What is “Effective Competition” and do price caps help or hinder?

Energy affordability has been on the radar in Great Britain (GB) in much the same way as in Australia with questions being raised about the benefits of the competitive market and the level of household bills attracting increasing amounts of political attention.

So it’s not surprising that the approach taken in GB has uncanny parallels with Australia – the concerns about affordability led to a major inquiry into the retail market by the competition regulator (the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) in the case of GB, and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission locally), other reviews of the cost of energy and the introduction of price caps for residential customers.

In the case of GB, the price caps were set down in law and imposed from January this year - six months ahead of the default market offer introduced to the National Electricity Market and Victoria’s Default Offer.

The GB caps are only in place until 2023 unless the key government regulator, the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem) recommends to the Secretary of State that they be removed sooner. Ofgem clearly views these price caps as a temporary measure, unlike the default offers in Australia.

The GB price cap on default energy tariffs, including standard variable tariffs (SVTs) covers around 11 million customers (since 1 April 2017 there has also been a cap for prepayment meter energy tariffs which affects around 4 million customers).

Around 53 per cent of residential customers are on default offers, excluding prepayment meter customers, while 49 per cent of GB customers have never switched or have only switched their retailer once[i]. In Australia by comparison six, nine, 14 and 15 per cent of small customers were on standing (or default) offers in Victoria, South Australia, New South Wales and South East Queensland respectively at the end of last year[ii].

Ironically, the GB default price cap started during a period of record switching, increasing market innovation[iii] and falling market concentration. Ofgem’s most recent State of the Energy Market shows that switching rates (or churn) continued to grow 20 per cent in the year to June 2019 up from 19 per cent the year before. They have been increasing since 2014 and, according to Ofgem, the current rates are high compared to other utility sectors and retail energy markets around the world. Previously Norway had the highest European churn rate of 19 per cent, while the highest churn in Australia is in Victoria - according to the Australian Energy Market Operator, 27 per cent of Victorian residential and small business electricity customers switched retailers last financial year[iv].

The question of how to define effective competition is a challenging one that regulators in Australia are yet to grapple with.

“Effective competition”

The question of how to define effective competition is a challenging one that regulators in Australia are yet to grapple with. In contrast, GB’s Domestic Gas and Electricity (Tariff Cap) Act 2018 requires Ofgem to review whether conditions are in place for “effective competition” for domestic supply contracts before it can recommend that the price cap be lifted early. This first review must be published by 31 August 2020 and include a recommendation on whether the cap should remain in place for 2021, or be removed.

So now the regulator has the fraught task of identifying what “effective competition” looks like. It has prompted Ofgem to release a framework[v] that tries to define just that, but has that has raised concerns for highly experienced competition and energy sector experts (more of that below).

In its proposed framework Ofgem has defined effective competition as set out in Figure 1 below along with the conditions that would be in place.

Figure 1: Effective competition – definition and conditions

Source: Ofgem

Source: Ofgem

The framework sets out three conditions that would need to be in place:

- Structural Changes – that are facilitating or can be expected to facilitate the competitive process, including those from government, Ofgem itself and the wider market. It specifically includes progress in the roll-out of smart meters for domestic consumers

- Well-functioning competitive process – there should be no significant barriers to consumers being able to access, assess and act on information on product offerings, there should be commercial opportunity for suppliers to enter the market and strong rivalry across market providers to meet the needs of consumers.

- Fair outcomes for consumers – the market should deliver fair outcomes for consumers in terms of what matters to them, including prices, range of tariffs to suit needs, good quality of service and ease and reliability in switching products.

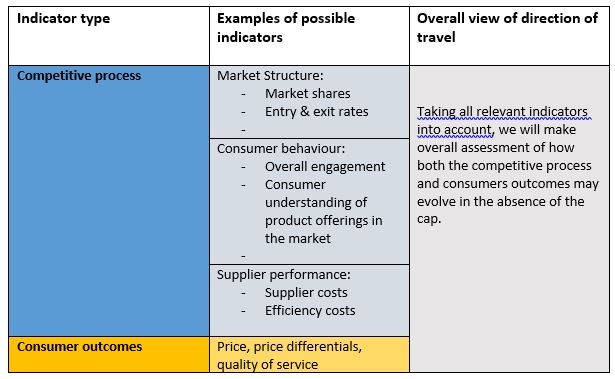

Ofgem has outlined possible indicators to help its assessment of effective competition and these are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Assessment of the conditions for effective competition

Source: Ofgem

To assess whether the conditions have been met, the regulator said it will compare indicators “in the round” and assess the “direction of travel” across the various metrics[vi].

Figure 2 shows the full framework as set out by Ofgem.

Figure 2: Framework for assessing whether conditions are in place for effective competition

Source: Ofgem

Ofgem says it may take time for competition to become effective and that it won’t recommend the caps go unless it is confident the market can deliver “fair outcomes” for consumers and that “we have identified protections that can be implemented in a timely manner for those who, for whatever reason, do not engage in the market”.

Yet in October last year the CMA did not see competition issues when it cleared a proposed merger between SSE (the second largest retailer) and npower (both members of GB’s “Big Six” energy firms) without conditions. This was subsequently called off with the companies citing challenging market conditions, including the number of customer switching provider[vii]. SSE has since proposed a sale to another retailer Ovo. This is subject to regulatory approval.

Red flags

Ofgem’s approach has raised a red flag for several former regulators, among them Professor Stephen Littlechild[viii]. They are concerned that what is being attempted is to design a new concept called “effective competition that embodies socially desirable outcomes, rather than the regulator simply reporting on whether competition would be effective with the removal of a price cap”.

In their response to Ofgem’s initial discussion paper on the framework, the former senior regulators warned that effective competition will not necessarily coincide with a socially desirable outcome or political judgement and rather than “speculate on what effective competition would look like, it would be helpful for Ofgem to identify where it considers competition has not been effective hitherto”.

In their response to the discussion paper, as well as the CMA’s earlier Energy Market Investigation (EMI) Report, it was implied that it is not the case because of factors like a “two-tier” market, excessive price differentials, excessive profit margins, inefficiency and slow adjustment.

“We are not convinced by these suggestions. On the contrary, the competitive market process seems to be working well over time. Competition could be made more effective, not only by removing the tariff cap, but also by removing two present distortions in the regulatory framework. These are associated with exemptions for small suppliers and with compliance procedures for environmental obligations,” the former regulatory heads said.

And they had a message on the best way to help vulnerable customers, stating: “Insofar as it is considered that certain vulnerable customers should have better outcomes, it is for Government to specify which customers, how this is to be brought about and at whose expense.”

Others[ix], such as Energy UK, GB’s energy industry trade association, said that Ofgem’s proposal did not recognise that effective competition delivers different outcomes for different customers, which is a feature of all competitive markets. It also had a concern that if a large number of indicators are being used to determine whether competition is in place it will become extremely tough to conclude whether, “in the round”, the conditions are in place to lift the caps.

While there are customers who find switching difficult, particularly more vulnerable customers, it also argues, there are other ways these customers can be helped and targeted[x].

The state of play

Ofgem’s most recent energy market report shows that 12 suppliers exited the market. It notes that the implementation of the default tariff cap “is unlikely to have triggered these exits, as the suppliers who exited the market had relatively few default tariff customers. Nevertheless, the DTC may affect overall expectations of future revenues and costs associated with running a domestic supply business”.

During the year, medium suppliers expanded, increasing their ability to exert competitive pressure on the GB’s Big Six. “They achieved a net gain as a group of 1.9 million customers, and their combined market share reached above 20 per cent, up by nearly seven percentage points”.

The increased awareness of default tariffs and caps because of increased media exposure may have acted as a prompt for customers to consider switching, based on Ofgem’s assessment.

As with Australia, less engaged consumers tend to be on more expensive tariffs, but the trend over time is for more customers to move away from default tariffs. The proportion of GB customers on these tariffs, which was around 69 per cent in 2015 and gradually fell to 53 per cent by April 2018.

Conclusion

In Great Britain the regulator has been placed in a difficult position – defining what “effective competition” looks like. The assessment will have to balance what may be considered good outcomes for some with not creating too broad a requirement and actually damaging competition. It will also have to manage the fraught political imperatives now at play.

The regulator has suggested that it will determine the “direction of travel”, rather than set thresholds using the empirical data[xi]. Regardless this will not be easy going, but it is certainly going to be fascinating to see how the GB market emerges from this.

[i] https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/publications-and-updates/state-energy-market-2019

[ii] 2019 Retail Energy Competition Review, Final Report, AEMC, 28 June 2019

[iii] Energy Spectrum “The Dark Arts of Removing Price Caps”, July 2019

[iv] Victorian Energy Market Report 2017-18, Essential Services Commission

[v] Framework on conditions for effective competition in domestic supply contracts, Ofgem, 3 October 2019

[vi] Energy Spectrum “The Dark Arts of Removing Price Caps”, July 2019

[vii] https://www.choose.co.uk/news/2019/ovo-energy-buys-sse/

[viii] Response to Ofgem’s Discussion Paper by Stephen Littlechild, Director General of Electricity Supply and Head of the Office of Electricity Regulation (Offer) 1989-1998, Sir Callum McCarthy, Chairman and Chief Executive of Ofgem and the Gas and Electricity Markets Authority (GEMA) 1998-2003, Eileen Marshall CBE, Director of Regulation and Business Affairs, Offer 1989-1994; Chief Economic Adviser and later Deputy Director General of Ofgas 1994-1999; Managing Director, Ofgem and Executive Director, GEMA 1999-2003 Stephen Smith, senior executive positions at Ofgem 1999-2002 and 2003–2010, including Managing Director, Markets, 2004-2007 and Executive Board Member, GEMA 2004-2010, Clare Spottiswoode CBE, Director General of Gas Supply and Head of the Office of Gas Regulation (Ofgas) 1993–1998.

[ix] EnergyUK “Conditions for Effective Competition” 9 July 2019

[x] E-on Submission to Ofgem on developing a framework for assessing whether conditions are in place for effective competition in domestic supply contracts

[xi] Energy Spectrum “The Dark Arts of Removing Price Caps”, July 2019

Related Analysis

What’s behind the bill? Unpacking the cost components of household electricity bills

With ongoing scrutiny of household energy costs and more recently retail costs, it is timely to revisit the structure of electricity bills and the cost components that drive them. While price trends often attract public attention, the composition of a bill reflects a mix of wholesale market outcomes, regulated network charges, environmental policy costs, and retailer operating expenses. Understanding what goes into an energy bill helps make sense of why prices vary between regions and how default and market offers are set. We break down the main cost components of a typical residential electricity bill and look at how customers can use comparison tools to check if they’re on the right plan.

Principles-based regulations: What are the opportunities and trade-offs?

As Australia’s energy market continues to evolve, so do the approaches to its regulation. With consumers engaging in a wider range of products and services, regulators are exploring a shift from prescriptive, rules-based models to principles-based frameworks. Central to this discussion is the potential introduction of a “consumer duty” for retailers aimed at addressing future risks and supporting better outcomes. We take a closer look at the current consultations underway, unpack what principles-based regulation involves, and consider the opportunities and challenges it may bring.

Navigating Energy Consumer Reforms: What is the impact?

Both the Essential Services Commission (ESC) and Australian Energy Market Commission have recently unveiled consultation papers outlining reforms intended to alleviate the financial burden on energy consumers and further strengthen customer protections. These proposals range from bill crediting mechanisms, additional protections for customers on legacy contracts to the removal of additional fees and charges. We take a closer look at the reforms currently under consultation, examining how they might work in practice and the potential impact on consumers.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.