The retail electricity market: Misunderstood or genuinely failing?

The recently released Grattan Institute report ‘Price Shock: Is the retail electricity market failing consumers?[i]’ is an interesting analysis of retailer competition in energy markets, with a particular focus on the retail energy sector in Victoria. Presumably timed to coincide with both the Victorian Government’s Inquiry into Retail Margins and Dr Finkel’s work on a broader national blueprint, it has received some attention across both the media and the energy industry.

It is a truism that energy policy is now highly politicised and sensitive, more so than at any time in the last 50 years. Increasing retail energy prices, occurring against a backdrop of Federal and State government policy uncertainty and commitments to reduce emissions have left most punters confused. There is little clarity about the reasons for higher bills, or any realistic prospect of relief.

As is often the case, the real reasons for retail price rises are many and varied, particularly from jurisdiction to jurisdiction – and for the purposes of this article we have focussed on matters pertinent to the Victorian market. Competition cannot guarantee the lowest possible price for every customer at any point in time, nor can it guarantee that prices will not rise. Governments should similarly be aware that it is not possible to regulate for such an outcome, and efforts to do so may have the perverse effect of enabling more generous profit margins, as shown by the UK’s recent experience.

The misunderstood retailer

The role of the retailer is broader than just a shopfront to sell energy. Like the proverbial duck on a pond, there is much going on below the surface and at any given time retail business are managing the costs and risks of:

- Wholesale energy purchases;

- Renewable energy certificate purchases;

- Bespoke customer protection obligations in Victoria;

- Marketing/acquisition costs, given the high level of switching;

- IT costs (e.g. due to smart meter installation);

- Assisting customers on hardship;

- Credit and bad debt risk;

- Government concessions; and

- Energy efficiency schemes (VEET).

Each retailer, depending on its generation portfolio (if it has one) and risk management practices, deals to these issues differently. Commercial sensitivities prevent the publication (and collection!) of specifics, and this perceived opaqueness has played into the hands of commentators such as the Grattan Institute, which leads to profit margin estimates that suggest retailers are ripping off customers.

Generation changes

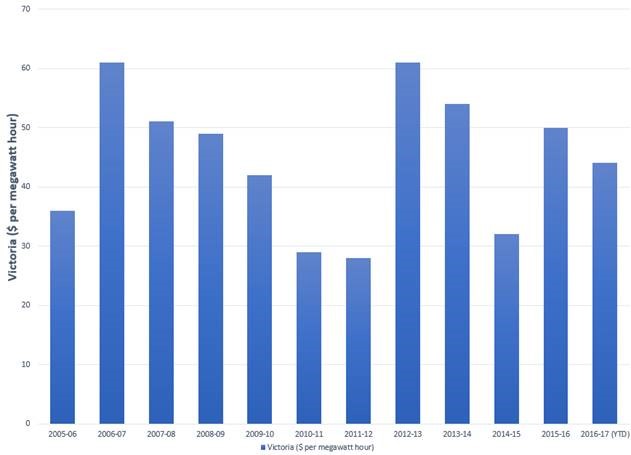

Price increases are also a direct result of major changes in the generation of electricity in Victoria and its impact on the wholesale electricity market, rather than the level of retail competition. Retailers in Victoria manage wholesale risk and stabilise end customer prices. They do this by contracting with suppliers in advance to manage the volatility in wholesale prices. Contrary to the Grattan Institute’s assertion that wholesale prices have been relatively stable in Victoria over the last 10 years (Figure 1.3), the chart below shows the spikes in the annual volume weighted average spot prices over that same period. Of course, wholesale pool prices are volatile and are expected to become more volatile with the closure of the Hazelwood power station.

Figure 1. Annual volume weighted average spot prices 2005-06 to 2016-2017 YTD

Metering and marketing costs

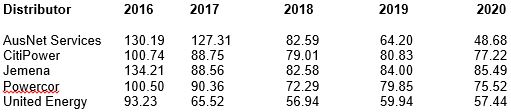

The Grattan Institute also does not take proper account of metering charges in Victoria, which have been a key cost borne by the retail market. Whilst it states that metering charges have been falling since 2014, they are still at a materially high level, as the table below shows (and remain substantially higher than other jurisdictions):

Table 1: annual metering charge, $/household customer

In other jurisdictions, metering has been opened to competition, which gives retailers the ability and incentive to manage this element of the cost stack as well as to differentiate through the capabilities of the meter. But that process has only just started so of course it’s too soon to see how that has worked out in practice.

In a competitive market such as Victoria’s, the costs to retailers to market to present and prospective customers, is understandably substantial. Higher marketing and communications costs are necessary to achieve the benefits of a competitive market, as its participants strive to bring their most attractive opportunities to our attention.

Constraints with policy uncertainty

It’s notable that some of the features of the retail market that are the cause of concern have their basis in government regulations and prohibitions. The practice of discounting from a standing offer is predicated on the requirement to make a standing offer. The practice of pay-on-time discounts is in part a response to bans on late payment charges.

The report does not fully consider that regulation and ongoing government policy intervention (State/Federal) may continue to be a key constraint on retailers’ incentive to diversify their service offerings.

The Grattan Institute does acknowledge the fact that there are additional regulatory measures in place in the Victorian market which present challenges. These peculiarities make it generally more expensive for retailers to do business there. For example, Victoria has been particularly affected by a range of different regulator-driven cost changes that are split between 1 July and 1 January. Other jurisdictions are nearly all focussed on 1 July changes, which makes it easier for retailers to manage costs risks across each financial year. There’s still a lot of risk in offering multi-year fixed price details, which might otherwise be attractive to customers and create the potential for a longer-tem relationship (e.g. to assist with energy efficiency, etc.). Retailers may be wary given recent history on the rate of change of annual network tariffs, plus escalation in REC requirements, amongst other things.

Governments’ ability and propensity to add costs through schemes and taxes is a further risk factor, and the way that governments do this influences tariff design. So because Renewable Energy Certificatess and VEET certificates are payable on a volume (MWh/KWh) basis, the risks entailed in offering a fixed “all-you-can eat” price are greater, which may explain why it’s only recently that such offers have begun to emerge. This is also affected by tariff design, which was historically KWh driven, although now demand tariffs are available, such deals may become more widely offered.

Customers engage with competitive markets differently

Competitive markets cannot be expected to deliver the lowest price to every customer every day. Price dispersion is a sign of a healthy competitive market, and government policy should be directed to ensuring that there are no barriers to customer engagement with the market, and that the most vulnerable customers are given specific support to ensure that they receive the most competitive deal appropriate to their circumstances.

This is already occurring. Retailers in every jurisdiction are regulated with regard to their treatment of hardship customers. In Victoria for example the Energy Retail Code obliges a retailer to offer to move customers who are experiencing financial stress to their most competitive market offers. Retailers are also obliged in Victoria to inform customers when favourable market tariff rates cease and their contract moves to a less advantageous market tariff, or a standing offer.

Just as market offers are complex, so are customers. There is no universal customer. As with their phone bills and plane tickets, customers have a broad spectrum of engagement preferences. Some are not price sensitive and value no engagement with their retailer as preferable to shopping around for the best deal. Others are highly engaged, because of financial concerns or an interest in extracting the best value deal available.

The Report interprets declining switching rates as indicative of poorer outcomes for customers. On the contrary, low switching rates can indicate that retailers are doing the necessary work to retain their customers. Anecdotally we know that some retailers will extend customer contracts at the same market discount as originally offered. Low switching rates can also indicate that a customer would prefer not to engage on the subject of their energy costs. This may not be the fault of the market, but can also be because a customer has decided that this is their preference.

It is regulators’ role to ensure that there are no unreasonable barriers to the engagement of customers with the retail energy market, not to make choices regarding what is best for each customer.

Conclusion

Retail electricity has relatively low barriers to entry and exit (as can be seen by the number of new entrants to the market) but we don’t see major retail brands like supermarkets or other service providers in the market. This suggests they do not see sufficiently high margins to enter it. If they could really earn twice as much margin as in their existing markets, wouldn’t the opportunity be too great to pass up for these large businesses with sophisticated marketing techniques and extensive customer databases?

By its own admission the interventions contemplated by the Grattan Report such as increased monitoring of prices, simplification of tariff offers and re-regulation “may not reduce electricity costs.” This was certainly the experience of the UK regulator, Ofgem which in 2013 intervened in the market to deal with perceived issues around discounting and complexity. The tangible result of this intervention was not to the benefit of consumers, rather retailers enjoyed even greater profits on the back of their standing offer customers[ii]. Ofgem’s preference now, sensibly, is on better customer engagement and communication.

The Grattan report opines that retailers’ profit margins are excessive. However it does not factor in sufficiently the difficulties faced by retailers in estimating future wholesale energy costs and the load they will have to supply each half-hour of the year, and managing the risk of getting it wrong. Invariably the cost of managing wholesale market risk is material, compared to a consultant who can assess actual wholesale costs with the benefit of perfect hindsight.

The opacity of what prices are on average (given the wide variation between the cheapest and the dearest offers of many retailers) and of margins does not make for a very well-informed debate. It is not the norm across other industries for margins and cost structures to be made transparent.

The AEC supports the report’s assertions that the retail market is complex, and often misunderstood. However, the AEC would caution policymakers against rash decisions here. The energy market should be subject to robust scrutiny, whilst noting that is very much still in its infancy. It has a way to go in terms of delivering on the promises of economic efficiency principles. But any measures by which government might seek to control retailers’ behaviour, should be weighed up against the actual value of such intervention to consumers.

[i] Grattan Institute, ‘Price Shock: Is the retail electricity market failing consumers?’ https://grattan.edu.au/report/price-shock/

[ii] http://www.eprg.group.cam.ac.uk/report-regulation-of-retail-energy-markets-in-the-uk-and-australia-by-s-littlechild/

Related Analysis

What’s behind the bill? Unpacking the cost components of household electricity bills

With ongoing scrutiny of household energy costs and more recently retail costs, it is timely to revisit the structure of electricity bills and the cost components that drive them. While price trends often attract public attention, the composition of a bill reflects a mix of wholesale market outcomes, regulated network charges, environmental policy costs, and retailer operating expenses. Understanding what goes into an energy bill helps make sense of why prices vary between regions and how default and market offers are set. We break down the main cost components of a typical residential electricity bill and look at how customers can use comparison tools to check if they’re on the right plan.

Principles-based regulations: What are the opportunities and trade-offs?

As Australia’s energy market continues to evolve, so do the approaches to its regulation. With consumers engaging in a wider range of products and services, regulators are exploring a shift from prescriptive, rules-based models to principles-based frameworks. Central to this discussion is the potential introduction of a “consumer duty” for retailers aimed at addressing future risks and supporting better outcomes. We take a closer look at the current consultations underway, unpack what principles-based regulation involves, and consider the opportunities and challenges it may bring.

Navigating Energy Consumer Reforms: What is the impact?

Both the Essential Services Commission (ESC) and Australian Energy Market Commission have recently unveiled consultation papers outlining reforms intended to alleviate the financial burden on energy consumers and further strengthen customer protections. These proposals range from bill crediting mechanisms, additional protections for customers on legacy contracts to the removal of additional fees and charges. We take a closer look at the reforms currently under consultation, examining how they might work in practice and the potential impact on consumers.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.