify gas-powered generation, a fossil fuel energy source, as a “transition” activity to support net-zero. The final Taxonomy opted against this. Here we take a look at how ASFI came to this decision, and the pragmatism of it.

What’s behind the bill? Unpacking the cost components of household electricity bills

With ongoing scrutiny of household energy costs and more recently retail costs, it is timely to revisit the structure of electricity bills and the cost components that drive them. While price trends often attract public attention, the composition of a bill reflects a mix of wholesale market outcomes, regulated network charges, environmental policy costs, and retailer operating expenses. Understanding what goes into an energy bill helps make sense of why prices vary between regions and how default and market offers are set. We break down the main cost components of a typical residential electricity bill and look at how customers can use comparison tools to check if they’re on the right plan.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.