Carbon credits: Will they continue to rise in price?

Last week the Federal Government announced it would extend consultation on its contentious proposal to allow the Minister for Agriculture to veto certain carbon credit projects.[i] The debate around this proposal comes on the backdrop of skyrocketing demand for Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs), and with it, pressure for increased supply.

So, what is driving this demand and how is Australia’s carbon market likely to respond to these evolving market pressures?

Australia’s carbon credit market

Carbon credits are a permit that allow a company or country to offset its emissions. A company will receive one credit for every tonne of carbon emissions either stored or avoided.

In Australia, ACCUs are administered under the Federal Government’s Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) with the Clean Energy Regulator (CER) being responsible for issuing ACCUs (learn more here). To receive an ACCU an abatement project must satisfy the principle of ‘additionality’ - that the project would not have occurred otherwise. This is not easy to prove, and Australia sets a fairly high bar.

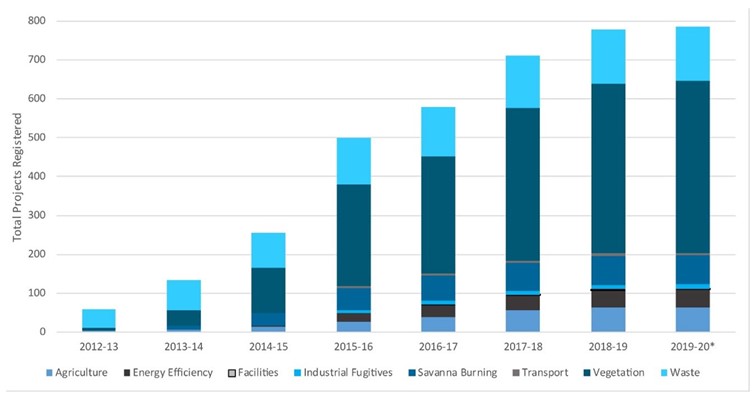

As figure 1 shows, the types of projects where the CER has issued ACCUs are overwhelmingly vegetation[ii], waste,[iii] or savanna burning[iv] projects.

Figure 1: Cumulate ERF projects registered by method type

Source: CER

Recent developments in Australia’s carbon credit market

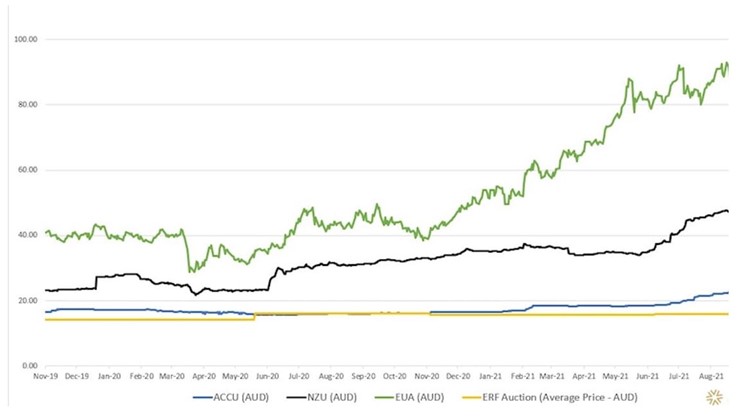

In line with the Federal Government’s mantra of “choices not mandates”, participation in Australia’s carbon credit market is voluntary. This is different to overseas carbon credit markets, such as in the European Union (EU), where an Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) is in force. In that, companies in covered industries are legally obliged to purchase a right to emit carbon, known as a European Union Carbon Allowance (EUA), against all their emissions. The obligation, combined with the EU’s more ambitious carbon policies, and the absence of relatively low-cost abatement opportunities, mean EU prices have grown very strongly, and are about double the price of ACCUs. Australia does not allow ACCUs to be exported, so EU companies cannot surrender them in lieu of an EUA. If they could, the ACCU price would likely be dragged up to the EUA price.

Figure 2: Carbon closing prices (AUD) to August 2021

Source: ABC

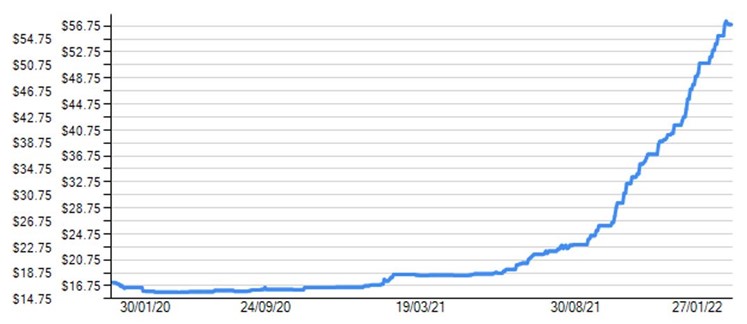

This makes the recent dramatic spike in prices for ACCUs since last August, shown below, all the more interesting.

Figure 3: Spot Price of ACCUs

Source: Jarden

What is driving this sudden demand?

It appears a confluence of factors has caused the recent surge in demand for ACCUs.

At a political level, the Federal Government’s commitment to net-zero by 2050 means there is now bipartisan support for reaching this target, with the Labor Party promising to legislate such a goal. Labor has also promised to gradually tighten the baselines under the Safeguard Mechanism, which could potentially compel companies to purchase carbon credits to remain legally compliant (in other words, to cover any gaps that emerge between a company’s actual emissions and its reduced baseline). With the upcoming federal election approaching, the possibility of a change in government may be fuelling speculative demand.

Internationally, the COP26 in Glasgow provided a wave of climate momentum and culminated with countries agreeing to a new set of rules for regulating international carbon markets. These rules intend to improve the integrity and transparency of carbon credits so are expected to increase the demand for high-quality credits.

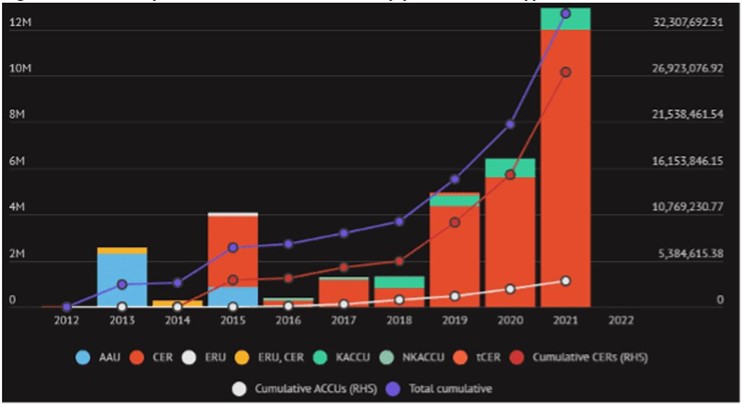

ACCUs are considered high-quality credits due to the stringent processes the CER has in place when issuing. This extra layer of environmental integrity serves as a premium on their price. Carbon credits with less stringent additionality rules, such as the United Nations’ Certified Emissions Reduction units, are considerably cheaper (around $1-2AUD) and consequently remain the dominant form of offset for Australian companies. Carbon consultancy firm, Reputex, found over 90 per cent of cancellations were in the form of Certified Emission Reductions.

Figure 4: Voluntary cancellations in Australia by year and unit type

Source: Reputex

The reliance on internationally sourced credits by corporations to meet their climate pledges, along with the growth in the number of corporations making such pledges, has led to concerns around greenwashing and with it, louder calls for transparency over the quality of credits companies are relying on. This scrutiny is increasing the demand for high quality credits, something the CER noted in its most recent Quarterly Carbon Market Report:

“There has been increasing media interest in providing transparency on the provenance of international carbon units being cancelled in large numbers by Australian corporates. This is expected to continue, progressively shifting demand to high quality ACCUs”.

The demand for ACCUs may also partly be driven by the bandwagon effect, with speculative investors jumping into a market they see as undervalued relative to overseas prices.

What are the implications of this growth in demand?

In an economy covered by a mandatory ETS, the rising price of carbon credits should compel companies to weigh up whether it is more economically efficient to directly reduce their emissions rather than purchase instruments. How this trade-off works though in a voluntary market remains to be seen. Since companies are not legally compelled to make a choice, if the price becomes too high, companies may seek to withstand social or investor pressure and continue to rely on international credits or simply cease offsetting until the price declines.

Connected to all this is the ability of supply to keep pace with demand. Even in a large country like Australia, land is a scarce resource and land-use based offsets, the dominant type of ACCU projects, have already exhausted the lowest cost abatement opportunities. This means then going forward that new supply projects must either contest for more premium land or find alternative supply avenues. As far as the latter goes, the Federal Government recently announced that credit abatement can be issued for new carbon capture and storage projects, and is considering other project types. But quantity is ultimately limited by the tight scope of Australia’s additionality rules.

As for the former, the proposal to allow the Minister for Agriculture to veto certain carbon credit projects has brought to the fore the contest over premium land. The proposal reflects concern from some stakeholders that locking away large blocks of land for vegetation or reforestation provides few jobs for regional areas and may consume prime agricultural land. Other stakeholders say it unnecessarily increases the costs of decarbonisation and undercuts a growing revenue stream – companies are paying more for credits from nature-based projects since it is associated with environmental integrity.

Either way, these tensions over supply will not disappear anytime soon and arguably raise a larger question about the role of carbon credits in decarbonisation. Carbon credits exist to supplement, not substitute, direct and actual emissions reduction activity. For hard-to-abate sectors like aviation, this is where carbon credits step in. For other sectors like transport, where decarbonisation opportunities like electrification are readily available, carbon credit use should be marginal.

As voluntary demand grows, the tensions over supply should serve as a reminder that no amount of carbon credits can offset the emissions reductions required to get Australia to net-zero by 2050.

[i] The veto power would only apply to new or expanded native forest regeneration projects that make up more than a third of the farm and are larger than 15 hectares in area.

[ii] Vegetation is largely the replanting of previously cleared land, or the avoidance of planned clearing.

[iii] Waste is principally the capture and elimination of methane emissions from landfill.

[iv] Certain approaches of fire management of savannah (monsoonal) forest emit less carbon.

Related Analysis

Climate and energy: What do the next three years hold?

With Labor being returned to Government for a second term, this time with an increased majority, the next three years will represent a litmus test for how Australia is tracking to meet its signature 2030 targets of 43 per cent emissions reduction and 82 per cent renewable generation, and not to mention, the looming 2035 target. With significant obstacles laying ahead, the Government will need to hit the ground running. We take a look at some of the key projections and checkpoints throughout the next term.

Certificate schemes – good for governments, but what about customers?

Retailer certificate schemes have been growing in popularity in recent years as a policy mechanism to help deliver the energy transition. The report puts forward some recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of these schemes. It also includes a deeper dive into the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme.

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.