Renewable applications of District Energy

District energy systems are small, localised networks that can utilise waste heat, excess energy from local generation or be connected to the grid to provide heating or cooling. The fundamental idea of district heating is “to use local fuel or heat that would otherwise be wasted, by using a distribution network of pipes as a local marketplace.” [1] It is limited to some rare, niche locations in Australia, but is quite dominant in some countries – particularly those with cold climates and high population density.

Practically, district energy involves a set of pipes being run from a central heating or cooling source underground into homes and businesses. Hot or cold water is deployed into the network to provide heating or cooling, and then returns to be heated or cooled again and again.

District heating has been designed around efficiently capturing waste heat from thermal power stations. But what about when those power stations close in favour of renewable energy – is the district heating system stranded? Developments are emerging overseas that could give these systems a life in even a fully renewable power system. We take a look.

District heating

District heating helps to lower emissions by substituting the normal primary energy supply for home and business heating or cooling. For example, a district heating system may be installed in a residential or industrial area near a coal fired power plant. Waste heat that would otherwise have been exhausted to a lake or cooling tower is pumped from the plant into the district heating system, providing the required heating to homes and businesses.

Additional energy that would have otherwise been needed to provide heating is no longer required, decreasing the emissions generated overall while also driving efficiency.

Historically, district heating systems have operated with pressurised water being pumped out at temperatures above 80 degrees Celsius. Older systems can lose up to 30 per cent or more of their heat before reaching customers premises. Technological improvements over time are leading to the production of more efficient systems, and existing systems are being upgraded. Improvements include better piping insulation and the integration of digitised solutions help to reduce energy loss and allow systems to run at lower temperatures, reducing energy consumption.

District cooling

District cooling involves pumping cool water through distribution pipes to homes and businesses on the network and back to the central cooling plant. After cooling the buildings, the water generally returns with a temperature difference of approximately 10 degrees Celsius higher.

International examples

Northern Europe, China and Russia are responsible for more than 90 per cent of global district heating systems.[2] Sweden has one of the highest penetrations of district heating in the world, with 93 per cent of all dwellings in multi-family residential houses connected to district heating in a 2014 study.[3]

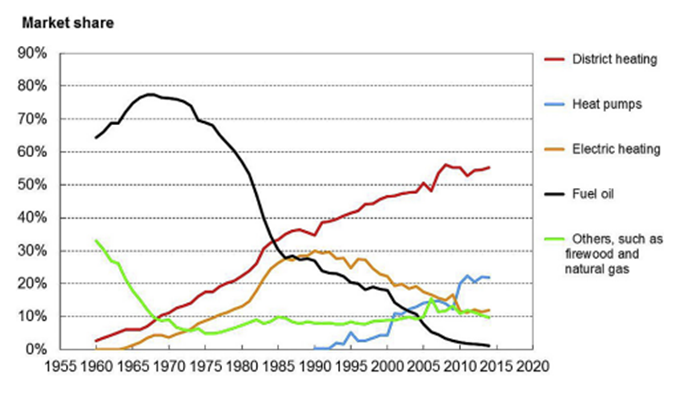

Figure 1: Market shares for heat supply to residential and service sector buildings in Sweden between 1960 and 2014 with respect to heat delivered from various heat sources.

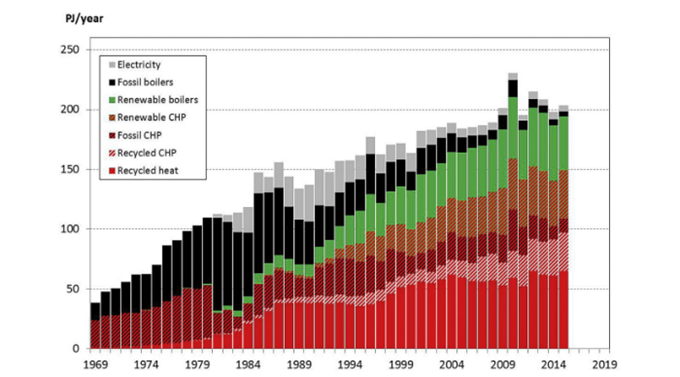

Currently, Sweden’s district heating system is said to provide efficient use of available heat resources through extensive heat distribution with a lower environmental impact and high reliability. Recycled heat supplied into district heating networks comes from a number of sources, including renewable hot water systems and, to a much lesser extent, fossil fuel hot water systems and electrical hot water systems. A breakdown of the heat supplied into Swedish district heating systems between 1969-2015 is provided below.

Figure 2: Heat supplied into Swedish district heating systems 1969-2015

Following the ban on ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFC) as a refrigerant in 1992, Sweden implemented its first district cooling system in Vasteras. As of 2014, more than 40 systems existed in urban areas across Sweden. These draw on natural cold resources (through heat exchanges), absorption chillers, mechanical chillers, (with or without heat recovery) and cold storages.

Australian example

In the late 2000s housing construction in Western Sydney was booming, and property developers started to look for quicker alternatives to connecting to the network to supply electricity and to heat or cool homes. If a gas connection was readily available, developers could install a localised tri-generation system, also known as combined cooling, heating and power.

GridX’s system used on site natural gas-powered generators to supply electricity to the residential development. It also captured generation by-products – excess heat, steam or other gases that would be lost – and deployed them into a local district energy system to heat and cool 16 homes.

District heating using renewable energy

Recently, Finnish start-up Polar Night Energy and Finnish utility Vatajankoski have completed construction on the world’s first sand battery, a high temperature heat storage system. The system is designed to be powered by renewable energy.

The sand battery is designed to draw on excess renewable energy, say on windy days. It also receives waste heat from a data centre it is located next to. The system is able to keep the sand between 500 and 600 degrees Celsius for months. When energy prices increase, the sand battery is called on to heat water, which is then used in the local district heating system.

A similar project, but using water, is under construction in Berlin, Germany. The 200MWh capacity thermal energy storage facility can hold 56 million litres of water. The water will be heated to 98 degrees Celsius when there is excess capacity from wind generation or from waste heat generated in the city. When energy prices are high, the water will be fed into the city’s district heating network and as with the project in Finland, enabling energy that would have otherwise gone to waste to be utilised.

Though not widely deployed in Australia, district energy systems are viable in the right settings and can provide low cost and lower emission heating and cooling solutions for large numbers of people. Internationally they continue to be utilised and new technologies and approaches are emerging to support them.

[1] Werner, District heating and cooling in Sweden, 2017

[2] How does district energy work?, International Energy Agency, 2021

[3] How does district energy work?, International Energy Agency, 2021

Related Analysis

Certificate schemes – good for governments, but what about customers?

Retailer certificate schemes have been growing in popularity in recent years as a policy mechanism to help deliver the energy transition. The report puts forward some recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of these schemes. It also includes a deeper dive into the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme.

The return of Trump: What does it mean for Australia’s 2035 target?

Donald Trump’s decisive election win has given him a mandate to enact sweeping policy changes, including in the energy sector, potentially altering the US’s energy landscape. His proposals, which include halting offshore wind projects, withdrawing the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), could have a knock-on effect across the globe, as countries try to navigate a path towards net zero. So, what are his policies, and what do they mean for Australia’s own emission reduction targets? We take a look.

International Energy Summit: The State of the Global Energy Transition

Australian Energy Council CEO Louisa Kinnear and the Energy Networks Australia CEO and Chair, Dom van den Berg and John Cleland recently attended the International Electricity Summit. Held every 18 months, the Summit brings together leaders from across the globe to share updates on energy markets around the world and the opportunities and challenges being faced as the world collectively transitions to net zero. We take a look at what was discussed.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.