Targets, targets everywhere, but what’s the plan?

Australia’s states are, to varying degrees, setting targets and policies to increase investment in renewable energy and maximise investment locally in the sector. The Queensland government has a 2030 renewable energy target of 50 per cent, the Victorian government has a target of 40 per cent by 2025 and the ACT aims to be 100 per cent renewable by 2020.

Wholesale electricity markets are highly complex and government-led market interventions have substantial consequences when aggregated across the National Electricity Market (NEM). The transition to a lower emissions economy is not costless, and the costs and benefits should be clearly articulated to consumers who will be required to support the cost of the various government renewable and environmentally-friendly schemes. This article examines options to better manage energy markets with high levels of intermittent generation.

Reverse auctions are rising in popularity as a tool to deliver government programs and reverse auctions were used by the ACT Government for its renewable energy scheme[i]. In September 2016, Intelligent Energy Systems (IES) released findings of modelling of a 50 per cent renewable energy target by 2030 achieved with reverse auctions[ii]. They found that a NEM-wide target achieves greater benefits than local policies by taking advantage of a wider diversity of renewable energy resources. The results also show that dispatchable generation plays an essential role in meeting demand when wind and solar are not available. The findings echo those made by the Climate Change Authority that state-based target policies will assist Australia to meet its emissions reduction objectives, but could also result in uneven investment incentives across jurisdictions, increasing the overall cost of meeting those objectives[iii].

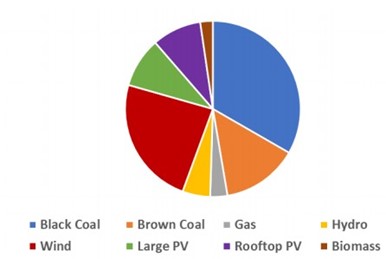

The IES results show that in 2030 the target would be met by new wind turbines and large photovoltaic (PV) installations (Figure 1). The 50 per cent target scenario was estimated to reduce NEM emissions by 41 per cent when compared to 2005 levels.

Figure 1: Intelligent Energy Systems modelled generation in 2030, under a 50 per cent renewable target scenario

Source: Intelligent Energy Systems, 2016

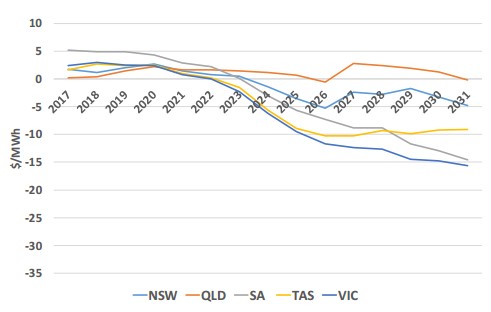

The IES modelling results show that wholesale prices rise in the short term to 2022, then decline to 2030. The contract for difference payments levied on consumers mean that most of this benefit is repaid through the renewable energy scheme. Figure 2 shows the changes to retail prices under the renewable energy target, where contract-for-difference payments are incorporated into consumers’ retail bills.

Figure 2: Retail price impacts by region (curtailment costs are not passed through)

Source: Intelligent Energy Systems, 2016

The estimated benefits of the transformation are somewhat offset by the costs. The direct costs of the contract for difference payments are included in the chart above, but other costs were not included such as curtailment costs or the cost of additional ancillary services. IES found that during the middle of the day there was surplus energy generated and wholesale prices were very low (averaging $5 MWh), resulting in curtailment of wind and solar generation. In 2030 the estimated curtailment was over 20 TWh or around 11 per cent of total generation[iv]. The lost revenue to renewables as a result of curtailment was calculated to be $1.8 billion in 2031. Once curtailment costs are incorporated into retail prices, consumers would be worse off under the target scenario in NSW and Queensland.

The results show that this policy does not achieve efficient emissions abatement. A subdued demand outlook meant that black coal generators may be retired from service before brown coal generators, which is counter to the objective of increasing renewables to reduce emissions. IES conclude that the 50 per cent renewable target is unlikely to be sending the most efficient carbon abatement signal to the market. The IES analysis did not consider power system security or reliability or the long term viability of the wholesale market under policy uncertainty, but others have considered these issues.

The "Pressure cooker" effect

In September 2016, the Energy Policy Institute of Australia (EPIA) published analysis on the limitations of intermittent renewables in energy markets[v]. EPIA found that increasing intermittent generation in a power system has a “pressure cooker” effect and can result in unaffordably high integration costs at high shares of intermittent generation. The EPIA found that while every power system is inherently different, in most systems, the practical upper limit for renewables is around 40 per cent of total electricity generated. The EPIA base this estimate on a review of over 100 published studies which found that high shares of 30-40 per cent of wind can lead to integration costs of up to 50 per cent of generation costs[vi]. Power systems can operate with shares of intermittent generation well above the estimate of 40 per cent, but it is likely to require increasing levels of support and lower utilisation which adds to the costs. The research suggests that the rate of support as intermittent generation becomes a larger share of a system increases, rather than being linear in a "pressure cooker" effect. Support for high shares of intermittent generation includes:

- interconnection with adjoining power systems; and

- more energy storage; and

- ancillary services for system security and reliability; and

- increased demand-side management; and

- regulatory changes.

As discussed in the IES analysis, curtailment of intermittent generation can add to the cost of producing electricity. Lower utilisation of capital-intensive conventional generators increases their average cost. And intermittent renewable generators grounding production or switching down during low demand lowers their utilisation. Both of these effects lower the capital productivity of energy generation.

Investment in network upgrades to provide additional ancillary services or to import energy when intermittent generators are not producing also increases the total cost of intermittent generation. Comparable high-renewable regions around the world such as Texas and Denmark rely heavily on interconnection with other regions to balance and support intermittent generation.

The EPIA find that as conventional generation is displaced, the need for support services provided by these generators increases. Solar and wind generators do not currently provide ancillary services to AEMO. However, AEMO is investigating ways in which additional infrastructure added to wind facilities might assist with these services in the future[vii]. The scale-up of intermittent generation can diminish the system strength of parts of the power system as synchronous generators leave the system. For example, in Tasmania new wind farms have installed synchronous condensers to strengthen their connection with the network. The EPIA believe that this can also magnify the short and long-term risk of investing in non-renewable generation assets and the power grid itself.

Regulatory changes

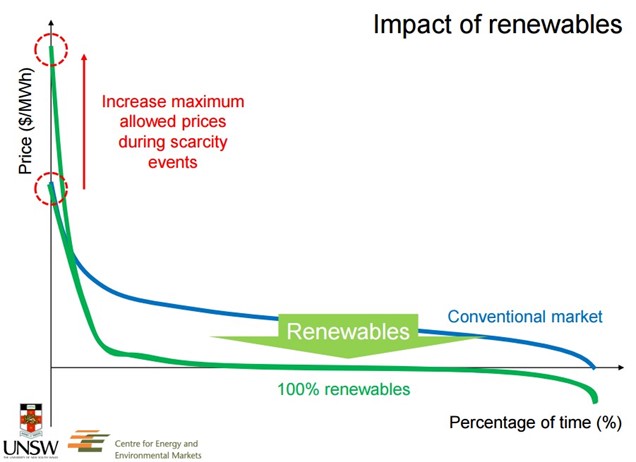

One option investigated with analysis from Australia’s NEM is reforming the market price cap (or maximum wholesale price allowed). Most of the time, the least-cost dispatch process in place in Australia’s electricity markets mean that generators receive the price to cover their short run marginal costs. Energy-only markets experience high price volatility because short periods of extreme prices are necessary for generators to recover their fixed costs over the long term. A maximum price cap is set to protect energy consumers from very extreme prices. Research has shown that under a scenario of 100 per cent renewable energy, the market price cap of the NEM may need to rise to between $60,000 and $80,000 MWh[viii]. The price cap (maximum price) is currently set under $14,000 MWh. Figure 3 shows that a high share of intermittent generation lowers price received for a large proportion of time in a year. But for a small share of time each year, the maximum price increases when renewables are not producing.

Figure 3: NEM wholesale prices under high renewables, higher peak price events[ix]

Source: Riesz J, 2015

An increase to the market price cap would have the benefit of ensuring revenue earned at high price periods signals a need for new investment. Higher price caps may ensure new generation enters the market when it is needed. However, the higher maximum price would likely lead retailers to rely more heavily on contracts to hedge their risk in the market, increasing the average price of futures contracts.

The IES, EPIA as well as ongoing work by AEMO show that Australia can achieve a high renewable energy target however, the full cost of the transition is likely to be more than the cost of the technology itself. The impact of intermittent renewables on power system security and costs varies with the characteristics of the power system, the flexibility of generation, the level of complementary interconnection and the regulatory requirements governing the market.

[i] ACT Environment and Planning Directorate, 2016, http://www.environment.act.gov.au/energy/cleaner-energy/how-do-the-acts-renewable-energy-reverse-auctions-work

[ii] IES, 2016, Can the National Electricity Market achieve 50% renewables?, Insider paper 24, http://iesys.com/assets/news/attachments/Insider-024.pdf

[iii] Climate Change Authority, 2016, Towards a climate policy toolkit; Special Review on Australia’s climate goals and policies, http://climatechangeauthority.gov.au/sites/prod.climatechangeauthority.gov.au/files/files/Special%20review%20Report%203/Climate%20Change%20Authority%20Special%20Review%20Report%20Three.pdf

[iv] IES estimate 8.6TWh of utility scale solar PV and 11.6 TWh of wind generation are curtailed in 2030, and AEMO forecast consumption to 2030-31 to remain flat at around 185 TWh.

AEMO, 2016, National electricity forecasting report, http://www.aemo.com.au/Electricity/National-Electricity-Market-NEM/~/-/media/080A47DA86C04BE0AF93812A548F722E.ashx

[v] Energy Policy Institute of Australia, 2016, the “pressure cooker” effect of intermittent renewable generation in power systems, Paper 6/2016, http://energypolicyinstitute.com.au/images/6_Simon_Bartlett.pdf

[vi] Hirth, Lion, Falko Ueckerdt & Ottmar Edenhofer (2015): “Integration Costs Revisited – An

economic framework of wind and solar variability”, Renewable Energy 74, 925–939

[vii] Australian Energy Market Operator, 2016, Future power system security review, https://www.aemo.com.au/Electricity/National-Electricity-Market-NEM/Security-and-reliability/FPSSP-Reports-and-Analysis

[viii] Riesz, J., Gilmore, J. and MacGill, I., 2016, Assessing the viability of Energy-Only Markets with 100% Renewables, Economics of Energy & Environmental Policy, 5(1)

[ix] Riesz, J., 29 May 2015, presentation, Center for Energy and Environment Markets UNSW, http://ceem.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/event/documents/Riesz-EOM%20with%20high%20renewables-2015-05-29b.pdf

Related Analysis

Climate and energy: What do the next three years hold?

With Labor being returned to Government for a second term, this time with an increased majority, the next three years will represent a litmus test for how Australia is tracking to meet its signature 2030 targets of 43 per cent emissions reduction and 82 per cent renewable generation, and not to mention, the looming 2035 target. With significant obstacles laying ahead, the Government will need to hit the ground running. We take a look at some of the key projections and checkpoints throughout the next term.

Certificate schemes – good for governments, but what about customers?

Retailer certificate schemes have been growing in popularity in recent years as a policy mechanism to help deliver the energy transition. The report puts forward some recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of these schemes. It also includes a deeper dive into the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme.

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.