What does the Queensland Energy Roadmap mean for the 2026 ISP?

The Queensland Government recently unveiled its new Energy Roadmap for the state. The new Roadmap reshapes the pace and scale of the state’s energy transition by opting to retain the state’s existing coal assets in Queensland’s generation mix for longer.

Somewhat coincidentally, the AEMC has started consultation on the “treatment of jurisdictional policies” like the Queensland Energy Roadmap in AEMO’s Integrated System Plan (“ISP’) as part of its broader Statutory Review of the ISP.

So what does Queensland’s new Roadmap mean for AEMO’s signature whole-of-system electricity plan?

Queensland’s Energy Roadmap in a nutshell

The main elements of the new Roadmap are:

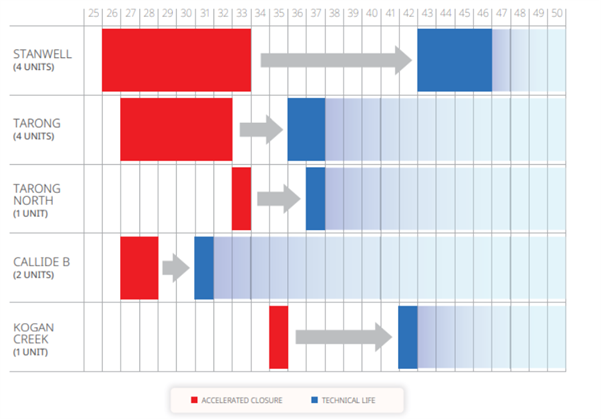

- Queensland’s government-owned coal fleet is now expected to run out until at least 2046 (the Queensland Energy and Jobs Plan under the previous government had brought forward closure to 2035). Figure 1 below illustrates the new coal closure dates. These revised timeframes are backed by a $1.6 billion Electricity Maintenance Guarantee to maintain the technical health of these assets.

- A $400 million Queensland Energy Investment Fund and creation of Queensland Investment Corporation’s new Investor Gateway to drive private sector investment in new energy generation and firming projects. The Roadmap projects a need for up to 6.8 GW of wind and large-scale solar and up to 3.8 GW of storage by 2030.

- A tender for 400MW of new gas-fired generation in Central Queensland alongside government-owned generators being primed to invest in over 700 megawatts (MW) of new gas fired generation capacity. This is on the back of the Roadmap projecting at least 2.6GW of new gas-powered generation being needed by 2035.

- Construction of the Eastern Link of the CopperString transmission line in North Queensland and beginning of work on the Western Link.

While announced earlier, part of the action plan involves repealing Queensland’s renewable energy targets of 50 per cent by 2030, 70 per cent by 2032 and 80 per cent by 2035.

Overall, the Queensland Government says this Roadmap will reduce whole-of-system energy costs by around $26 billion to 2035, compared to the accelerated coal closures outlined under the previous version.

This new direction puts it in tension with AEMO’s ISP which has modelled a transition pathway based around meeting the Federal Government’s 82 per cent renewable electricity target.

Figure 1 – Indicate operating timeframe of state-owned coal-fired assets

Source: Queensland Energy Roadmap, p29.

The ISP and treatment of jurisdictional energy policies

The past few years have seen the Integrated System Plan gain a life of its own. What started as a planning document for transmission businesses has morphed into (in AEMO’s words):

“a roadmap for the transition of the National Electricity Market (NEM) power system [which] outlines the mix of generation, storage and network investments required to meet both consumer needs and government energy and emissions targets between now and 2050”.

A major driver of the ISP’s evolution is the requirement for AEMO to consider jurisdictional emissions and energy policies in pulling it together. AEMO’s Input and Assumptions Scenarios Report sets out the policies covered in the ISP, but the one that prevails over them all is the Federal Government’s 82 per cent renewable electricity target by 2030. As a result, each ISP scenario, including the Optimal Development Pathway (otherwise known as the Step Change scenario) is modelled on meeting the 82 per cent renewable electricity target.

There is subsequently ongoing debate, sometimes healthy and at other times less so, about whether it is better to characterise the ISP as a forecast of the optimal future energy grid that policymakers and industry should be working towards, or a modelling exercise that back-solves how to meet government targets at lowest cost (without contemplation of whether meeting those targets represents lowest cost).

It is in the context of this debate that the AEMC has initiated consultation on a rule change proposal to review the treatment of jurisdictional policies under the ISP, with the Queensland Energy Roadmap being a useful test case in this regard.

Can the Queensland Energy Roadmap be integrated into the ISP?

The biggest dilemma facing AEMO is how to reconcile the Queensland Government’s commitment to maintain its government-owned coal fleet beyond 2030 with the Federal Government’s target to reach 82 per cent renewable electricity by 2030.

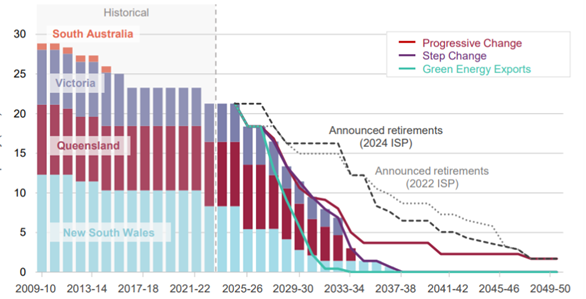

AEMO’s Step Change scenario currently has around 3,500MW of Queensland coal generation closing between now and 2030-31, which will now need to be re-evaluated.

Figure 2: Coal Capacity, NEM (GW, 2009-10 to 2049-50)

Source: AEMO Integrated System Plan, p10.

There are a few options AEMO could take:

- The market body could say that deteriorating market conditions will force coal generation out as the grid gets closer to 82 per cent renewables. The problem with this is Queensland’s coal fleet is government-owned, and that government has said market conditions favour leaving coal in the system (and even if not, have committed to maintaining them).

- The 3,500MW of coal closure scheduled in Queensland could instead be removed from Victoria and NSW’s electricity grid. While this would make the numbers add up, it is not very believable and would attract all types of scrutiny about how to maintain reliability.

- AEMO could take both assumptions at face value and model the buildout of renewable generation needed to reach 82 per cent while Queensland maintains coal in the system. This scenario would represent a massive overbuild and not a lowest cost pathway for customers.

None of these options are very ideal and might suggest a need to reshape how the ISP scenarios are presented. AEMO has taken some small steps already with the 2026 ISP to have a more clearly labelled “Slower Growth” scenario and “Accelerated Transition” scenario at either end of the Step Change scenario.

While this is helpful, it does not really resolve the ISP’s biggest challenge and that is the messaging of the Step Change scenario as the Optimal Development Pathway. This label is creating confusion because it gives the impression that the Step Change represents the lowest cost action plan of all possible future scenarios. Aside from the inherent uncertainties of economic modelling, there are different perspectives on whether reaching 82 per cent by 2030 represents lowest cost and the Queensland Roadmap is now one policy manifestation of that.

To manage these uncertainties, it would arguably be better for the ISP’s transition scenarios to be represented as neutral and used to benchmark how Australia’s transition is tracking. This might involve having three scenarios that represent different buildout rates of renewable electricity, so there is an iterative understanding of what needs to happen to reach certain milestones. The 82 per cent renewable electricity by 2030 scenario should arguably be the “Accelerated Transition” scenario given it represents the highest level of near-term ambition.

While there might be criticism that removing the Optimal Development Pathway label reduces the impact of the ISP, it may also help AEMO with another unenviable modelling task of incorporating the Federal Government’s 2035 emissions reduction target range of 62 to 70 per cent.

It’s further away, but the 2035 target and Queensland Roadmap also don’t co-exist

For all its imperfections, the 82 per cent target does give AEMO a clear modelling exercise on what the 43 per cent economy-wide emissions reduction target means for the electricity sector. The 2035 target is far more up in the air given its status as a range target and there are currently no explicit policy announcements sitting behind it.

AEMO will probably be tasked then with making assumptions about what the 2035 economy-wide target means for the electricity sector and then modelling different target range scenarios. If the current model is followed, that means one of these range scenarios will come to represent the Optimal Development Pathway for electricity, which absent government direction is arguably beyond a market operator’s remit and also unlikely to be compatible with the coal closure dates in the Queensland Roadmap.

Furthermore, if AEMO maintains the 82 per cent target as a binding constraint in all scenarios then it will reduce the value of modelling different electricity emissions pathways between 2030 and 2035. Having different scenario buildouts up to 2030 (including an accelerated 82 per cent scenario) would arguably give greater insight into how the electricity sector is contributing to the 2035 target.

Conclusion

Despite disagreements about its characterisation and outputs, the ISP is regularly the base case stakeholders use to compare and contrast likely energy transition scenarios. The review processes currently underway represent a timely opportunity to make sure the value of the ISP is being fully maximised.

Related Analysis

Powering the EV transition: Why Victoria’s Inquiry matters

Victoria has taken an important step toward Australia’s clean transport future. The Victorian Parliament’s Economy and Infrastructure Committee Inquiry into how to better align electric vehicles (EVs) with electricity supply and demand could be one of the most thorough examinations yet of the opportunities and challenges in EV integration. For the Australian Energy Council (AEC), this inquiry represents exactly the kind of structured, evidence-based policymaking needed to align rapid EV uptake with our decarbonising electricity system. The Inquiry asks the right questions; about timing, infrastructure, the consumer experience and market design. And it comes at a time when Victoria has the chance to show national leadership in linking transport and energy policy. We take a closer look at Victoria's unique position in the energy future.

Connects - The AEC's latest networking event

The Australian Energy Council will launch its new Connects series in Melbourne on 19 November 2025. The event will feature insights from the CEO Survey and a panel discussion with Shannon Hyde (ENGIE ANZ), Mark Collette (EnergyAustralia), and Nick Maher (SEC Newgate), with more speakers to come. Open to members and non-members, Connects brings together energy leaders and innovators for an evening of discussion and networking.

The ‘f’ word that’s critical to ensuring a successful global energy transition

You might not be aware but there’s a new ‘f’ word being floated in the energy industry. Ok, maybe it’s not that new, but it is becoming increasingly important as the world transitions to a low emissions energy system. That word is flexibility. The concept of flexibility came up time and time again at the recent International Electricity Summit held in in Sendai, Japan, which considered how the energy transition is being navigated globally. Read more

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.