New Zealand demand and generation scenarios

Much like Australia, the closure of thermal generation to reduce CO2 emissions has been a key part of New Zealand’s energy transformation. A recent forecasting report by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) predicts that over 3,000 MW of geothermal and wind generation capacity will be built between now and 2040. Despite New Zealand’s move to reduce CO2 emissions there have been issues with security of supply, due to the closure of firm generation and the increase in the uptake of wind. Subdued growth in residential and commercial electricity demand has also had an impact and is expected to continue, which is likely to impact the life of the firm generators.

New Zealand generation transformation

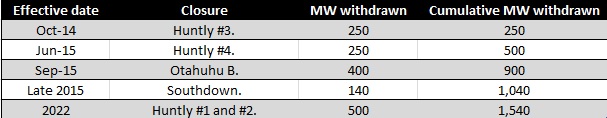

The gradual closure of thermal generation across New Zealand is shown in Table 1. In 2014, 79.9 per cent of electricity generation came from renewable resources, increasing from 75.1 per cent in 2013[i].

Table 1: The loss of generation capacity

Source: Pipes & Wires, Insight and Analysis of Cool Energy and Infrastructure stuff, Issue 156, September 2016

The ‘Electricity Demand and Generation Scenarios’ (EDGS) report, published by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) in August 2016 shows that the percentage of electricity generated from renewable sources is forecast to grow to meet increasing demand across all scenarios. The ‘Global Low Carbon’ and ‘Mixed Renewables’ scenarios are used[ii]. The Mixed Renewables contains a mixture of geothermal and wind plants built from 2020 onwards, and the Global Low Carbon scenario contains high carbon price and lower renewable cost leads to more renewable build assumptions.

It is expected that New Zealand will have 790 MW and 2,530 MW of new geothermal and wind capacity built respectively between now and 2040. The report claims that wind and geothermal plants are the cheapest to build and have a long run marginal cost (LRMC) ranging from $80 to over $100 per MWh. The forecasts assume the closure of New Zealand’s only aluminium smelter scheduled for 2018 and the retirement of the remaining large coal-fired generators. The report also emphasises the prediction that there will be higher uptake of electric vehicles (EVs) which could be met by solar photovoltaic (PV) with batteries, wind and geothermal.

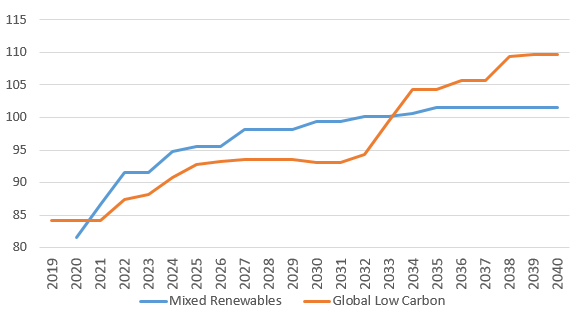

In the Global Low Carbon scenario, 90 per cent of renewable generation will be reached by 2020, while roughly 85 per cent will be reached under Mixed Renewables scenario. Figure 1 provides wholesale electricity price indicators under two different scenarios, assuming lower cost plants are built first in each case[iii]. It can be seen that the wholesale electricity price increases as more expensive plants are built. Under the Global Low Carbon scenario, prices increase at a lower rate than in the Mixed Renewables scenario at the start of 2020, partly because of the lower marginal cost of new wind generation.

Figure 1: Wholesale electricity price indicator (NZ$/MWh in real 2013 prices)

Source: Electricity demand and generation scenarios, August 2016

Despite forecasts suggesting New Zealand’s transformation to wind and geothermal, a recent announcement by Genesis Energy and other electricity generators stated that they will extend the operational life of their coal and gas fired stations. Rankine Units at the Huntly Power Station have entered into contracts which will keep the two coal/gas stations available to the electricity market until December 2022, an extension of the previously announced closure date of 2018[iv].

There are various reasons which could be attributed to this announcement. One includes the issue of system security which was recently assessed in a review of Transpower’s 2016 Security of Supply Annual Assessment[v]. The report reveals the following conclusions:

- The key system security measures would fall below the security standard in the winter of 2019 if the announced closure of the two Huntly generators were to actually occur in late 2018;

- The measures would continue to be lower than the security standard until beyond 2025 unless there is further generation investment; and

- The winter security measures were lower in the 2016 Assessment than they were in the 2015 assessment due to the Southdown closure and the proposed Huntly closures[vi].

With the Tiwai smelter likely to continue operating, this could be a focal point for deciding whether generators such as Huntly should remain open. In recent years, relatively flat growth in consumer and industrial demand for electricity have led to the retirement of numerous coal plants.

Energy demand in New Zealand

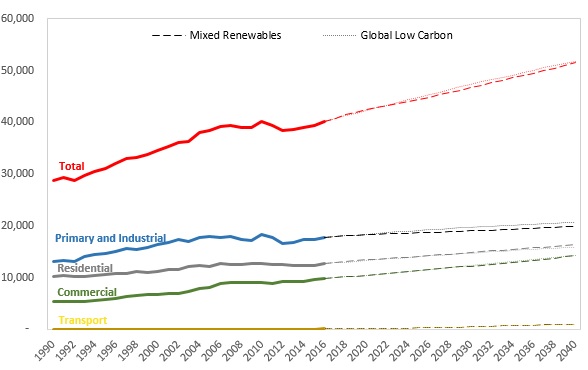

Figure 2 provides an outlook for electricity demand since 1990. Between 1990 and 2004, electricity demand increased rapidly, growing by over 2 per cent per annum on average as a consequence of strong growth in the economy and population[vii]. Since then, electricity demand growth has slowed to an average of only 0.5 per cent per annum.

Figure 2: Consumer electricity demand by Sector from 1990 (GWh)

Source: Data from Electricity demand and generation scenarios, August 2016 / Australian Energy Council analysis, September 2016

Assuming the same GDP and demographic, electricity demand in the Global Low Carbon scenario is higher than in the Mixed Renewables scenario for the majority of the 2020s and 2030s. The high carbon price assumption (under the Global Low Carbon model) causes a fuel-switch from high carbon intensive fuels to electricity, especially in the primary and industrial sectors (see Figure 2). Also, assuming EVs will eventually become economic, “increasing to over 40 per cent of new cars by 2040”[viii], there would be an increasing demand in electricity under Global Low Carbon scenario. Residential and Commercial electricity demand have the same growth under the two scenarios.

[i] Energy in New Zealand 2015, Ministry of business, Innovation & Employment

[ii] Electricity Demand and Supply Generation Scenarios 2016, Ministry of business, Innovation & Employment

[iii] Electricity Demand and Supply Generation Scenarios 2016, Ministry of business, Innovation & Employment, page 18

[iv] Genesis Energy media release, 2016, “Rankine units operational life extended”

[v] Transpower, 2016, “Security of Supply Annual Assessment 2016”, https://www.transpower.co.nz/sites/default/files/bulk-upload/documents/SoS%20Annual%20Assessment%202016.pdf

[vi] ibid

[vii] New Zealand’s Energy Outlook Electricity Insight, Ministry of business, Innovation & Employment

[viii] New Zealand’s Energy Outlook Electricity Insight, Ministry of business, Innovation & Employment, page 7

Related Analysis

International Energy Summit: The State of the Global Energy Transition

Australian Energy Council CEO Louisa Kinnear and the Energy Networks Australia CEO and Chair, Dom van den Berg and John Cleland recently attended the International Electricity Summit. Held every 18 months, the Summit brings together leaders from across the globe to share updates on energy markets around the world and the opportunities and challenges being faced as the world collectively transitions to net zero. We take a look at what was discussed.

Great British Energy – The UK’s new state-owned energy company

Last week’s UK election saw the Labour Party return to government after 14 years in opposition. Their emphatic win – the largest majority in a quarter of a century - delivered a mandate to implement their party manifesto, including a promise to set up Great British Energy (GB Energy), a publicly-owned and independently-run energy company which aims to deliver cheaper energy bills and cleaner power. So what is GB Energy and how will it work? We take a closer look.

Delivering on the ISP – risks and opportunities for future iterations

AEMO’s Integrated System Plan (ISP) maps an optimal development path (ODP) for generation, storage and network investments to hit the country’s net zero by 2050 target. It is predicated on a range of Federal and state government policy settings and reforms and on a range of scenarios succeeding. As with all modelling exercises, the ISP is based on a range of inputs and assumptions, all of which can, and do, change. AEMO itself has highlighted several risks. We take a look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.