Is minimum demand causing a major headache?

Last week the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) released the 2021 Wholesale Electricity Market (WEM) Electricity Statement of Opportunities (ESOO). The WEM ESOO provides a practical function for setting the Reserve Capacity Requirement (RCR) but it also offers an interesting insight into the future of the WEM and some of its potential challenges.

The ESOO presents a confident picture of generation meeting demand over the forecast period, in part aided by the dampening impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the growth of rooftop solar PV. The flipside is that the ESOO singles out the massive uptake of rooftop solar PV for causing a significant near-term issue – the growth of rooftop solar PV capacity is causing minimum demand levels to plummet and that puts system security at risk.

Here we look at some of the key findings of the WEM ESOO and then delve into the growth of rooftop solar PV and the challenges it creates for the South West Interconnected System (SWIS).

ESOO forecasts excess capacity

The ESOO is prepared annually by AEMO to help market participants, new investors and stakeholders make informed decisions about opportunities in the WEM over a 10-year period. It provides a wealth of data about the market, providing a valuable snapshot of committed capacity, new developments, and emerging issues.

The WEM ESOO also performs an important purpose in determining the RCR, which is the amount of capacity that is required to meet the 10 per cent probability of exceedance (POE) peak demand forecast plus a small margin. The ESOO sets the RCR at 4,396MW for the 2023-24 capacity year, a slight decrease from 4,482MW in 2021-22 and 4,421MW in 2022-23. Interestingly, this means that excess capacity in the market (i.e. total capacity minus the RCR) is expected to increase from 386MW (8.7 per cent) for 2022-23 to 411MW (9.4 per cent) for 2023-24, largely due to lower forecast peak demand.

Sufficient capacity is also expected to be available to meet forecast demand despite the staged retirement of Muja C unit 5 (195MW) in 2022 and Muja C unit 6 (193MW) in 2024. The Minister for Energy, Bill Johnston, has claimed this as a success saying that his “careful planning will keep the lights on for the next 10 years.”[1]

The growth of rooftop solar PV

Having excess capacity in the market gives the market some breathing room during peak demand events. The flipside to this are instances of low demand which can threaten the reliability of the system. To start looking at this, it’s helpful to consider what contributes to low demand and the ESOO points to one main culprit: rooftop solar PV.

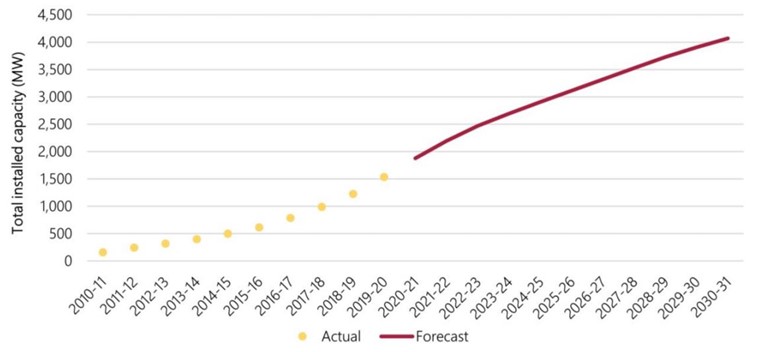

The booming rooftop solar PV market is well documented. The AEC’s quarterly Solar Report explains that the amount of new rooftop solar and the size of those installation are steadily increasing. In Western Australia, rooftop solar PV is the largest single generator in the SWIS, with 1.74 GW installed as of April 2021 representing a capacity greater than the sum of the six largest scheduled generators. According to the ESOO, in 2020, there was a 25.3 per cent increase in installed behind-the-meter PV capacity and now over 36 per cent of WA dwellings have behind-the-meter solar PV installations. AEMO expects that technological, commercial, and regulatory factors, as well as increasing environmental awareness, will further drive the strong uptake of rooftop solar PV in the SWIS from 1,740 MW in 2020-21 to an expected 4,069 MW by 2030-31.

Figure 1: Actual and forecast total installed behind-the-meter PV, 2010-11 to 2030-31

Source: AEMO, 2021 ESOO

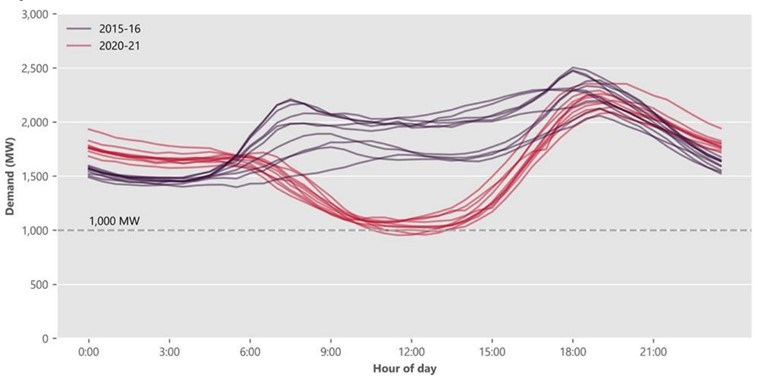

The huge growth in rooftop solar PV installation, plus the big jump in the size of each installation, has shifted when consumers are demanding energy from the network. In the past, minimum demand typically occurred during overnight periods when residential and commercial energy consumption was low. However, the growth in rooftop solar PV has brought minimum demand forward to between 10am and 2pm when the solar systems are working at their peak.

The below figure shows how the time of minimum demand has shifted considerably between 2015-16 and 2020-21, due to the increasing amount of rooftop solar PV, and created the ‘duck curve’ during the middle of the day.

Figure 2: Comparison of demand on the 10 low demand days for 2015-16 and 2020-21

Source: AEMO, 2021 ESOO

Minimum demand records tumble

The pace at which the time of minimum demand has shifted through the day is perhaps a reflection of just how much the energy sector has changed in a short period. However, rooftop solar PV is also having a major impact on the level of minimum demand – and this has far bigger consequences.

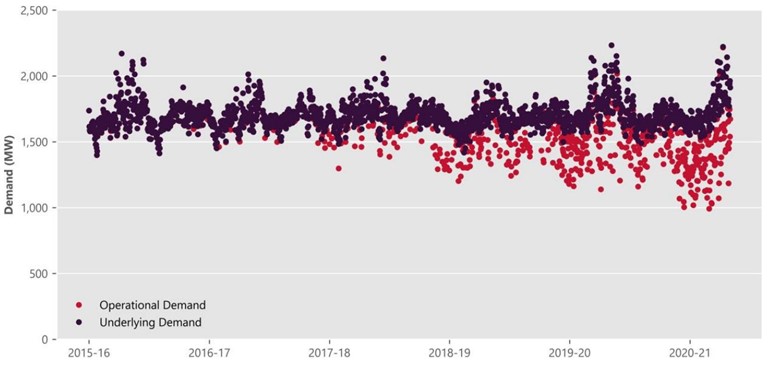

According to AEMO, the proliferation of rooftop solar PV has reduced daily minimum demand by 265MW (on average) between October 2020 to February 2021, with annual minimums in demand decreasing at an average annual rate of 7.9 per cent between 2015-16 and 2020-21.

This trend has created a growing divergence between underlying demand (i.e. demand from the network plus an estimation of rooftop solar PV and battery storage), which has stayed relatively consistent, and operational demand (i.e. demand from the network) which is declining. Put simply, we are consuming roughly the same amount of energy, but a larger portion of that energy is now coming from rooftop solar PV (see figure 3 below)

Figure 3: Daily minimum load, 2015-16 to 2020-21

Source: AEMO, 2021 ESOO

Highlighting this divergence and the speed of change in the market, the previous minimum demand record of 1,138MW (set on 4 January 2020) in last year’s WEM ESOO has now been broken six times. These records occurred on sunny, mild days in the period between late winter and spring when rooftop solar PV is producing full output and there is less need for heating or cooling.

The current minimum demand record now stands at 954MW. This occurred between 11:30am and 12:00 noon on 14 March 2021.This day also set a record for behind-the-meter solar PV reducing demand by 1,130MW.

The problem with low demand

A lot of conversation about ‘keeping the lights on’ focuses on ensuring there is enough generation capacity to meet peak demand. The reverse situation, when demand is too low, also has major consequences for system stability.

In 2019, AEMO produced a paper which considered the security risks and market impacts from falling demand. In that paper, AEMO said that the minimum level of operational demand required for system security is about 700MW.

The latest version of the WEM ESOO forecasts that minimum demand will decline rapidly to 232MW by 2025-26.

The growth of rooftop solar PV and the projected low levels of minimum demand presents a serious challenge for AEMO, generators and Western Power. The huge swings in demand as rooftop solar PV comes offline in overcast conditions requires a quick ramp up from generators to meet operational demand, which is often followed by weather changes and a rapid increase in PV output forcing generators to ramp down. These swings put pressure on a generation fleet featuring some units that aren’t suited to quick ramp ups, creating a higher risk of unit failure.

AEMO used an example of an event on 8 December 2020 to highlight the risks associated with changing output from rooftop solar PV forcing quick ramp rates:

“on 8 December 2020, when reserve margins were tight, two large-scale generators went on Forced Outage due to failures following a request to start up, joining another large-scale generator already on Forced Outage for the same reason. This sequence of events did not lead to a supply shortfall, because the forecast peak load was lower than anticipated. However, it does highlight an increasing concern in managing operational challenges.”

The other issue that is created when operational demand falls below the minimum level is the power system will fall into an unsecure operating state and it becomes vulnerable to blackouts. AEMO said in its 2019 report:

“Under these circumstances, the first response would be to constrain off non-synchronous generation and constrain on synchronous generation to prevent system collapse. However, instances can arise, although they are rare, where a level of shedding of DER is required to maintain system security."

This is clearly a situation that everyone wants to avoid and it partly triggered the Energy Transformation Implementation Unit, which sits within Energy Policy WA (EPSA), to establish the Energy Transformation Strategy (ETS). The aim of the ETS was to deliver secure, reliable, sustainable and affordable electricity to Western Australians while supporting the high penetration of behind-the-meter solar PV and other distributed energy resources. While the ETS has now come to an end (the remaining activities will be led by EPWA), it has implemented a raft of reforms and changes. Some of these have been technical, like changing the Australian Standard for inverters to include a mandatory requirement for all new inverters to have a voltage disturbance ride-through capability to help maintain security and reliability in the SWIS. Others have been more fundamental, including amending the WEM Rules and Electricity Networks Access Code 2004, and a few have been contentious, such as allowing Western Power to have network connected battery storage (See Will network operators batteries hurt competition? you can read more here). In total, they are addressing an urgent need to maintain system security operating in an environment where rooftop solar PV is pushing down minimum demand levels.

Should we worry?

The WEM ESOO gives a valuable insight into the emerging issues that are worrying AEMO. At least for the short term, it appears that AEMO is comfortable with generation matching demand. More worrying is the explicit nature of AEMO’s warning about rooftop solar PV causing minimum demand to drop to new, record levels and the impact that will have on system security.

“As the number of behind-the-meter PV installations continues to grow, AEMO expects that new minimum demand records will continue to be set. As these low demand levels continue, management of the SWIS will become increasingly challenging. AEMO is aware of the need for market and operational intervention to ensure the system stays secure and stable.”

The dilemma is that rooftop solar PV capacity is expected to further grow over the next decade while the system relies on synchronous generators as the backstop, but these units often are not suited to the quick ramp rates required by changes in solar output. The WA Government through EPWA has been addressing this issue head-on over the last few years through a series of reforms and changes. The WEM ESOO makes clear that this issue will remain challenging for some time to come.

It is also worth reflecting on the overall design of the WEM. The RCM underpins the firm generation capacity to meet an extreme demand. The RCM is also the principle economic signal to fund generation capacity, and because of this, the energy and ancillary services markets are capped at low levels, being designed to fund operating costs, rather than capital costs.

However the ESOO shows that in future total amount of firm generation capacity at time of peak is not necessarily the main concern. Characteristics such as ramping and ability to shut down and start quickly are becoming more critical requirements. The nature of the price capping tends to dampen the market’s natural signals to encourage investment in these characteristics.

[1] Speech to Parliament of Western Australia, 22 June 2021.

Related Analysis

Data Centres and Energy Demand – What’s Needed?

The growth in data centres brings with it increased energy demands and as a result the use of power has become the number one issue for their operators globally. Australia is seen as a country that will continue to see growth in data centres and Morgan Stanley Research has taken a detailed look at both the anticipated growth in data centres in Australia and what it might mean for our grid. We take a closer look.

Energy Dynamics Report - A Tale of Minimum Operational Demand and Wholesale Price declines

The third quarter saw significant price declines compared with the corresponding quarter in 2022 right across the NEM. At the same time with increased output from solar and wind generation inin Queensland’s case, minimum operational demand records were set or equaled in every region. The quarter also saw the highest-ever level of negative price intervals with all regions showing an increase. We dive in to the pricing and operational demand detail of AEMO’s Q3 Quarterly Energy Dynamics Report.

Data centres: A 24hr power source?

Data centres play a critical role in enabling the storage and processing of vast amounts of online data. However they are also known for their significant energy consumption, which has raised concerns about their environmental impact and operating costs. But can data centres be fully sustainable, or even a source of power?

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.