International electricity prices: How does Australia compare?

Australian retail household electricity prices in the National Electricity Market (NEM) are the lowest they have been for eight years, and on an international comparison are the 10th lowest of the 38 OECD countries.

The average cost per unit of electricity has fallen to 27 cents/kWh according to the most recent Australian Competition and Consumer National Electricity Market (NEM) data. When compared against other countries using a purchasing power exchange rate, Australian average prices per kilowatt-hour are equivalent to 17.6 US cents (c/kWh), well below the OECD average cost of 24.2 US c/kWh and less than many European countries.

Purchasing power parity (PPP) is used to adjust the data to exchange rate differences and ensures a like-for-like comparison when buying an equivalent good or service across borders, therefore PPP can provide a good indication of affordability by country.

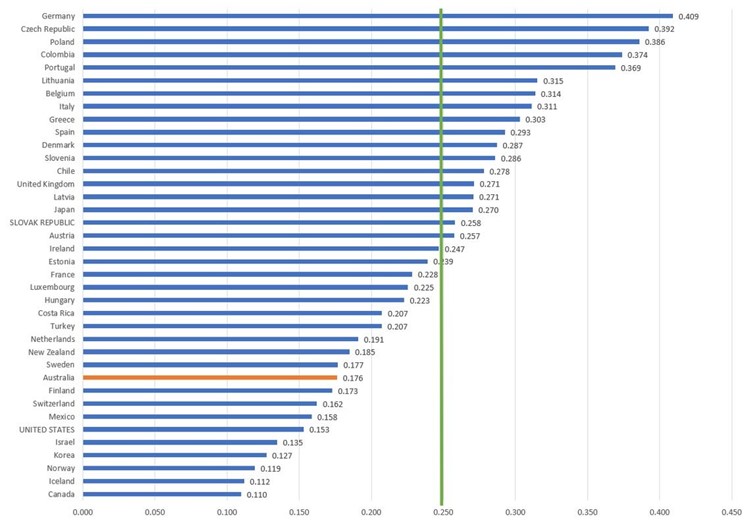

Shown in figure 1, the highest household cost of electricity on a PPP basis is Germany, the Czech Republic, and Poland, while the cheapest residential electricity rates are seen in Canada, Iceland, and Norway.

Figure 1: Household electricity prices - PPP adjusted (USD) *view larger image here

Source: AEC analysis of OECD country data. Green line represents OECD average. Note: The Australian price is based on the ACCC’s average residential price of 27 c/kWh.

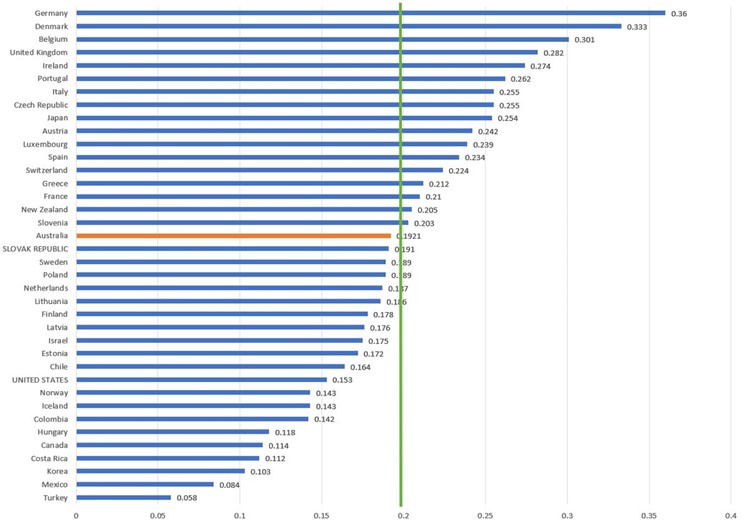

Without the PPP adjustment, Australian residential electricity prices are at 19.21 US c/kWh, just below the OECD average (19.8 US c/kWh, see figure 2).

Figure 2: Household electricity prices OECD (USD) *view larger image here

Source: AEC analysis of OECD country data. Green line represents OECD average.

Australia’s current prices are below what we reported from 2014 when we undertook an international comparison. Then, they were 20.47 US c/kWh (PPP) and lower than the OECD average of 23.03 US c/kWh.

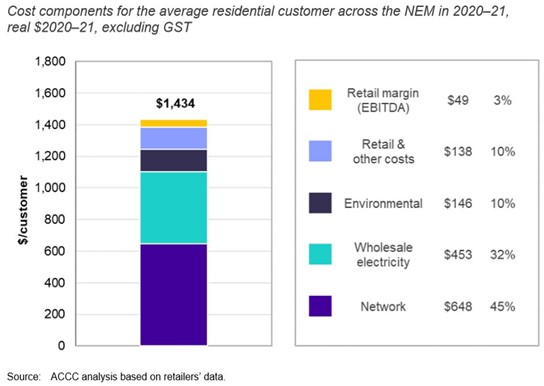

Our latest assessment against international prices is consistent with the ACCC’s most recent findings on prices in the NEM, which were released just before Christmas 2021 and found residential electricity bills were at eight-year lows. The average annual cost of electricity per residential customer in 2020–21 was $1,434, down by $128 (or 8 per cent) compared to 2018–19. All cost components except environmental costs decreased in the last two years, with the largest fall being in wholesale electricity costs (down by $67).

Figure 3: Annual cost to supply an average residential customer

The ACCC noted the cost to supply electricity in the NEM is 32 per cent higher in 2020–21 compared to 2007–08. The electricity inflation index was 63.1 in 2007-08 and 125.7 in 2021. Overall, the Consumer Price Index increased from 89.8 in 2007-08 to 118.8 in 2021.

Figure 4: Electricity and all group CPI Index *view larger image here

Source: AEC analysis of ABS data

Overall customers are seeing the benefits of lower wholesale prices. Wholesale price reductions were the primary driver of costs reductions in the past two financial years, the result of increased renewable generation coming into the system as well as lower fuel costs for coal and gas generation and lower demand due to factors like the impact of COVID on economic activity, milder weather in some areas and growth in household rooftop solar.

Those lower costs are reflected in retail costs over time and as retailers enter new wholesale contracts. Retailer operating costs also fell and retailer margins are at low levels according to the ACCC analysis. The ACCC also notes that over the past seven years network costs have gradually declined.

In contrast the cost of government reforms and environmental schemes are increasing. The cost of the small-scale renewable certificates scheme, which runs through to 2030, has risen reflecting the unprecedented uptake of rooftop solar installations. Environmental costs also include the large-scale renewable energy target, and state-based solar feed-in tariff schemes and renewable targets.

The cost of government reforms were also recently highlighted by increased costs to ACT residents. On 1 July last year, the cost of funding the ACT’s renewable energy target jumped by 133 per cent to $153 million. For an average Canberra household the cost of various 100 per cent renewables policies rose from $176 last year to $423 in this year.

There are some wholesale cost pressures in parts of the NEM beginning to emerge with the market operator pointing to a gap between higher average wholesale prices in Queensland and New South Wales. Factors include increases in underlying traded prices for black coal and gas.

Business prices

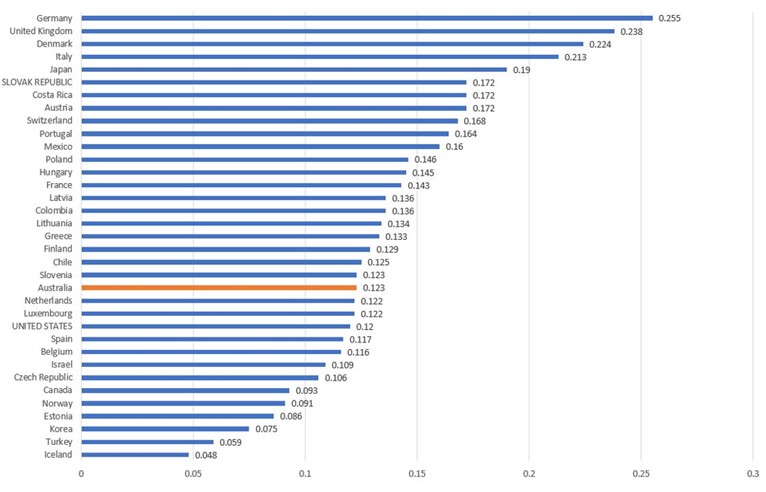

For business customers, OECD data shows Australia ranked 14th lowest out of the 35 member countries reported (figure 5).

This is slightly above costs to US business (12.3 US c/kWh versus 12 US c/kWh), but well below the costs in other major economies such as Germany (25.5 US c/kWh), the United Kingdom (23.8 US c/kWh), Italy (21.3 US c/kWh) and Japan (19 US c/kWh).

Figure 5: Electricity prices – business OECD (USD) *view larger image here

Source: OECD

Top to bottom: International factors

Electricity prices vary from country to country depending on factors like infrastructure costs, government, energy and climate policies, local energy resources and the generation mix.

The highest cost countries for household power bills in our analysis are Germany, the Czech Republic and Poland.

Germany has set an ambitious decarbonisation target for its electricity sector, and more than half of its electricity prices are the result of government-imposed charges including taxes, levies, and surcharges. Its renewable energy surcharge pays a state-guaranteed price for renewable energy to producers and was 6.5 c/kWh in 2021 but is expected to fall to 3.72 c/kWh this year.

The Czech Republic’s generation mix is dominated by fossil fuels, particularly coal. One factor cited for higher prices is the European Commission’s carbon emission reduction plans.

Coal generation is also a major contributor to Poland’s electricity supply; in 2020 power prices increased faster than in any other European Union (EU) country. Poland relies on coal for around 70 per cent of its electricity generation and due to “inefficient production” and EU environmental policies, this has led to a steady rise in the price of electricity in recent years.

European countries have also been contending with higher gas prices pushed up by low stocks and high demand in Asia.

Canada, Iceland, and Norway ranked as the lowest cost countries. Most of lower cost nations are dominated by hydroelectricity plants. Canada sources most of its electricity from hydro (60 per cent), followed by nuclear (13.5 per cent) and gas power plants (11.26 per cent) where it can draw on domestic gas supplies.

Iceland sources its electricity from hydro (73 per cent) and geothermal (27 per cent), while Norway sources nearly all its electricity needs from hydro sources (around 93 per cent).

South Korea, which also has low residential electricity prices, is an exception amongst the lower cost countries. While South Korea is heavily dependent on fossil fuel generation and fuel imports, it also has regulated prices with a fixed-rate and low taxes, which have kept household bills lower. But this may be changing, as the state-owned monopoly Korean Electric Power Corporation increased its rates for the first time in eight years due to the increasing fuel costs from LNG and coal. Flexible electricity rates were adopted and linked to global fuel prices starting in 2021, in a move to improve its profitability.

Related Analysis

Beyond the “loyalty penalty”: unlocking CER value is the real pathway to a services market

The Australian Energy Market Commission pricing review has sparked debate about fairness and competition, with the AEC cautioning against treating price differentials as the core problem. Recent evidence from the ACCC suggests competition and recent reforms are improving customer outcomes with the AEC arguing that a true shift to a services-based market will depend on unlocking and fairly sharing CER value, not weakening the competitive dynamics that drive innovation. We outline our position on the review. Read more.

A New Year: New regulated offer; new records but some old challenges

A new year has brought major developments across Australia’s energy markets, with new regulatory interventions alongside record-breaking renewable generation. The Federal Government’s Solar Sharer Offer marks a significant shift in retail market design, while the wholesale market delivered historic renewable output and much lower prices, driven largely by strong wind and growing battery capacity. We take a look at what these changes mean for customers, retailers and the reliability of the power system, and where old challenges continue to resurface.

2025 Another Year Full of Energy (Developments)

2025 has been another year in which energy-related issues have been front and centre. It ended with a flurry of announcements and releases, including a new Solar Sharer tariff proposed by the Federal Government and the release of the 2026 Integrated System Plan (ISP) draft. Below we highlight some of the more notable developments over the past 12 months.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.