Energy regulation: A tale of increasing overload?

The energy sector is seeing an increase in regulation, with the retail laws and rules seemingly being changed year on year. In 2011, the Gillard Government established the National Energy Retail Laws (NERL) and National Energy Retail Rules (NERR, which “govern the sale and supply of energy from retailers and distributors to customers across the National Energy Market”. Since then, there have been 12 versions of the NERL and 41 versions of the NERR. On top of this, the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) lists 52 retail guidelines, of which 28 are current. A search of the Australian Energy Market Operator’s (AEMO) website for ‘retail procedures’ produces 383 search results.

This captures the dilemma the industry faces - governments and policy makers love to introduce new regulation but have little incentive to remove old, overlapping or obsolete regulation, exacerbating the difficulty in understanding, complying with and enforcing these rules and laws.

As a result, energy regulation is adding to the costs of electricity for customers.

In the past, governments favoured a light-touch regulatory framework that promoted economic efficiency. In recent times, governments have shifted towards a more interventionist framework focused on consumer protection.

While no reputable business doubts the need for appropriate consumer protections, it has created a shift in regulatory attitudes from economic regulator to customer advocate. This shift has dented the focus on a dry but highly important goal to promote economically efficient regulation with the undesirable flow-on effect to customers of higher costs. This is represented through price regulation across the NEM.

Price regulation is justified as a customer protection measure that safeguards customers from high electricity prices. But how true this is in practice, is less clear. Victoria, for example, has seen an increase in customers on the regulated price, which means many Victorian customers are paying more than they would on a market offer. Likewise, the AER’s latest State of the Market Report includes indicators that the number of new retailers in the market is slowing and switching rates have flattened.

Source: AER State of the Energy Market 2023

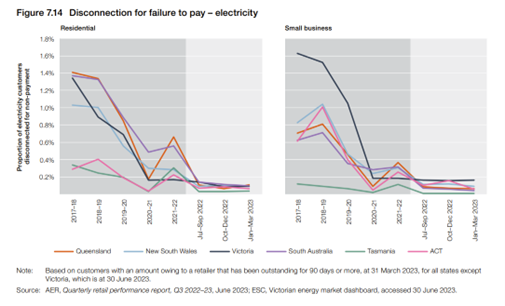

Additionally, the State of the Market report indicates the rate of disconnection remains significantly lower than in pre-COVID-19 years as support like hardship programs become more readily available. This has led to a rise in the number of customers in energy debt across most jurisdictions since mid-2022. Several bodies are seeking to address this through actions focussed on better support for vulnerable customers. For example, retailers and other stakeholders worked closely with the AER to help shape the regulator’s “Game Changer” reforms.

The conclusion from this overview of why the regulation is occurring, is that there is a mixture of well-aimed and targeted reforms, as well as reforms with more questionable merits.

While price regulation has weakened some indicators of retail competition, governments were hopeful another reform – the Consumer Data Right (CDR) – would positively change how customers and businesses interact in the retail market.

The CDR was originally supported because it was seen as a means to give customers better access to their data and was proposed to improve retail competition as it would let customers use their data to make better choices about their energy use, and find energy deals more suited to them, amongst other things. Theoretically the CDR was a reform that could improve the economic efficiency of the market and better protect customers.

Early on, two realities emerged:

1. CDR implementation was going to cost much more than anticipated. The most obvious realization of this was when AEMO conceded the original AEMO Gateway data delivery model was too expensive, and we shifted towards a retailer-led peer-to-peer data access model.

2. Third party stakeholders were lobbying the Government with potential use cases in an effort to expand the CDR’s functionalities, before the CDR framework was even mature.

Even though costs were blowing out, political pressures meant the timelines for energy implementation were left untouched. This brought into question the economic efficiency of the reform.

Meanwhile, at various times throughout various consultations, the Australian Energy Council (AEC) found itself repeatedly cautioning decision makers to consider costs and likely customer uptake when being lobbied about potential use cases:

Even though speculation on the CDR’s future capabilities can be exciting, it must be tempered by an appreciation of the likely consumer uptake and a commitment to upholding strong customer protections. Treasury should bear in mind that data recipients are businesses too and their views on what is best for the customer tend to align with what is best for their business (AEC submission to Treasury)

This comment to Treasury represented a concern the use cases being promoted were not always in the best interests of customers, and more consideration was needed about privacy risks.

While there is always friction between stakeholder interests, some parts of the CDR policy development were particularly challenging. At times, costs were quantified and found to be absurdly high and yet there was no action from policymakers.

This was most obviously the case for the inclusion of large commercial and industrial customers (C&I) in energy, where principled arguments about consistency across sectors and C&I being excluded in banking, were not accepted, as were practical arguments about there being next to no use cases for large energy customers. Then, evidence about the high costs of implementing CDR for C&I customers was collected and presented, only to be ignored. This experience goes back to an earlier point: regulators lack incentives to remove regulation, no matter the cost.

This less than rosy background is given because, other than expending significant resources and costs, the CDR has had next to no impact on customers, with uptake in energy very low.

The policymaker’s defense to this is usually that the CDR is a long-term project, but this begs the obvious question: why did policymakers push a reform where costs were high (much higher than originally expected) and there was no real customer demand?

Although it is a little late for energy, the Government’s decision to pause CDR is a vindication that these concerns were genuine and should hopefully allow the regulatory framework to settle and mature.

Ultimately, it seems CDR was a case where the regulations got ahead of the consumer interest and policymakers arguably may have been speculating about what customers might want. The reality of customer apathy towards the CDR, was just not that interesting.

Customers want energy to be cheap. While the role of economic regulator might be a dry one, it is still important. It is incumbent on businesses, to continue to expect policymakers and regulators to ensure the energy regulatory framework is as efficient as possible, and responds to evidence-based customer concerns, not anecdotes.

Fortunately, there are many examples of retail innovation occurring even despite overregulation of the sector. Often these don’t get the recognition that they deserve.

Retailers take their role as providers of essential services very seriously and the intensive monitoring and reporting of their obligations illustrates this. But these regulatory obligations merely represent a part of their extensive support programs. The willingness of retailers to invest further in supporting customers in need is a sign of their broader customer commitment.

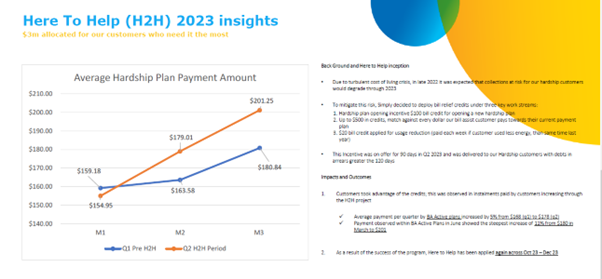

For example, in early 2023, Engie (then Simply Energy) launched a program called 'Here to Help', aimed at helping their customers facing financial pressures by trialling new ways of offering support. Through April and July 2023, over 13,000 customers took up the offer of support, receiving more than $3 million in bill credits. For these customers, the support helped with the impact of price increases, as well as higher winter bills.

Clearly cost of living remains a challenge, so Engie launched the next iteration of Here to Help with payment matching for their Bill Assist customers, along with energy reduction incentives.

And it is not just in the vulnerable customers space where this innovation is happening. There is for example a lot happening around consumer energy resources.

The AGL Virtual Power Plant in South Australia (VPP-SA) project was the first VPP project of its scale announced in Australia in late 2016 and successfully demonstrated that a network of connected energy storage systems could be coordinated to create value across a range of markets. The Australian Energy Market Commission now lists 14 VPPs operating around the NEM.

Tariffs have been in the media lately, but while they focus on the very small minority of customers who have seen their bills increase, they have failed to report on the number of innovative tariffs on offer. For example, Glowbird offers the innovative Free Lunch Energy Plan. This plan offers customers $0.0/kWh electricity between midday and 2pm to encourage electricity use when solar output is high.

Likewise, Powershop offers the Power Drive plan, offering a super off-peak tariff (which varies by distributor) intended to provide cheaper electricity rates from 12am to 4am for EV recharging.

This is just a few examples of some of the innovation which is happening in the retail space. There are many which highlight the many ways in which the competitive market works in the long-term interests of customers. The ongoing challenge for regulators and governments is to ensure that the regulatory environment does not stifle innovation.

Related Analysis

What’s behind the bill? Unpacking the cost components of household electricity bills

With ongoing scrutiny of household energy costs and more recently retail costs, it is timely to revisit the structure of electricity bills and the cost components that drive them. While price trends often attract public attention, the composition of a bill reflects a mix of wholesale market outcomes, regulated network charges, environmental policy costs, and retailer operating expenses. Understanding what goes into an energy bill helps make sense of why prices vary between regions and how default and market offers are set. We break down the main cost components of a typical residential electricity bill and look at how customers can use comparison tools to check if they’re on the right plan.

Principles-based regulations: What are the opportunities and trade-offs?

As Australia’s energy market continues to evolve, so do the approaches to its regulation. With consumers engaging in a wider range of products and services, regulators are exploring a shift from prescriptive, rules-based models to principles-based frameworks. Central to this discussion is the potential introduction of a “consumer duty” for retailers aimed at addressing future risks and supporting better outcomes. We take a closer look at the current consultations underway, unpack what principles-based regulation involves, and consider the opportunities and challenges it may bring.

Regulated Electricity Prices: A look at network and wholesale costs

Retail costs have recently received much attention in the draft regulated Default Market Offer, but network and wholesale costs have also risen. These two components make up the bulk of the final bill, accounting for 33-48 per cent (network) and 31-44 per cent (wholesale) of DMO 7 draft prices. As the energy transition progresses with new network investments and the shift to renewables, storage, and gas, these costs will require closer focus. Last week, we explored retail costs; this week, we examine the network and wholesale cost components.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.