The ups and downs of energy policy

With the most recent Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Energy council meeting and former Vice President Al Gore’s visit to Melbourne to speak with state ministers, a spotlight has again been thrown on the possibility of states going it alone on energy policy without national agreement on a clean energy target.

South Australia, Queensland, Victoria and the ACT used a meeting with the former Vice President to begin discussions about creating their own state-based clean energy target. South Australia, Queensland, Victoria, ACT and New South Wales are also pursuing net zero emissions targets by 2050.

With the Federal Government still not committing to adopting Chief Scientist Alan Finkel’s recommendation of a nationwide clean energy target, the states’ frustration is understandable. However, as pointed out by the Productivity Commission in regards to recent statements of government funded storage projects such as the South Australian battery, there is a risk that governments going it alone and intervening in the market “will lead to the wrong infrastructure in the wrong place and the electricity consumer will end up paying higher prices as a result”. They point out that, given this risk, any investment decisions should be delayed until the government responds to the Finkel review and implements a mechanism to meet Australia’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions targets.

The need for a nationally coordinated policy has been echoed in the Finkel report. “The Panel recommends that the COAG Energy Council endorse a national strategic energy plan for the NEM informed by the Blueprint in this report”. There is a resounding call for coordinated national climate policy. In the face of the current policy vacuum at the federal level, the states are proposing their own mechanisms to meet emissions targets and provide energy security.

COAG’s Energy Council was established with these broad themes:

- Overarching responsibility and policy leadership for Australian gas and electricity markets

- Promotion of energy efficiency and energy productivity in Australia.

- Australian electricity, gas and petroleum product energy security.

- Cooperation between Commonwealth, state and territory governments.

- Facilitating the economic and competitive development of Australia’s mineral and energy resources[i].

Over at least the past decade jurisdictions have sought to push policies to reduce emissions from the electricity sector, but it has led to the policy hodge podge we are currently dealing with in the National Electricity Market (NEM) and less efficient outcomes that in turn may need to be addressed. Recent modelling by Frontier Economics suggested that Australia could meet its Paris commitment of 26-28% reduction in emissions by 2030 even in the absence of a federal policy, based on the states’ current commitments.[ii] But this does not mean that it would be an efficient way to do so. Issues arise where the states effectively enter an “arms race” – the rush to offer the best solar feed in tariffs by jurisdictions to encourage the uptake of solar PV is a prime example. We are seeing elements of this with state-based renewable targets. Below we take a look at the some of the state-based schemes and the stop-start nature of the policy initiatives over the years.

Emission reduction schemes

The idea of states having their own broad ranging market based emissions reductions schemes has been seen before. New South Wales commenced their Greenhouse Gas Reduction Scheme (GGAS) at the beginning of 2003 and is quoted by the Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal as being the first GHG emissions trading scheme in the world.[iii] The scheme obliged all New South Wales electricity retailers to reduce a portion of the GHG emissions attributable to their sales/consumption of electricity in the state. Greenhouse gas abatement certificates were created by accredited providers for reducing emissions from existing generators, producing electricity from low emissions technologies, improving energy efficiency, sequestering carbon in forests and reducing emissions from industrial processes. This scheme closed on 1 July 2012 to avoid duplication with the federal carbon tax which was introduced and later withdrawn.

Gas Development Scheme

Queensland introduced a gas scheme in 2005 in order to reduce emissions and encourage gas development in the state. It was initially driven by the Beattie Government’s policy – A Cleaner Energy Strategy, which mandated that by 2005, 13 per cent of the state’s electricity should come from gas power stations. This scheme was also closed in 2013 following the federal carbon pricing mechanism. As the ‘carbon tax’ would provide an advantage to gas over coal, the scheme was no longer seen to be needed.

Feed in tariffs (FiT)

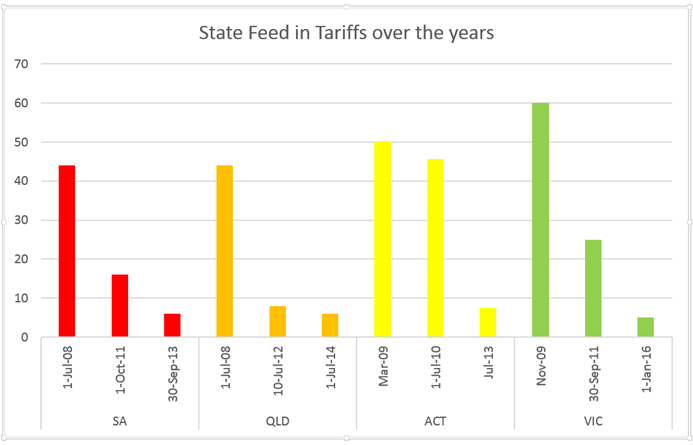

The states began implementing solar feed in tariffs in 2008. It quickly began somewhat of an arms race as states began announcing ever more generous schemes. As shown below, all were drastically reduced a few years later due to unprecedented popularity and the strain it places on state budgets. Now some states have no mandated minimum FiT and allow retailers to choose what level to set them at.

Figure 1: State solar feed in tariffs 2008-2016

Source: State government websites

Renewable energy targets

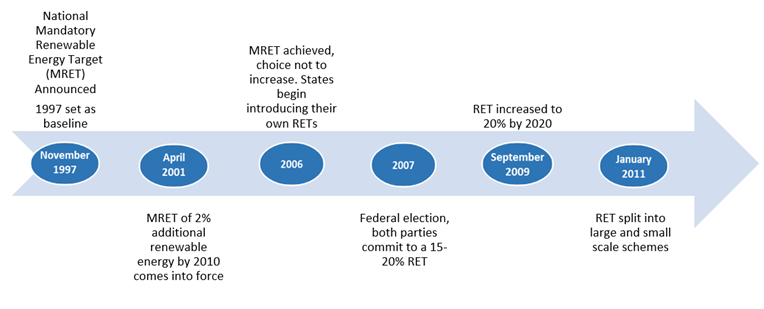

Australia introduced a Mandatory Renewable Energy Target (MRET) in 2001 to achieve an additional 2 per cent renewable energy by 2010. At the time, South Australia encouraged developers to establish wind farms in the state to meet the target. The MRET was assessed in 2003 and the Tambling Review recommended that the target be extended to 2020 and be set at 20,000GWh - a recommendation the Federal Government did not accept.

The subsequent Rudd Labor Government introduced a RET in 2009 with a 20 per cent target – effectively 41,000 GWh target in 2009. That target in turn was amended with the passage of the Renewable Energy (Electricity) Amendment Bill 2015 in June 2015. As part of the change the Large-scale Renewable Energy Target was reduced to 33 000 GWh in 2020 – effectively 23.5 per cent by 2020.

Figure 2: Federal renewable energy target timeline

Source: Climate Council

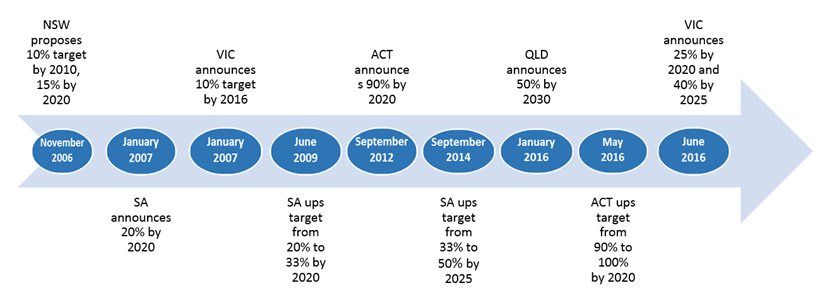

Following the earlier federal decision not to increase the MRET in 2006, state governments began introducing their own more ambitious targets. New South Wales began with their proposal, with South Australia and Victoria following with their targets, see figure 3 below. The 2007 Victorian renewable energy target was subsequently subsumed into the national scheme when it was expanded in 2009[iv]. Since New South Wales and Tasmania have not implemented their own scheme, they fall back on the national target of 23.5 per cent by 2020, although New South Wales has committed to zero net carbon emissions by 2050.

Figure 3: State based renewable energy targets since 2006

Source: State government websites

Energy Efficiency Schemes

Just like other policies, most of the NEM states have also implemented energy efficiency schemes, following is a summary of the various states efforts.

NSW: Energy Savings Scheme (ESS) places a mandatory obligation on scheme participants to obtain and surrender energy savings certificates which are generated by the installation of efficiency measures.[v]

VIC: Energy Efficiency Target (VEET) places a liability on large energy retailers in Victoria to surrender a specified number of energy efficiency certificates every year. Certificates are created when accredited entities help energy consumers make energy efficiency improvements to their homes, businesses or non-residential premises. [vi]

SA: Retailer Energy Efficiency Scheme (REES) requires obliged energy retailers to meet annual energy efficiency and energy audit targets. Retailers then offer incentives for customers to install energy efficiency improvements.[vii]

ACT: Energy efficiency improvement scheme (EEIS) is compulsory for electricity retailers. Requirements are placed on electricity retailers to achieve energy savings in households and small-to-medium businesses.[viii]

Conclusions

The frustration of state governments with the current federal climate policy vacuum is understandable, but state-based mechanisms have tended to complicate the energy market. What is really needed is stable, coordinated national policy. The risk for the National Energy Market (NEM) if a national policy cannot be reached is that the states will continue to implement their own schemes. With a highly interconnected system such as the NEM, it makes little sense to have disjointed policy regarding electricity emissions on a state by state basis. .

[i] http://www.coagenergycouncil.gov.au/about-us/our-role

[ii] http://www.frontier-economics.com.au/documents/2014/09/can-australia-still-meet-emissions-target-changes-ret.pdf

[iii] https://www.ipart.nsw.gov.au/Home/Industries/Energy/Energy-Savings-Scheme/Greenhouse-Gas-Reduction-Scheme

[iv] http://climatechangeauthority.gov.au/files/DiscussionPaper-RET-Review-20121031.pdf

[v] http://www.ess.nsw.gov.au/How_the_scheme_works/Scheme_Performance/Certificate_market

[vi] https://www.veet.vic.gov.au/Public/Public.aspx?id=Home

[vii] http://www.escosa.sa.gov.au/industry/rees/overview/rees-overview

[viii] http://www.environment.act.gov.au/energy/smarter-use-of-energy/energy_efficiency_improvement_scheme_eeis

Related Analysis

Climate and energy: What do the next three years hold?

With Labor being returned to Government for a second term, this time with an increased majority, the next three years will represent a litmus test for how Australia is tracking to meet its signature 2030 targets of 43 per cent emissions reduction and 82 per cent renewable generation, and not to mention, the looming 2035 target. With significant obstacles laying ahead, the Government will need to hit the ground running. We take a look at some of the key projections and checkpoints throughout the next term.

Certificate schemes – good for governments, but what about customers?

Retailer certificate schemes have been growing in popularity in recent years as a policy mechanism to help deliver the energy transition. The report puts forward some recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of these schemes. It also includes a deeper dive into the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme.

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.