Is Orca a new carbon predator?

The Federal Government has broadened the Australian Renewable Energy Agency’s remit to support technologies to address carbon emissions, including carbon capture and storage, and last week released the agency’s new investment plan.

At the same time a new facility began operating using novel carbon capture technology designed to pull carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere to allow it to be injected underground and turned into a carbonate mineral.

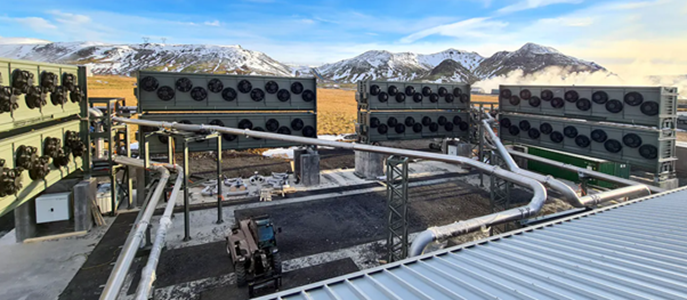

The Orca direct air capture facility in Iceland, was developed by Swiss Group Climeworks, and uses a system of fans, filters and heaters in eight collectors the size of shipping containers to annually draw 4000 tonnes of CO₂ out of the air and trap it (see image below).

Heat piped into the boxes releases the CO₂ from the filters as a pure gas, after which it is combined with water and pumped deep underground where the gas, mixed with water, will slowly become stone as it cools.

Figure 1: Orca direct air capture facility

Source: Climework

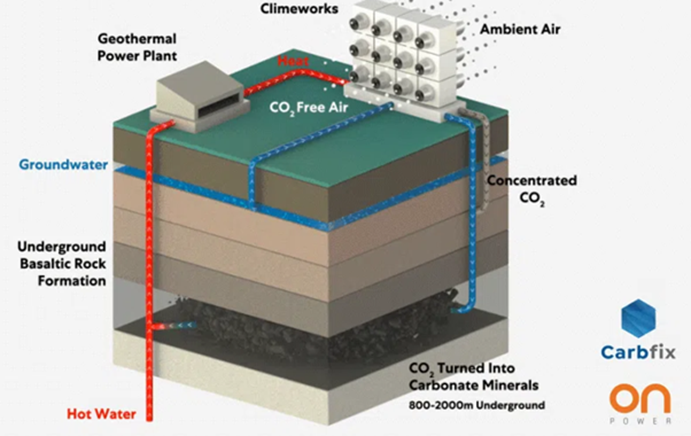

Climeworks entered agreements with Carbfix, a carbon storage start-up, and ON Power, the Icelandic geothermal energy provider, for the project. Iceland was selected because of its geothermal energy supplies and the right underground geology.

The underground storage of CO₂ at the Orca project is undertaken by Carbfix. Carbfix’s process involves “imitating and accelerating a natural process through which dissolved CO₂ and reactive rock formations interact to form thermodynamically stable carbonate minerals, thereby providing a permanent and environmentally benign carbon storage host”.

It began pilot injections in 2012 at the pilot site near ON Power’s Hellisheidi geothermal power plant in south-west Iceland. That earlier pilot showed that most of the CO₂ injected into basalt turned into carbonate minerals in less than two years. Basalt is very favourable for locking up carbon dioxide, according to Juerg Matter, a geochemist who has focused on carbon dioxide capture and storage via in situ mineral carbonation in basalt. For carbon dioxide to transform into carbonate, the rocks where the gas is injected need to have calcium, magnesium or iron-rich silicate minerals. With those, a chemical reaction occurs that converts the carbon dioxide and minerals into a chalky carbonate mineral[i].

The process of drawing carbon dioxide out of the air and pumping it underground demands a significant amount of electricity and heat – so the Orca plant was sited next to the Hellisheidi power plant, which has an installed capacity of 300 MW of electricity and up to 400 MW of thermal energy. The overall process at the Orca plant is shown below.

Figure 2: The Orca plant process

Source: Climeworks

It is not the first plant developed by Climeworks – another direct air capture plant, considered the world’s first commercial facility, was built in Switzerland in 2017, but unlike the Icelandic project it uses the captured gas in greenhouses and sells it to carbonated beverage producers[ii]. That original plant can capture roughly 900 tonnes of carbon dioxide per year. The company has now developed 16 installations across Europe, but the Orca plant is the only one that permanently disposes of the CO₂ rather than recycling it.

Climeworks’ original goal was to capture 1 per cent of annual global CO₂ emissions - more than 300 million tonnes - by 2025, according to Bloomberg. It’s now targeting around 500,000 tonnes by the end of the decade.

As with much new and largely unproven at technology, it is expensive - roughly $800–1084 per tonne of carbon dioxide. Compare that to the current carbon price in Europe, which is approaching AUD$100 a tonne.

Climeworks aims to get the cost down to USD$200 to USD$300 a tonne by 2030, and to USD$100 to USD$200 by the middle of next decade, when it is targeting to have operations at full scale. Only at the lower rate would it become cheaper to use the system than pay a penalty.

In contrast capturing carbon from existing industrial processes with current technology, the cost can be as low as $40 a tonne. That’s because the concentration of CO₂ in those gases can be as high as 10 per cent, rather than 0.04 per cent in the air, according to BloombergNEF.

Apart from Climeworks there are other direct-air capture proponents including US-based Global Thermostat, which abandoned a venture with Exxon Mobil to develop a capable of capturing around 4000 tonnes each year, the same scale as the Orca plant - and Canada’s Carbon Engineering , which is working with Occidental Petroleum to build a plant that can capture around 1 million tonnes of CO₂ from the air annually.

In the race to deal with climate change a range of technologies and approaches are likely to be considered and trialled. Dramatic falls in the price of solar have shown how technological advancements can rapidly change our approach to achieving lower emissions, but many technologies that show early promise can also just as quickly fail to progress.

In the case of Orca it's 4000 tonnes a year of global carbon emissions sorted. Only more than 30,000,000,000 tonnes a year more to get to net zero.

[i] Smithsonian Magazine, June 2016

[ii] Climeworks

Related Analysis

Consumer Energy Resources: The next big thing?

The Consumer Energy Resources Roadmap has just been endorsed by Energy and Climate Change Ministers. It is considered by government to be the next big reform for the energy system and important to achieving the AEMO’s Integrated System Plan (ISP). Energy Minister, Chris Bowen, recognises the key will be “making sure that those consumers who have solar panels or a battery or an electric vehicle are able to get maximum benefit out of it for themselves and also for the grid”. There’s no doubt that will be important; equally there is no doubt that it is not simple to achieve, nor a certainty. With the grid intended to serve customers, not the other way around, customer interests will need to be front and centre as the roadmap is rolled out. We take a look.

Australia’s workforce shortage: A potential obstacle on the road to net zero

Australia is no stranger to ambitious climate policies. In 2022, the Labor party campaigned on transitioning Australia’s grid to 82 per cent renewable energy by 2030, and earlier this year, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese unveiled the Future Made in Australia agenda, a project which aims to create new jobs and opportunities as we move towards a net zero future. While these policies have unveiled a raft of opportunities, they have also highlighted a major problem: a lack of skilled workers. Why is this a problem? We take a closer look.

Made in Australia: The Solar Challenge

While Australia is seeking to support a domestic solar industry through policy measures one constant question is how Australia can hope to compete with China? Australia currently manufactures around one per cent of the solar panels installed across the country. Recent reports and analysis highlight the scale of the challenge in trying to develop homegrown solar manufacturing, as does the example of the US, which has been looking to support its own capabilities while introducing measures to also restrict Chinese imports. We take a look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.