Price caps: “More harm than good”?

Australian governments federally and in Victoria have now unveiled price re-regulation via default market caps on prices. Meanwhile, New Zealand’s energy experts have recommended against capping retail prices, consistent with the Australian Energy Market Commission’s (AEMC) advice to COAG Energy Ministers. And KPMG analysis of the UK price cap shows that it led to a "significant" reduction in price dispersion.

The New Zealand expert panel was appointed to review that country’s electricity prices and has just released an options paper, which steers away from retail price caps, warning that they “do more harm than good and there are better ways to tackle the problems of the two-tier system”[i].

The Electricity Price Review - Options Paper notes that while price caps can directly target “excessive” electricity prices, “regulation this prescriptive has risks. If a price cap is set too high, retailers may charge excessive prices. If set too low, retailers may be unwilling to supply electricity because they can’t cover their full costs. Price regulation can also cause longer-term harm by stifling innovation”.

The panel highlights that setting price caps and getting them right is challenging because of the large volume of information needed and the dynamic aspect of inputs like wholesale prices.

It is a similar red flag to that hoisted by the AEMC when advising COAG energy ministers on default tariffs in December.

The AEMC in its advice noted that while a default would benefit a minority of retail customers (around 14 per cent, which it expects to fall to around 10 per cent in the next couple of years), it risks damaging competition and with it the cheaper market offers that the vast majority of households currently enjoy. It also commented that analysis across its retail energy competition reviews has consistently shown that jurisdictions with price regulation “experience lower price dispersion than those without price regulation”.

It points to the United Kingdom’s experience - where the gap between the regulated cap and the market deals has narrowed - to support its claim.

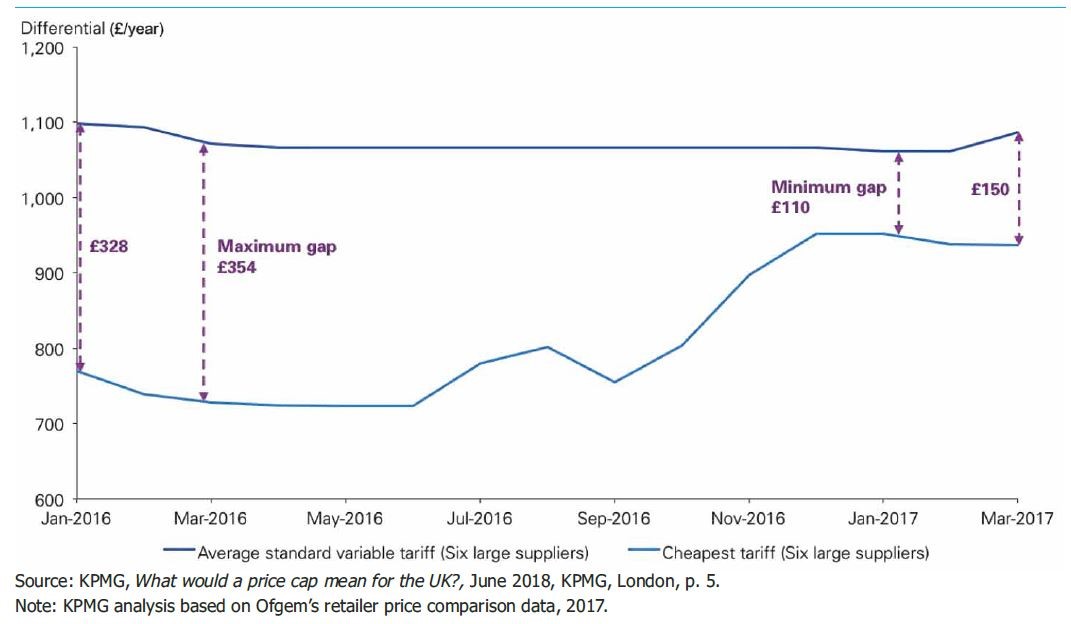

- The UK’s experience in re-introducing price regulation through a temporary default offer cap led to price compression. Following the announcement of the default cap in June 2016, a significant reduction in price dispersion has occurred in the UK as the price of the cheapest deals increased.

- KPMG undertook analysis of the reaction of the six largest UK retailers to the proposal, shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Analysis of changes in retail prices in the UK

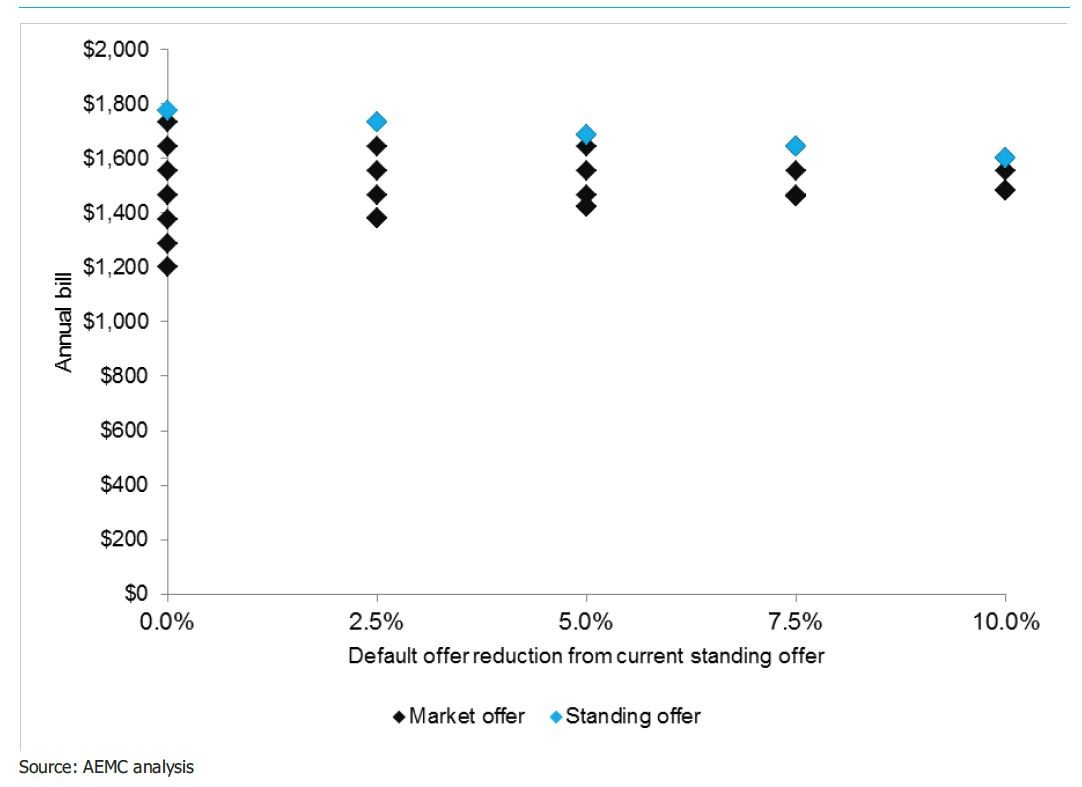

The AEMC also illustrate the potential impact if retailers sought to recover 50 per cent of the revenue lost from a default price cap. Figure 2 below shows the potential impact for NSW at various default price settings.

Figure 2: Range of offers under default offer - New South Wales

It shows that a default offer set 10 per cent below the current average standing offer could result in a 23.6 per cent increase in the lowest market offer bills.

In South Australia, a default offer set 10 per cent below the current standing offer price would increase the lowest market offers by 25.8 per cent. For South East Queensland (SEQ), convergence occurs faster than South Australia and New South Wales.

The AEMC flags that for SEQ, a default set at 10 per cent the current average standing offer, the only way for retailers to recover half their revenue loss would be to set market offers above the default, which is obviously not viable. A default set at 5 per cent under the current standing offer would mean a 30.8 per cent increase in the best market offer available.

It also found a default price cap would create a number of risks, such as:

- An increase in prices for at least some customers on market offers;

- An increase in standing offer prices that are currently set below the new cap;

- A decrease in the range of offers available in the market;

- Lower levels of innovation as “discounts off the standing offer” become the most common offer; and,

- Higher barriers to entry for new retailers, as well as changes in consumer behaviour, resulting in decreased competition in the energy retail market and ultimate higher average prices for consumers.

Across the Ditch

New Zealand’s assessment of its electricity prices was undertaken by an expert eight-member advisory panel, which was appointed in April last year. The panel is chaired by Miriam Dean, who was a member of the 2009 review of the electricity market, but also brings an extensive legal background.

The catalyst for the review was similar to that in Australia - electricity prices, especially for households, had increased faster than inflation for many years, although it notes that prices faced by commercial and industrial customers have remained relatively flat.

In particular, it was tasked with assessing whether the electricity market was delivering “a fair and equitable price to end-consumers”. For the first time the terms of reference required the panel to consider the need for electricity prices to be “fair and affordable, not just efficient or competitive”.

As with Australia while New Zealand has experienced growth in retail competition it has also identified a “two-tier market” where customers who are prepared to shop around get better deals, while those who don’t end up paying higher prices than they would otherwise. Overall though the panel favours ways to increase competition further and give customers more access to information rather than cap prices.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.