The risk of Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms have long been flagged as part of carbon-reduction schemes around the world. While some policymakers argue that a border tariff is necessary to support a truly decarbonized economy and prevent “carbon leakage”, trading partners logically identify these charges as the imposition of carbon pricing on their domestic economies by stealth. Australia has now joined other countries in considering the suitability of a border mechanism as part of its climate approach. We take a look at carbon border tariffs emerging around the world, their rationale and their impacts on free trade.

In 2023, most advanced economies around the world have a direct or indirect carbon price. Generally, this is imposed via an emissions trading system (ETS) or a carbon tax. Additionally an estimated 133 countries representing 91 per cent of global GDP and 83 per cent of global emissions have adopted net zero emissions targets[i]. The European Union ETS, considered the first major scheme internationally, was launched in 2005 with the goal of reducing emissions across the Schengen Area. The scheme was established prior to the Kyoto Protocol coming into effect on 16 February 2005 and has since evolved through a number of stages, with further developments to come.

It is worth noting that while the scheme imposes emissions restrictions, the EU has not implemented an ideologically “pure” scheme free of protections for large emitters. There are concessions provided primarily to ensure that these emitters remained competitive with similar facilities around the world. For example, the European steelmaking industry has received free carbon permits since the ETS’ inception. This arrangement was reaffirmed as recently as October 2022. The EU is now advancing a Carbon Border Adjustment Scheme which relies on the ETS to provide a carbon price that the EU can apply to imported goods. That Carbon Border Adjustment Scheme will be progressively implemented between 2023 and 2026 (more details below).

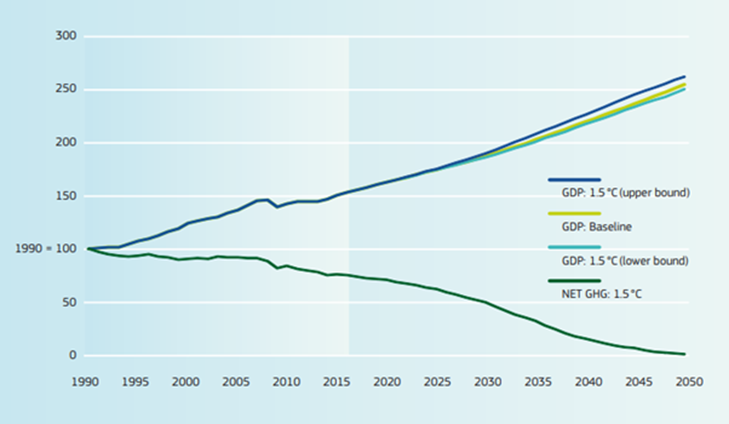

Figure 1 – EU projections of emissions reduction and economic growth to 2050

Source: The European Commission

What is a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)?

These mechanisms are primarily aimed protecting emissions-intensive trade-exposed industries with the CBAM designed to effectively subject foreign producers to the domestic climate policy of the importing country.

US think tank the American Action Forum defines a CBAM as:

A CBAM taxes carbon-intensive goods produced domestically or abroad based on an established carbon price, which is determined by the government. The border adjustment aspect of this is that the tax is based on domestic consumption of the carbon-intensive good, so products that are exported are given a rebate of the tax. A CBAM includes the rebate for exports to disincentivize moving carbon-intensive production overseas, known as carbon leakage.

Impact on trading partners

Of all trading partners, less-developed nations feel the impacts of CBAMs the most. It is correct to say that when countries and trading blocs price the carbon utilized to produce a good (at a rate assumed by the assessing nation), the economic outcome for poorer nations is an additional barrier to trade. In addition to the economic consequences, these nations may be subject to the imposition of carbon pricing on their domestic economies by stealth. While the goal of nations imposing CBAMs is to incentivize other nations to decarbonise, they risk increasing the cost base of their trade partners as a result of these requirements.

The EU’s CBAM was finalised on 13 December 2022. In its press release, the European Commission said:

“Climate change is a global problem that needs global solutions. As the EU raises its own climate ambition, and as long as less stringent climate policies prevail in many non-EU countries, there is a risk of so-called ‘carbon leakage'. Carbon leakage occurs when companies based in the EU move carbon-intensive production abroad to countries where less stringent climate policies are in place than in the EU, or when EU products get replaced by more carbon-intensive imports.”

The CBAM begins in October 2023, and commences in a “transitional period,” with iron, steel, aluminum, cement, fertilizer, electricity, and hydrogen impacted. Practically, importers will be required to report their carbon emissions to the EU on a quarterly basis.

In case the data on actual embedded emissions for the producer are not be available, the EU proposes to use default emissions data which would be based on emissions of 10 per cent of the least efficient producers in the EU in the relevant industry, rather than the actual emissions created when the goods were produced by the trading partner.

From 2026, importers will be required to purchase CBAM certificates, which importantly will be linked to the EU’s ETS carbon price. The reach of the CBAM remains somewhat unclear, with a December 2022 statement from Brussels saying methodology to be defined in the meantime:

“The agreement foresees that indirect emissions will be covered in the scope after the transitional period, on the basis of a methodology to be defined in the meantime.”

Global opposition to the CBAM

Notably, Japan and the United States have expressed opposition to the EU’s CBAM. However, each jurisdiction has taken a different approach in their opposition.

The Clean Competition Act was introduced into the United States Senate by Senator Sheldon Whitehouse in response to the EU’s internal negotiations on a CBAM. The Bill sets out a CBAM at US$55 per ton on goods with a carbon-intensive manufacturing process, including including fossil fuels, refined petroleum products, petrochemicals, fertilizer, hydrogen, adipic acid, cement, iron and steel, aluminum, glass, pulp and paper, and ethanol.

While the Bill was not passed by the Senate, its introduction is a salient example of tariffs and trade protectionism leading to further tariffs and trade protectionism around the world.

Conversely, Japan has taken a less protectionist position. On an industry-by-industry basis, producers and exporters have made the case for free trade. For example, the Japan Aluminium Association (JAA) issued a statement opposing CBAM obligations that require traders to report all GHG emissions from fuel consumption in processes involving the manufacturing of aluminium products and flue gas cleaning. They said:

"[The] content of primary and secondary aluminium are directly related to the confidential cost of each product," JAA said.

While opposition to trade barriers continues, increased emissions reduction efforts are likely to be well received. Observers will keep a keen eye on EU developments as the European Commission negotiates the final structure of their CBAM ahead of implementation beyond the transitional period on 1 January 2026. Of note will be the emissions reporting standards the EU chooses to enforce on trading partners, and whether it will ultimately calculate emissions based upon emissions of 10% of the least efficient producers in the EU in the relevant industry if it deems that emissions data is not available from the importer.

Meanwhile, Down Under

In January this year the Australian Government announced its intention to undertake a review of the suitability of a CBAM for Australia. The development of policy options and the feasibility of introducing an Australian CBAM is expected to be finalised in the third quarter of 2024[ii]. The proposed introduction of an Australian CBAM would seek to level the playing field for domestic producers that are subject to carbon pricing and the Safeguard Mechanism and who face competition from foreign producers' imported products not subject to the same rules – the emissions-intensive, trade-exposed industries (EITEIs). The Australian Workers Union has publicly thrown its support behind carbon tariffs for Chinese steel, for example, and other “dirty” imports.

Yet our own Productivity Commission has noted that there are questions about the extent to which carbon leakage will actually occur as a result of domestic climate policy.

The Commission argues that given our Safeguard Mechanism is more generous than the EU’s ETS there is doubt on the need to provide more assistance to EITEIs, which may face CBAMs, while the policy case for providing protection through our own CBAM for these industries “is not compelling” and would simply represent trade protectionism.

Globally there is an impetus for CBAMs but observers are likely to watch closely what major economies like the United States do in response to the EU’s CBAM. While the Clean Competition Act has expired, it or a similar Bill could be introduced to the Congress at any time. It is difficult to envisage global free trade continuing to experience strong growth if new barriers like this expand, and, as the Productivity Commission has noted, an Australian CBAM would risk “simply acting as a form of trade protectionism for Australian industry”.

[i] Productivity Commission, Trade and assistance review, 2021-22, page 65

[ii] See https://minister.dcceew.gov.au/bowen/speeches/speech-australian-business-economists

Related Analysis

Climate and energy: What do the next three years hold?

With Labor being returned to Government for a second term, this time with an increased majority, the next three years will represent a litmus test for how Australia is tracking to meet its signature 2030 targets of 43 per cent emissions reduction and 82 per cent renewable generation, and not to mention, the looming 2035 target. With significant obstacles laying ahead, the Government will need to hit the ground running. We take a look at some of the key projections and checkpoints throughout the next term.

Certificate schemes – good for governments, but what about customers?

Retailer certificate schemes have been growing in popularity in recent years as a policy mechanism to help deliver the energy transition. The report puts forward some recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of these schemes. It also includes a deeper dive into the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme.

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.