Household trends: What do they mean for power generation?

With rising urbanisation and people moving closer to city centres, how will the future power system provide electricity to households? Urbanisation is creating two distinct categories of residential energy use. The first lives in more densely populated city areas and are dependent on the electricity grid and large generation plants for electricity. The other category lives in the suburbs or regional areas with larger, detached dwellings and have a greater ability to take up distributed generation and battery technology.

Australia’s population is increasingly living in urban areas. In 2015, around two-thirds or 15.9 million Australians lived in a Greater Capital City[i]. As the population grows, the increasing number of people commuting into central business districts at the start and end of the day causes increases commute times. In response, more people are electing to live closer to their workplaces and closer to major capital cities to ease their travel times and increase leisure time.

Urbanisation is the increase in the proportion of the population living in cities, and it is happening in Australia. The number of Victorians living in Greater Melbourne[ii] has been rising at an annual average growth rate of 2.1 per cent over the past 5 years, which compares to 1.8 per cent growth in the rest of Victoria over the same period[iii]. As a result, the ABS projects the share of Victoria’s population living in Greater Melbourne will rise from 76 per cent in 2016, to 81 per cent in 2056,[iv] a trend that is expected across Australia.

Figure 1 Share of population in Greater Melbourne compared to rest of Victoria

Source: ABS, Australia’s Demographic Statistics, 2016.

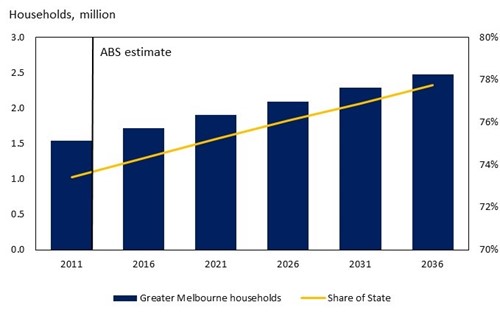

The number of households in urban areas is also expected to account for a larger share of the state’s population. At the same time that a large a larger proportion of the population is choosing to live closer to city centres, the number of people per household is declining, increasing growth in households. Household growth in Greater Melbourne is expected to outpace household growth in the state, resulting in a greater share of households living in urban areas (Figure 2)[v]. As the number of households rise, and the number of people per household falls the per capita use of basic services like water, electricity, food and waste services is expected to rise.

Figure 2: The level and share of Victoria’s households living in Greater Melbourne

Source: ABS, Australia’s Demographic Statistics, 2016; ABS, Household Projections, Australia, 2011 to 2036.

As more people move into Australia’s cities many of them will live in rental accommodation and apartments, where there is little incentive, or ability to install and use distributed generation, such as solar panels, solar hot water systems or battery storage. In 2003-04 22.3 per cent of Victoria’s population were renting and by 2013-14 this had increased to 28.2 per cent[vi].

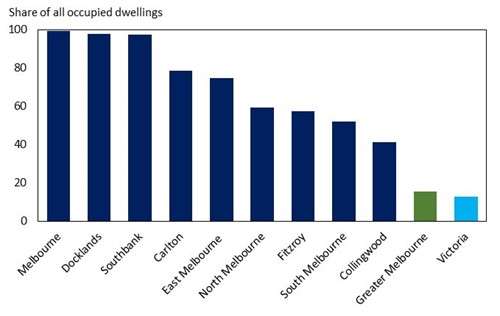

Figure 3 below shows that in inner Melbourne areas, a large proportion of dwellings are apartments, units or flats- much higher than the state total share of apartments of just 13 per cent.

Figure 3 Units, flats and apartments as a share of all occupied dwellings, by small area and region

Source: ABS, Census 2011.

As more people choose apartment living, the urban centre of capital cities will become more reliant on the grid to supply energy and this energy is still likely to be generated outside the city by large generation plants. Even where solar PV can be installed on apartment buildings there will be limited capacity, particularly in comparison to the level of demand from residents.

The urban sprawl or growth in suburban boundaries further away from city centres is creating a second category of very different residential energy consumers. Households in suburbs and regional areas are much more likely to live in separate houses, with the ability and space to take advantage of distributed generation. While growth in household numbers in regional areas is slower than in capital cities, a large share of the population in the outer capital city suburbs and regions will live in separate houses. At the same time, the ABS expects the average number of persons per household to decline across Australia to 2036, and as a result, the per-household use of services will rise in these outer urban and regional areas. Although the final use of energy is difficult to predict because the average house size is rising with people building larger houses, requiring more energy to live in. But these households are in a position to avoid using the grid for part of the day as they generate and consume their own electricity.

Current trends of urbanisation are likely to lead to a divergence in residential energy consumption. With the forecast growth in city living we are likely to see that the electricity grid continues to be required to transport electricity from regional areas with high energy resources to load centres in cities. In contrast, residential consumers in suburbs and regional areas will be able to shift towards more distributed generation and batteries, and rely on their own generation for part of the day. Whether it makes sense for consumers in all but the most remote areas to go fully “off-grid” remains to be seen.

[i] ABS, 2016, catalogue number 3218.0, Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2014-15.

[ii] Greater Melbourne Statistical Area defined as the Australian Bureau of Statistics ASGS area,http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/Australian+Statistical+Geography+Standard+(ASGS)

[iii] Victorian Government, 2016, Victoria in the Future 2015,http://www.delwp.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/308243/Greater-Melbourne-2GMEL_VIF2015_One_Page_Profile.pdf

[iv] ABS, 2016, catalogue number 3101.0, Australia’s demographic statistics, Sep 2015.

[v] ABS, 2015, catalogue number 3236.0, Household and Family Projections, Australia, 2011 to 2036.

Note: Series I projections assume no change in propensities. Living arrangement propensities for 2011 remain constant to 2036.

[vi] ABS, 2015, catalogue number 4130.0, Housing Occupancy and Costs, 2013-14,http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/4130.02013-14?OpenDocument

Related Analysis

Consumer Energy Resources: The next big thing?

The Consumer Energy Resources Roadmap has just been endorsed by Energy and Climate Change Ministers. It is considered by government to be the next big reform for the energy system and important to achieving the AEMO’s Integrated System Plan (ISP). Energy Minister, Chris Bowen, recognises the key will be “making sure that those consumers who have solar panels or a battery or an electric vehicle are able to get maximum benefit out of it for themselves and also for the grid”. There’s no doubt that will be important; equally there is no doubt that it is not simple to achieve, nor a certainty. With the grid intended to serve customers, not the other way around, customer interests will need to be front and centre as the roadmap is rolled out. We take a look.

Australia’s workforce shortage: A potential obstacle on the road to net zero

Australia is no stranger to ambitious climate policies. In 2022, the Labor party campaigned on transitioning Australia’s grid to 82 per cent renewable energy by 2030, and earlier this year, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese unveiled the Future Made in Australia agenda, a project which aims to create new jobs and opportunities as we move towards a net zero future. While these policies have unveiled a raft of opportunities, they have also highlighted a major problem: a lack of skilled workers. Why is this a problem? We take a closer look.

Made in Australia: The Solar Challenge

While Australia is seeking to support a domestic solar industry through policy measures one constant question is how Australia can hope to compete with China? Australia currently manufactures around one per cent of the solar panels installed across the country. Recent reports and analysis highlight the scale of the challenge in trying to develop homegrown solar manufacturing, as does the example of the US, which has been looking to support its own capabilities while introducing measures to also restrict Chinese imports. We take a look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.