Reforming the Safeguard Mechanism: The opportunities and challenges

The ALP’s policy platform includes a promise to reform the Safeguard Mechanism to drive carbon abatement in industrial emissions. This is a sector where emissions are projected to increase so reversing this trend is paramount if Australia wishes to achieve its ambition of being net-zero across the economy, rather than only in electricity.

Here we take a deep dive into what we know about the ALP policy, and what unknowns lay ahead in its implementation.

Efficacy of the Safeguard Mechanism

The Safeguard Mechanism commenced in 2016, following the Abbott Government’s abolition of the carbon price and introduction of its Direct Action policy. It was framed as a less punitive way to cap emissions by requiring each industry under the Safeguard Mechanism to not exceed the emissions baseline applicable to their facility. The Safeguard Mechanism captures industries with a scope 1 emissions profile of 100,000+ tonnes of CO2- per year operating in the mining, oil and gas extraction, manufacturing, transport, or waste sector. In total, 215 facilities are captured. Any industry that does exceed the baseline, in theory, would either need to buy offsets for that exceedance or face penalties from the Clean Energy Regulator.

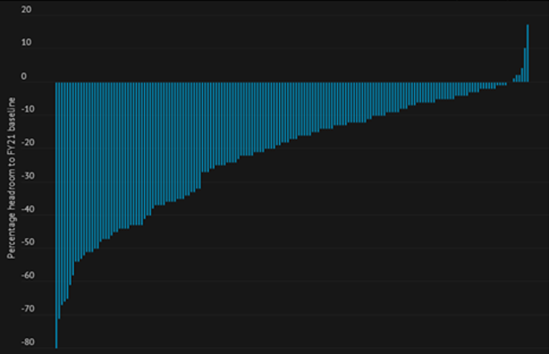

In practice, industries have rarely exceeded their baselines because, for various reasons, they are set extremely high (see figure 1) and can be revised if exceedance is likely. This has led to a situation where covered industrial emissions are increasing, rather than stabilising or reducing over time. Analysis from Reputex found that: Emissions covered by the Safeguard Mechanism have grown 7 per cent since its commencement in July 2016 … under current policy, covered emissions are projected to grow to 151 Mt by 2030 to be 27 per cent above 2005 levels (34 per cent of national emissions). This trajectory is clearly not consistent with a goal of net-zero by 2050.

Figure 1: Percentage distance between FY21 reported emissions and emissions baselines (by facility)

Source: Reputex

Proposed ALP reforms to Safeguard Mechanism

Last October, the Business Council of Australia recommended that the Safeguard Mechanism baselines be reduced ‘predictably and gradually over time’ to align with Australia’s net-zero ambition. The ALP adopted this recommendation as part of its Powering Australia policy platform, but has not gone into detail about what reformed baselines might look like. To get some idea, we can use the assumptions that Reputex relied on to model the projected impacts of revised baselines. These assumptions are:

- Resetting emissions baselines for covered facilities to reflect recently reported emissions

- Declining of an aggregate annual emissions baseline reduction of approximately 5Mt

- Tailored treatment for Emissions Intensive Trade Exposed (EITE) industries

In addition to revising the baselines, Labor has laid out in its policy platform its intent to introduce tradeable credits into the Safeguard Mechanism. This will be done by:

- Rewarding Safeguard Mechanism Credits (SMCs) to industries that beat their baseline

- Above-baseline emitters can meet their obligations by surrendering SMCs

By allowing emitters who beat their baseline to sell permits to those exceeding theirs, a “baseline and credit” emissions trading scheme is created. In theory, this can lead to an efficient carbon price across the economy. In practice, it will be highly dependent on judgmental parameters, such as the setting of baselines.

Revising the baselines

Reputex has assumed that Labor’s revised baselines will commence from July 2023, about one year from now, and will do so via regulation. This means Labor does not need to go through Parliament and will instead negotiate the revised baselines with the Clean Energy Regulator. Labor has said that to meet the 5Mt aggregate target, industries will have different baselines – recognising that some facilities have the capacity to decarbonise faster than others.

While this makes sense, there are many unknowns about how these negotiations will work, for example:

- How will “reported emissions” be determined? What if an industry contends its recent reported emissions have been distorted due to Covid-19 or market fluctuations? Will there be concessions for this?

- What if a facility expands production, meaning their total emissions increases, even if they are improving their emissions intensity, should their baseline increase?

- What happens if a facility reduces or ceases production, should they be able to claim credits?

- What is the criterion to be classed as an EITE industry?

On EITEs, the Gillard Government provided similar allowances for industries affected by the carbon price. These allowances were known as the Jobs and Competitiveness Program. It was a politically fraught process that, at least from a policymaking perspective, was not straightforward to follow. How Labor manages what are likely to be similar pressures this time round remains to be seen.

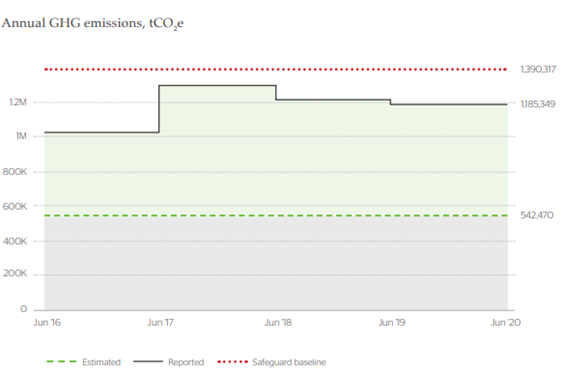

The other major question mark is the status of new projects and how this will be factored into the aggregate 5Mt reduction. Labor has already committed to supporting new gas projects like Scarborough and Beetaloo, which will have some emissions footprint. It has been a problem in the past trying to predict what the emissions footprint of a new project will be (shown in the figure below) and there is a risk any blowout could jeopardise the 5Mt/yr target.

Figure 2: Grosvenor Mine estimated emissions versus reported emissions

Source: Australian Conservation Foundation

A credits scheme

The introduction of SMCs will require legislation to be negotiated in Parliament so may commence after July 2023. Like the baseline revisions, the devil will be in the detail. At the moment, it appears SMCs will be fungible with Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs), which could result in some perverse consequences if not designed carefully.

Arguably the biggest risk is baselines being set too high, leading to a saturation of SMCs from industries beating their baselines. Reputex has already forewarned that SMC creation will have ‘considerable implications for forward ACCU price and market dynamics’ as they are likely to ‘soften compliance and voluntary demand for ACCU offsets’.

An area to watch in this space is Labor’s promised review of Australia’s carbon credit system. This promise came about following whistle-blower allegations that the scheme is not working as intended. Its outcomes may impact how ACCUs and SMCs interact with one another.

What about electricity?

Some stakeholders have asked where the electricity sector fits within all these reforms. The emissions from the electricity sector are notionally included under the Safeguard Mechanism, but unlike other industries, it is subject to a sectoral baseline. A sectoral baseline is used for electricity because the output it produces is centrally coordinated to meet demand in real time. In this sense, it acts more like a single entity.

The sectoral baseline only applies to grid-connected electricity generators and is set at 198 million tonnes CO2-e. Because the electricity sector is well below this baseline and rapidly decarbonising, some stakeholders like the Carbon Market Institute, which represents ACCU originators, have suggested also reforming the rules around electricity. Labor has indicated that it does not intend to cover electricity in its Safeguard Mechanism reforms, with it being excluded from Reputex’s modelling and separate policies being announced targeting the electricity sector.

If, however, the electricity baseline was reset such that the sector exceeded it, the rules then result in the sectoral baseline being replaced with individual facility baselines. This situation could lead to perverse outcomes, such as generators with below-grid average emissions intensity reducing dispatch in order to beat their baseline, with their output replaced by higher emissions generation.

While there might be a populist appeal in including electricity, the approach Labor has taken is pragmatic. The electricity sector is already taking great strides to decarbonise its sector and is well on a pathway to net-zero. Furthermore, it can assist other sectors in reducing their emissions through electrification, which would result in a smaller increase in electricity emissions.

The other reason why Labor’s approach makes sense is because of how different electricity’s trajectory is to other Safeguard facilities. As illustrated by the figure below, electricity sector emissions are already “predictably and gradually” declining over time whereas industrial emissions are going up. Including electricity then may simply make the aggregate 5Mt target redundant because the electricity sector can achieve that almost on its own, removing pressure on industrial facilities to play their fair share. Given that these reforms are designed to incentivise abatement in sectors where there is none, this would be counterproductive.

Figure 3: Electricity sector vs. Safeguard facility emissions (business as usual)

Source: Reputex

Generation outside the main Australian electricity grids is (if it exceeds the 100,000t threshold) subject to an individual baseline like industrial facilities. There are a few examples in remote mining arrangements who may be affected by a gradually declining baseline.

Conclusion

It will be interesting to observe how Labor manages the complexities and judgments required in recasting the Safeguard Mechanism into a Baseline and Credits scheme, each of which have major financial consequences for captured facilities. The subjective element of setting a baseline stands in contrast to the Gillard government’s Clean Energy Act, which acted on all (or “gross”) emissions and required fewer judgment calls.

This notwithstanding, Labor’s reforms to the Safeguard Mechanism represent an intent to accelerate Australia’s decarbonisation journey. Both opportunities and challenges lay ahead, but this is a necessary step forward if sectors other than electricity are to achieve net-zero.

Related Analysis

Climate and energy: What do the next three years hold?

With Labor being returned to Government for a second term, this time with an increased majority, the next three years will represent a litmus test for how Australia is tracking to meet its signature 2030 targets of 43 per cent emissions reduction and 82 per cent renewable generation, and not to mention, the looming 2035 target. With significant obstacles laying ahead, the Government will need to hit the ground running. We take a look at some of the key projections and checkpoints throughout the next term.

Certificate schemes – good for governments, but what about customers?

Retailer certificate schemes have been growing in popularity in recent years as a policy mechanism to help deliver the energy transition. The report puts forward some recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of these schemes. It also includes a deeper dive into the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme.

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.