Decarbonising aviation – in it for the long haul

Up until recently, the aviation sector has avoided policymaker attention – at least as far as carbon reduction policy goes. This has started to change with the Federal Government’s publication of an Aviation Green Paper, which attempts to navigate the foggy skies of how to align aviation with a net-zero by 2050 future.

Here we take a look at some of the options for aviation decarbonisation and the challenges policymakers face.

Putting aviation emissions into context

When the Quarterly Update of Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory was released back in August, the headline story was the ongoing reductions in electricity emissions, which declined 3.9 per cent in the year to March 2023. This was driven by a drop in coal generation (4.7 per cent) and an uptick in renewable generation (18.6 per cent). The Federal Government’s media release pointed out that these trends saw renewable generation account for 39 per cent of total generation across the National Energy Market for that inventory period.

But buried beneath that good news was a marked increase in transport emissions, driven mainly by aviation. Both the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water and Government acknowledged that emission increases in other sectors, particularly transport, had mostly offset the efforts of the electricity sector. Over the year to March 2023, transport emissions increased by 6.4 per cent, driven by a 63.4 per cent increase in emissions from domestic aviation. This increase has placed domestic aviation sector emissions at their highest quarterly point since December 2017.

Decarbonising aviation

The task of decarbonising domestic aviation is a tricky one for policymakers. Aviation is accepted as a hard-to-abate sector, where no clear commercial alternatives exist to conventional jet fuel. This means rushing in cleaner fuel substitutes will only add costs at a time when airline costs are already facing strong public scrutiny. There is also no margin for error when it comes to safety – any new technology must be fully proven and capable from day one.

Then, on top of all that, there is the political reality: aviation emissions represent a relatively small percentage of Australia’s overall emissions (about 3 per cent), so decarbonising this sector is not critical to reaching the Federal Government’s 2030 target.

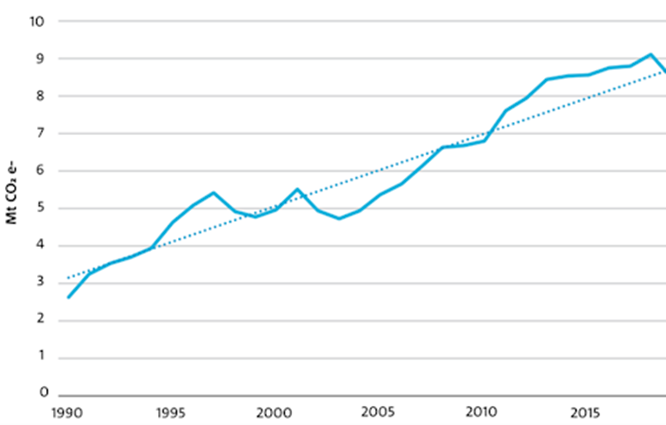

Even still, this three per cent is relative and will balloon as other sectors decarbonise, while airlines themselves now face Safeguard obligations to begin reducing their emissions. These obligations come at a time when their emissions are increasing and projected to continue: “domestic aviation emissions in Australia have more than tripled between 1990 and 2019. This is coupled with projections for Australian jet fuel demand increasing by 75 per cent from 2023 to 2050”.[1]

Figure 1: Australian domestic aviation emissions

Source: CSIRO Sustainable Aviation Fuel Roadmap, p5.

This has not stopped Australia’s largest airline, Qantas, pledging to reduce its emissions by 25 percent by 2030 (based on 2019 levels) while its major competitor, Virgin, has also promised a 15 percent reduction by 2030 (also using 2019 levels). Both aim to be net-zero by 2050.

So what are the options for getting there?

Sustainable Aviation Fuel

Sustainable Aviation Fuel (‘SAF’) is seen as having the most near-term commercial potential. SAF is a broad term with no universal definition other than the fuel being non-fossil derived. Common sources of SAF are feedstock, biofuels, synthetic fuels, renewable electricity, and hydrogen-based fuels. Qantas estimates that, when compared to conventional jet fuel, SAF can reduce aviation emissions by up to 90 per cent, as well as significantly improving air quality due to lower particulate and sulphur emissions.

Many overseas jurisdictions have begun implementing policies to incentivise investment in SAF, including:

- In the European Union, jet fuel will need to be 2 per cent SAF by 2025, increasing at 5-year intervals to reach 70 per cent in 2050.

- The UK will introduce a mandate in 2025 for 10 per cent SAF by 2030.

- The US has set a SAF production target of at least 3 billion gallons per year by 2030.

Meanwhile in Australia, the Federal Government recently committed $30 million to a Sustainable Aviation Fuel Funding Initiative, while also releasing the aforementioned Aviation Green Paper that seeks stakeholder input on how the government can promote SAF uptake.

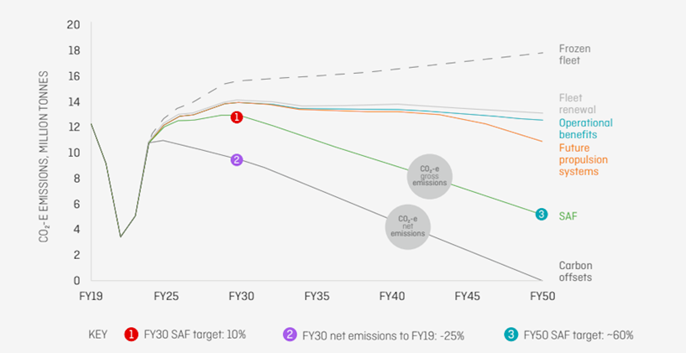

This all builds on a commitment from Qantas to begin purchasing SAF so it can reach 10 per cent SAF by 2030 and 60 per cent by 2050.

Conveniently, the CSIRO last month published its Sustainable Aviation Fuel Roadmap. While identifying SAF as the best pathway for aviation decarbonisation, it cautioned it remains a nascent fuel: “uncertainty in feedstock and technology choice, slow deployment and higher production costs have limited investment in large-scale projects, resulting in approximately 300 ML of global SAF produced in 2022, or approximately 0.09 per cent of fuel sales that year”.[2]

Electric Planes

At the recent Carbon Market Institute Summit, Minister Bowen remarked that Australia can expect to see electric planes over the next decade for short-haul flights. Planned attempts by regional airline Rex to begin retrofitting some existing fleets with electric propulsion engines (to be powered by both batteries and hydrogen) offers some hope that this future is not too far away.

However, most analysts have tempered expectations around the prospects of electric planes. Both Qantas and Virgin have stated their intent is to focus investment in SAF, and that electric aviation does not currently represent a commercial reality. The CSIRO’s assessment is even more sobering:

While battery-powered planes have been successfully flown in demonstrations, it may take some time before they become widely available and without step changes in battery technology, will only be suitable for short-haul flights. Using new fuels such as hydrogen in fuel-cells or combusted in turbines for longer-haul flights will face significant technological and supply chain challenges, such as developing onboard hydrogen storage and establishing large-scale production and distribution of green hydrogen fuel. Creating the necessary refuelling and recharging infrastructure and large-scale manufacturing capabilities will require significant time and investment, and costs are currently unclear.[3]

Flight alternatives

Some European countries have started to encourage alternative transportation methods, in particular high-speed rail, for short-haul flights. France and Austria, for example, have banned flights if there is an available train option with a journey under 2.5 hours.

Unfortunately, Australia’s large size but low population density makes uptake of alternative transport methods for short-haul flights mostly unrealistic. The most talked about alternative – high-speed rail – has been floated many times before in Australia, but no action has ever been taken due to cost concerns. The Grattan Institute has estimated costs for a Melbourne to Sydney line to be approximately $10,000 per taxpayer.

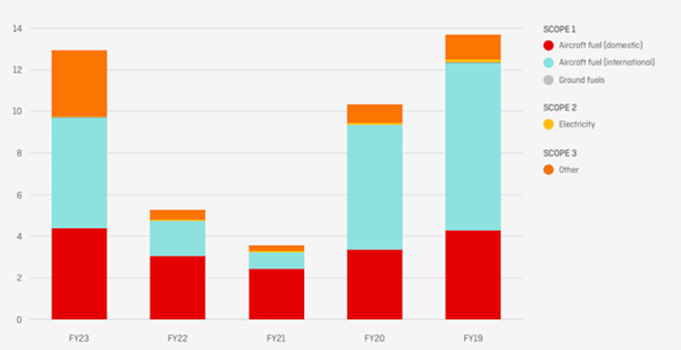

Furthermore, Australia’s geographical isolation means a higher proportion of its aviation emissions come from international rather than domestic travel, as the figure below shows.

Figure 2: Qantas Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Source: Qantas Sustainability Report 2023, p34.

Carbon Offsets

Given current restraints – both commercial and technological – on aviation decarbonisation technologies, it seems probable airlines captured under the Safeguard Mechanism will rely on the surrendering of offsets to remain compliant. This is not a problem per se – after all, this is what carbon offsets are designed to be used for, to help hard-to-abate sectors begin decarbonisation while nascent technologies remain commercially unviable.

The challenge is, of course, how to cost-effectively transition from offset reliance to new low-carbon technologies. Interestingly, Qantas’ long-term decarbonisation pathways maintains a strong reliance on offsets, albeit with the promise that it will use high-quality and high-integrity offsets: offsets are estimated to contribute 50-60 per cent of Qantas’ emissions reductions by 2030, and 30-40 per cent by 2050.

Figure 3: Qantas Group Emissions Pathway

Source: Qantas Sustainability Report 2023, p22.

Conclusion

With airline practices under the spotlight, and carbon policy always under the spotlight, the Federal Government’s upcoming transport sectoral pathway will make for interesting reading. There remains a tough balancing act between the Government’s economy-wide expectation that all sectors decarbonise, and the commercial reality that technological alternatives for aviation are not there yet.

[1] CSIRO, ‘Sustainable Aviation Fuel Roadmap’, August 2023, p5.

[2] CSIRO, ‘Sustainable Aviation Fuel Roadmap’, August 2023, p12.

[3] CSIRO, ‘Sustainable Aviation Fuel Roadmap’, August 2023, p11-12.

Related Analysis

Climate and energy: What do the next three years hold?

With Labor being returned to Government for a second term, this time with an increased majority, the next three years will represent a litmus test for how Australia is tracking to meet its signature 2030 targets of 43 per cent emissions reduction and 82 per cent renewable generation, and not to mention, the looming 2035 target. With significant obstacles laying ahead, the Government will need to hit the ground running. We take a look at some of the key projections and checkpoints throughout the next term.

Certificate schemes – good for governments, but what about customers?

Retailer certificate schemes have been growing in popularity in recent years as a policy mechanism to help deliver the energy transition. The report puts forward some recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of these schemes. It also includes a deeper dive into the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme.

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.