Zero Emissions Dispatchability Discussion Paper

The latest discussion paper in the Australian Energy Council’s series on Australia’s Energy Future focuses on the need for zero emissions dispatchable plant to complement the growth of renewable energy and the retirement of existing coal and gas generation. It also looks at the types of zero emissions dispatchable power currently available.

In considering existing and emerging options for zero emissions dispatchable power the paper addresses the idea that “the sun is shining, or the wind is blowing somewhere” at all times, minimising the need for dispatchable sources. Evidence to date from the National Electricity Market (NEM), it notes, suggests this is not “sufficiently” the case. And in considering correlation between large-scale renewable generation, it finds it is not high enough to avoid the need for firming capacity.

Building renewables out into new areas is unlikely to improve diversity significantly, given the large geographic spread of the NEM, which is one of the largest grids in the world. “Pushing the grid further west, even by hundreds of kilometres, only adds a few minutes of additional solar output in the evening. And wind patterns are large enough that new Renewable Energy Zones (REZs) are unlikely to capture significantly different output profiles,” the paper says.

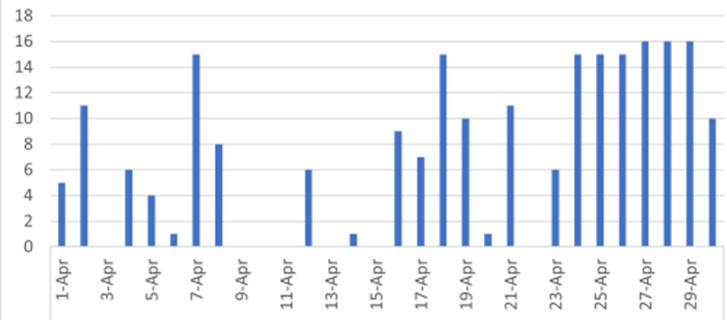

Capacity factors for combined wind and solar in the NEM are rarely above 50 per cent and can dip below 10 per cent. Figure 1 below highlights the number of consecutive hours in April last year with renewable capacity below 15 per cent where there is a need for storage and/or flexible but firm generation.

Figure 1: Consecutive hours of renewables capacity below 15 per cent (2021)

All of this is not an argument against renewables, but rather it highlights that at times we will need dispatchable plant. Dispatchable electricity is likely to be provided by a mix of short duration and long duration storage and plants using low emission fuels.

The realistic options for zero emissions dispatchability fall into two basic types: storage and fuelled plant. The most obvious examples of storage are lithium-ion batteries and pumped hydro. Other potential forms are compressed air, molten salts and flow batteries.

Lithium-ion batteries can deliver 2-4 hours of output but won’t be able to fill bigger gaps in supply. Batteries will play a significant role in meeting short-term supply needs and in providing other services (frequency control and network support) but won’t be the full answer. The NEM and WA’s Wholesale Electricity Market (WEM) will also need long-duration storage, such as pumped hydro, or flexible generation. Equally, demand response can also play a role akin to lithium-ion batteries, but is unlikely to be sustainable for more than a few hours at a time.

Storage, the paper notes, can be categorised by timeframes as well as technology type:

- Distributed storage – behind-the-meter battery installations.

- Coordinated distributed energy resources (DER), which includes the above but which are coordinated (forming virtual power plants). This category can also include EVs with vehicle-to-grid capabilities.

- Medium storage – storage of between 4 and 12 hours, which is useful in intra-day energy shifting.

- Deep storage – storage of more than 12 hours. This is currently delivered by pumped hydro and traditional hydro.

The push to commercialise green hydrogen production and use “presents some optimism” it could provide an additional viable storage source, but it is premature to assume green hydrogen will be economic by 2035. Since green hydrogen is produced using renewable electricity, it is only useful for firming to the extent a long-term storage medium can be developed. Hydrogen-powered plants may also play a role eventually.

While fossil fuel plants are not zero emissions the NEM also includes biomass, waste gas and hydro power plants. Hydro includes run-of-river hydro and dam storage, as well as pumped storage.

Other potential options are technologies that are either not mature or that have specific barriers to deployment in Australia (these include nuclear, tidal/ocean current, and solar thermal) and the paper considers these in an appendix.

You can find the full paper here.

Further discussion papers will be released in coming weeks.

Related Analysis

Nuclear Fusion Deals – Based on reality or a dream?

Last week, Italian energy company ENI announced a $1 billion (USD) purchase of electricity from U.S.-based Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), described as the world’s leading commercial fusion energy company and backed by Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy Ventures. CFS plans to start building its Arc facility in 2027–28, targeting electricity supply to the grid in the early 2030s. Earlier this year, Google also signed a commercial agreement with CFS. These are considered the world’s first commercial fusion-power deals. While they offer optimism for fusion as a clean, abundant energy source, they also recall decades of “breakthrough” announcements that have yet to deliver practical, grid-ready power. The key question remains: how close is fusion to being not only proven, but scalable and commercially viable, and which projects worldwide are shaping its future?

Community Power Network Trial: Potential risks and market impact

Australia leads the world in rooftop solar, yet renters, apartment dwellers and low-income households remain excluded from many of the benefits. Ausgrid’s proposed Community Power Network trial seeks to address this gap by installing and operating shared solar and batteries, with returns redistributed to local customers. While the model could broaden access, it also challenges the long-standing separation between monopoly networks and contestable markets, raising questions about precedent, competitive neutrality, cross-subsidies, and the potential for market distortion. We take a look at the trial’s design, its domestic and international precedents, associated risks and considerations, and the broader implications for the energy market.

Judicial review in environmental law – in the public interest or a public nuisance?

As the Federal Government pursues its productivity agenda, environmental approval processes are under scrutiny. While faster approvals could help, they will remain subject to judicial review. Traditionally, judicial review battles focused on fossil fuel projects, but in recent years it has been used to challenge and delay clean energy developments. This plot twist is complicating efforts to meet 2030 emissions targets and does not look like going away any time soon. Here, we examine the politics of judicial review, its impact on the energy transition, and options for reform.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.