The costs of reliability: Handle with care

With the recent load shedding in Victoria system reliability continues to be in the headlines. Its current prominence also stems from the political debate that followed South Australia’s state wide blackout in September 2016, the closure of older firm power stations and the transition underway in energy supply as more renewable generation is introduced to the National Electricity Market. Renewable advocates highlight fossil fuel plant outages in recent peak demand periods, linking them to a long-term trend of declining performance, while the Victorian Government has used it to justify the underwriting of more renewables. In contrast, the Federal Government argues that it justifies its market intervention to underwrite firm generation.

The concept of reliability and loss of power due to insufficient supply are often misunderstood and confused with network outages and system security.

This has been recognised by two significant pieces of work released in the past week. The Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) handed down its draft determination on a proposed rule change to expand the Reliability and Emergency Reserve Trader (RERT) mechanism by which the Australian Energy market Operator (AEMO) can secure back-up reserves when it anticipates the market’s reliability may fall below the reliability standard.

The Grattan Institute report “Keep calm and carry on – managing electricity reliability” flagged the challenge of the current situation: Increasing reliability costs money and a trade-off must be made between that higher cost to end users and reliability. We need to be careful in the current sensitive political climate not to overreact to isolated issues for fear of significantly pushing up household and business electricity bills. How much consumers are willing to pay for additional reliability is the key question and one that the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) is looking at the value customers place on reliability – whether they are prepared to pay more to avoid outages during peak periods - and is expecting to release its estimates by the end of this year. Grattan found that contrary to media impressions, actual customer interruptions are progressively declining.

Both the AEMC and Grattan’s work point to the reliability standard of 99.998 per cent of forecast total energy demand in a financial year being met remaining appropriate. Grattan points to the NEM performing well within its targeted reliability standard that no more than 0.002 per cent of energy consumption should be left unsupplied in any market region due to a lack of generation or transmission capacity. 100 per cent reliability is impossible, and the reliability standard reflects the trade-off between the impact of load shedding on customers and the cost of having more generators on standby.

There are three forms of blackout or power outages that can occur:

- Reliability related: This relates to the supply-demand balance. A reliable power system will have sufficient generation, demand response and inter-state transmission capacity to meet demand. Reliability issues occur when the demand-supply balance is tight, which is most likely to be at times of peak demand such as during heatwave conditions[i]. Simply put, it is the rarest, but most easily understood circumstance of “running out of generation”. When this happens, AEMO must direct the rotational load shedding of some customers. Customers are switched off for no more than an hour at a time, and very sensitive loads, such as hospitals, are usually avoided.

- System security: a secure system is defined[ii] as being one that is able to operate within determined technical limits even if there is an incident such as the loss of a major transmission line or large generator. According to AEMC these are largely caused by sudden equipment failure which can be the result of extreme weather or bushfires, for example that can lead to voltage or frequency issues. The South Australian system black that occurred in September 2016 was a security event. Note that at the time demand was not particularly high, and there was more than adequate generation on standby. For these problems we need to focus on the integrity of the grid, not to build more generators.

- Localised outages: these can be for any number of reasons – a tree limb on a power line, a vehicle hitting a pole, equipment failure, weather event or an animal interfering with power lines usually in low voltage distribution lines. These events typically last from a few hours to potentially days, and so are typically the most inconvenient of all interruptions to customers.

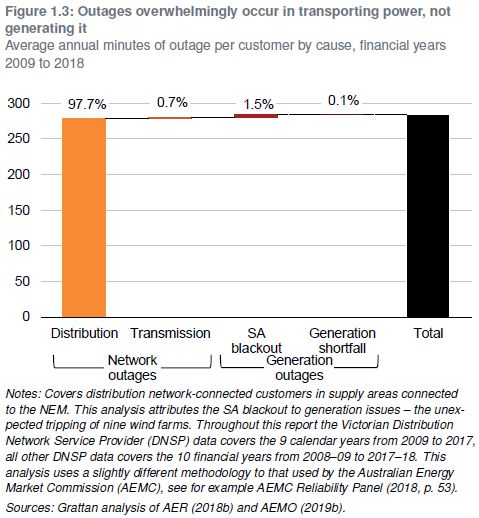

Grattan notes that only 0.1 per cent of outages in the past 10 years (to June 2018) were due to lack of supply, i.e. Reliability related. Approximately 2.2 per cent were related to system security issues (and most of these related to South Australia’s 2016 statewide blackout) and more than 97 per cent occurred due to faults in the distribution network. Figure 1 illustrates the weightings.

Figure 1: Sources of Outages: FY 2009-2018

Source: Grattan Institute, February 2019

Reliability

While in the public consciousness reliability of the power system is most in question due to media commentary, political “grandstanding” and threats of government intervention[iii] interruptions are remain extremely unusual.

In its draft determination the AEMC also comments that the extent of load shedding due to reliability has been rare. Up until 30 June 2018 there were only two reliability events in the NEM (on 29 and 30 January 2009 in SA and Victoria and 8 February 2017), subsequently there was load shedding on 24 and 25 January in Victoria, which is currently being reviewed by AEMO.

In the recent Victorian situation, while demand was short of historical records (9281MW vs 10,490MW in 2009) the conditions coincided with unit outages in the Latrobe Valley with approximately 1300MW unavailable, wind was variable and suffered reductions at critical times. Having three of the Latrobe Valley’s 10 large units on unrelated outages at the critical time is exceptional and contrasts with generally good performance at other high demand times this summer. It appears the actual outages were the result of standard random plant failures, and were not definitively related to age or the hot conditions. AEMO has recently increased their assumed forced outage rates for brown-coal plants, but even with these higher rates the probability of having three or more units out at the peak time is less than 6 per cent. We need to consider these matters rationally before investing in costly interventions: It appears that on 24 and 25 January 2018, simple bad luck was unfortunately at play.

Whilst final figures are not yet available the total amount of load shedding in Victoria appears to be at or slightly above the 0.002 per cent target. If so, it would be the first unserved energy event in Victoria for a decade and despite that there was no USE in other regions and, as the target is expressed as an average over time, the NEM continues to operate well within the standard.

AEMO sought an enhanced RERT to allow it to contract three years ahead and to apply different thresholds for its activation than the reliability standard.

In its draft determination on the proposed enhancement rule change, the AEMC said that it felt that the reliability standard remains appropriate. It did note the changing nature of the system and that “the changing characteristics of the generation fleet and increase in extreme weather events make the power system less stable, more volatile and difficult to operate”. But that this “in and of itself does not suggest that the reliability standard is no longer appropriate but does mean that the way the power system is operated to meet the standard may change”. It also considered that the current framework is flexible enough to adapt and accommodate the changes.

In its draft determination (which is now open to comment) the AEMC has proposed increasing AEMO’s contracting period for the RERT from nine to 12 months, but limits the operator from purchasing reserve beyond that necessary to achieve the reliability standard. The AEMC expects to make its final determination by 2 May this year.

Security

The focus on the security of supply has become sharper with the increased amount of intermittent, or non-synchronous, generation from wind and solar. This, as noted by the Grattan report, means that as it displaces traditional synchronous generators (coal, gas and hydro), the grid will become more vulnerable to shocks unless other steps are taken.

Synchronous generators have characteristics that support grid stability such as inertia which support frequency control.

The grid can be destabilised by weather events or natural disasters and equipment failure, such events cause about 2.2 per cent of all outages but can have significant consequences, as occurred in South Australia in September 2016.

According to Grattan their have been 70 instances of load shedding in response to sudden shocks to the high voltage grid which includes generators and transmission lines in the 10 years to June 2018. Of these 45 were due to network equipment failures, 23 by natural events like lightning strikes, bushfires or bad weather and two were triggered by generator issues.

Localised outages

These are usually caused by network interruptions and account for more than 97 per cent of customer outages. This is the result of equipment failures, failing trees, animal intrusions, lightning strikes or accidents. While these kind of uncontrollable events cannot by their nature be completely prevented, Grattan notes that Australia’s distribution networks are incrementally improving reliability over time. Excluding uncontrollable events Grattan estimates that the normalised level of outages has declined from about 133 minutes per customer between 2006-2011 and 116 minutes in in the next six years to June 2017.

New technology is assisting with the roll-out of auto-reclose devices to restore power automatically when minor line faults occur, such as a branch falling on lines. As a result total outages in Victoria have reduced by 70 per cent in less than 30 years[iv]

Grattan also noted that these outages tend, like reliability load shedding, to be more common in hot weather.

Conclusion

Grattan’s report urges caution in responding to “misperceptions” about the system’s overall reliability because over-reaction will simply add to the cost of electricity while not improving reliability significantly.

To address the closure of more coal generators and deal with more severe heatwaves will require more investment in new supply and a stable policy framework is needed to achieve this.

In terms of system security it notes that AEMO has already implemented new management practices to address the changing shape of the energy system and regulatory obligations and market mechanisms are being applied.

It notes that it would be “prohibitively” expensive to attempt to prevent all localised outages and regulators and networks need to balance the cost and reliability as weather patterns and technology and consumer preferences change.

AEMC’s draft determination is also driven by a need to balance the reliability challenge against the additional costs via an enhanced RERT.

[i] A heatwave is described by the Bureau of Meteorology as three or more consecutive days of unusually high temperatures.

[ii] AEMC, Draft rule determination, page 9

[iii] Keep calm and carry on, Managing electricity reliability, Grattan Institute, February 2019

[iv] Ibid, page 36

Related Analysis

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

The return of Trump: What does it mean for Australia’s 2035 target?

Donald Trump’s decisive election win has given him a mandate to enact sweeping policy changes, including in the energy sector, potentially altering the US’s energy landscape. His proposals, which include halting offshore wind projects, withdrawing the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), could have a knock-on effect across the globe, as countries try to navigate a path towards net zero. So, what are his policies, and what do they mean for Australia’s own emission reduction targets? We take a look.

Is increased volatility the new norm?

This year has showcased an increased level of volatility in the National Electricity Market (NEM). To date we have seen significant fluctuations in spot prices with prices hitting both maximum price caps on several occasions and ongoing growth in periods of negative prices with generation being curtailed at times. We took a closer look at why this is happening and the impact this could have on the grid in the future.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.