Ireland’s new “Integrated Single Electricity Market”: Any lessons for the NEM?

Written by Peter Carruthers, Terry Grimwade and Brendan Ring from Market Reform, a consultancy firm specialising in energy market reform programs. Each author has spent over two years on the I-SEM Project in various roles including market design, rules development and market implementation.

Ireland’s wholesale electricity market, encompassing both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, has recently undergone a major reform project that started in 2014 and delivered a new “Integrated Single Electricity Market” (I-SEM), going live in October 2018.

The Irish market serves a population of approximately 6.8 million people, with total annual delivered energy of about 38TWh. By comparison, Victoria has a similar population (6.5 million) and electricity consumption of 47TWh.

Renewable energy currently meets about 35 per cent of annual energy demand in Ireland, primarily from onshore wind. This has grown from about 12 per cent in 2010 on the back of European renewable energy directives. The Republic of Ireland is now targeting 70 per cent supply via renewables by 2030, to be supported through a new Renewable Electricity Support Scheme (RESS).

The new Irish market introduced a Day-Ahead and Intraday market, a new balancing market and a capacity market. In parallel, to support the ambitious renewable energy targets, a range of ancillary services functions have been implemented.

Some consideration of the I-SEM reform process and the features of each of these new markets in Ireland may be instructive for Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM) given the review being undertaken by the Energy Security Board for the COAG Energy Council, with the aim of developing advice on a long-term, fit-for-purpose market framework to support reliability from 2025.

Drivers for the I-SEM Project

A competitive wholesale electricity market has operated in Ireland since 2007, known as the Single Electricity Market (SEM). Similar in principle to the NEM, it includes a gross pool based on a single round of bidding for energy each day, a real-time market clearing price each half hour and with retailers being price takers. A capacity market existed, with capacity payments made based on declared availability. Flows of electricity across two 500 MW HVDC interconnectors with Great Britain were based on physical capacity reservations and a trading approach, somewhat akin to the contract carriage regime we see in Australia for gas pipelines.

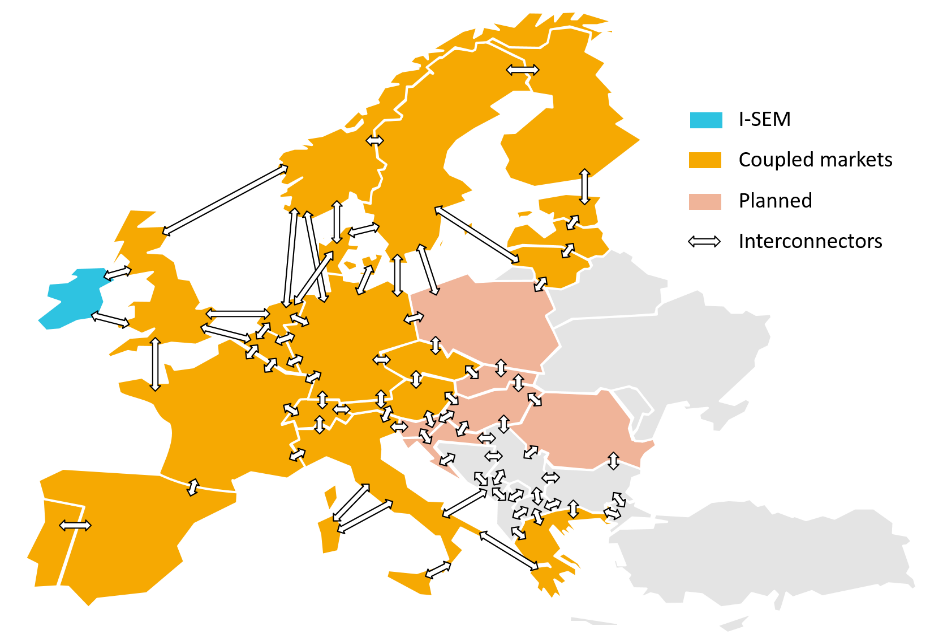

Figure 1: Ireland is physically connected to Europe via Great Britain

The key drivers for change and the goals of the I-SEM project were:

- Compliance with, and efficient implementation of, the European Union target model obligations into Ireland[i];

- Improvements to current market operations, in particular the rational and more efficient use of the interconnector capacity with Great Britain, particularly with increasing wind generation in Ireland;

- Greater participation and opportunities for trading, hedging and arbitrage and,

- Improved security of supply, transparency and integration of the market with system operations.

Market Components

The I-SEM market design is comprised of a number of inter-related markets which are outlined below:

Day-Ahead and Intraday Markets

The Day-Ahead market is a pan-European trading market designed to facilitate greater integration of European markets and more efficiently allocate electricity flows across Europe. Ireland is required to integrate into this market. The Day-Ahead market operates every day and closes at midday, 12 hours ahead of the trading day commencement. Retailers, generators and demand-side participants submit bids and offers into a double-sided auction for supply and demand. In contrast to the NEM, retailers bid their customer load into the auction process. Interconnector flows are scheduled based on the regional prices and interconnector capacities. Based on their cleared bids and offers in the Day-Ahead Market, generators and retailers will establish an aggregate net position to buy or sell a quantity of energy in each trading period for the day at the Day-Ahead market clearing price.

Financial transmission rights to hedge against inter-region price differentials caused by congestion are available, and typically procured by those participants wishing to hedge their cross-border exposures between Ireland and Great Britain. This is common, as a number of participants are active on both sides of the Irish Sea.

Intraday Market

After closure of the Day-Ahead Market, there are three intraday auctions and a facilitated continuous local market trading through which participants can trade up to an hour before each 30 minute real time trading period. The intraday markets collectively enable participants to adjust their position closer to real-time. This is most typically utilised when a participant does not establish their desired technical or commercial position in the day-ahead market, to respond to changes on the system (such as outages) and/or to respond to changes in supply (eg wind) or demand forecasts.

Linking the Day-Ahead & Intraday Markets with the Balancing Market

A participant’s final aggregated traded position in the Day-Ahead and Intraday markets represents a financially binding commitment and is actually cleared and settled daily, independently of real time outcomes. The core concept of this is similar to the day-ahead scheduling arrangements in the WEM.

This offers the participant the opportunity to set their position ahead of real-time, and therefore:

- Schedule plant accordingly – this is particularly important for demand-side participants.

- Limit financial exposure to on-the-day occurrences.

- Trade any residual or opportunistically around that position.

Participants are required to submit minute by minute physical notifications (PNs) based on their Day-Ahead and Intraday traded positions – initially after closure of the Day-Ahead Market but updated to reflect trading in the Intraday Market, or any change in their physical capabilities. Gate closure is fixed one hour prior to real time dispatch.

Balancing Market

In real time, the system operator schedules and dispatches relative to participants’ physical notifications.

As for the WEM balancing market, participants have the opportunity to offer bids and offers to adjust their physical notification. The system operator will accept these bids/offers from participants on a least-cost basis to support balancing energy or manage system constraints. A balancing market clearing price is established accordingly. The balancing market determines prices every 5 minute dispatch period, but an average of the 5 minute prices is used to calculate the 30 minute settlement price for each trading period.

A participant’s actual real time deviations from its final aggregated ex-ante traded energy position are settled and cashed out for each 30 minute trading period at the balancing market clearing price.

Capacity Market

The pan-European target model does not include a capacity market. However, in Ireland, there was a pre-existing capacity payment mechanism and the regulators determined that an enhanced capacity market, or “capacity remuneration mechanism” (CRM), was required to reduce the cost of funding capacity.

In the long term, the intention is to conduct annual auctions four years ahead (called T-4 auctions). However, a number of single year auctions (T-1) will be run for a transitional period, with capacity being awarded for 1 year for existing capacity and for up to 10 years for new capacity.

The capacity auctions procure capacity on a “de-rated basis” that reflects the marginal contribution of a one more unit of that technology maintaining the annual reliability of the power system for the year that the capacity is procured for. For example, a gas-fired unit may get de-rated to 90 per cent of installed capacity, whereas a wind unit may get 10 per cent. There is a qualification process to determine the nature of each capacity market unit and all qualified capacity, other than intermittent and new resources, must bid into the auction.

The capacity market results in successful participants being awarded “reliability options”. In return for a firm payment for their auction capacity, the capacity provider is required to return to wholesale customers (via the market operator) energy revenues (across all markets) earned above a regulatory set strike price (currently about €500/MWh) on their capacity obligations. The capacity obligations vary across time and may equal their auctioned capacity at peak times but will be lower at other times when demand is less.

Capacity providers can be left financially exposed if not running at the time the strike price applies, though the market does cap their exposure over time. These caps do mean that reliability options may not fully hedge wholesale customers above the price cap, with this cost socialised across consumers.

I-SEM Performance to Date

The I-SEM arrangements went live in October 2018. So what are the early outcomes and issues that have emerged?

Day-Ahead/Intraday Markets

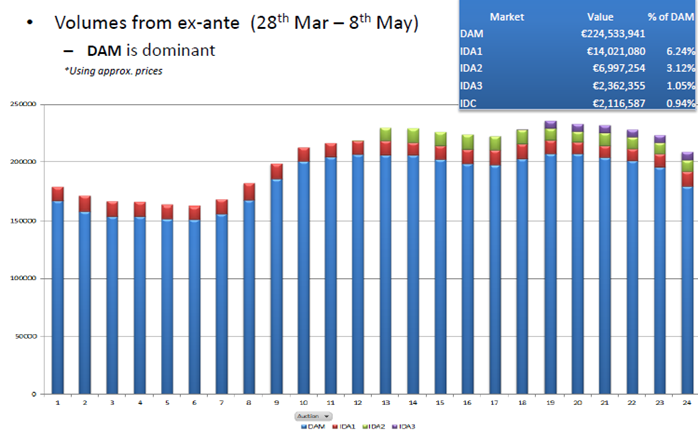

The Day-Ahead/Intraday markets have performed reliably with healthy volumes of trading in the Day-Ahead Market, and a gradually increasing volume of trading in the intraday markets (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Traded Volumes in Day-Ahead and Intraday Markets

Retailers are securing around 95 per cent of their demand through the Day-Ahead market, leaving around 5 per cent of their load exposed to the balancing market.

Market prices have appeared to be rational, and explainable based on supply and demand conditions with intraday prices increasing nearer to real time. Prices have ranged from 0–€300/MWh, and averaged €72/MWh (around A$116/MWh).

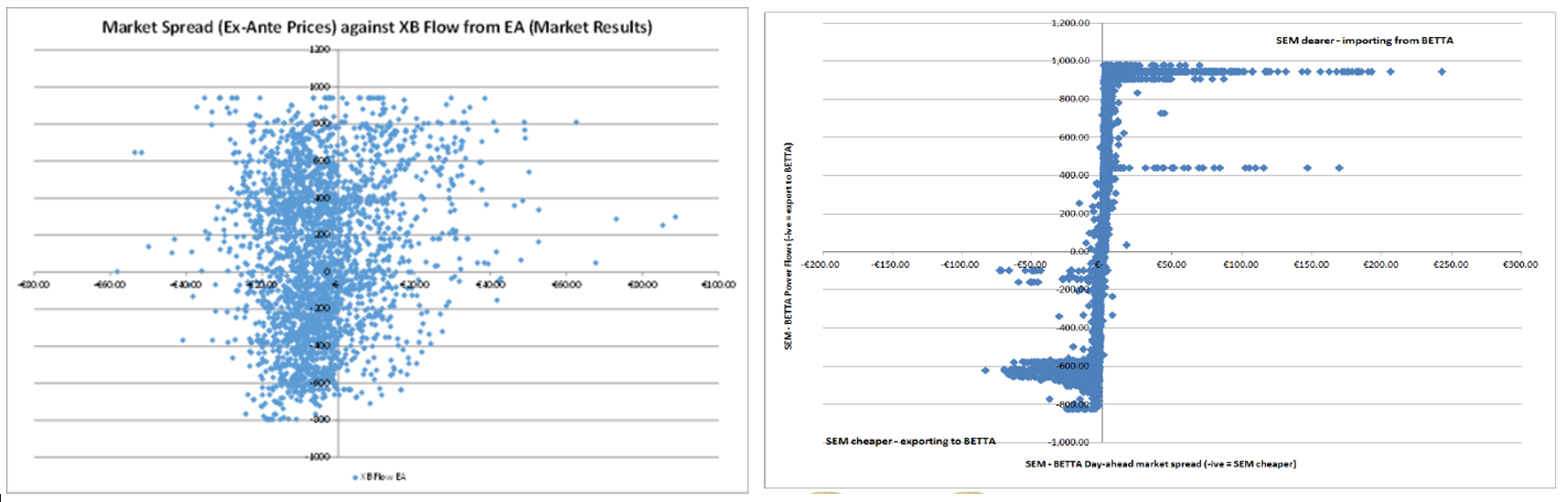

Importantly, the volumes of trading across the interconnectors with Great Britain are far more rational, based on price differences across the interconnectors, than prior to the I-SEM (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Interconnector Flows Before and After I-SEM Go-Live

Balancing Market

While a simple concept and capable of relatively simple implementation, in the case of I-SEM there were significant complexities introduced into the balancing market pricing mechanism. Many of these stem from a desire to set a single clearing price which is based purely on energy balancing actions, i.e. bids or offers that are called on purely to balance energy, rather than to deal with system constraints. For example, intra-regional congestion is managed as a system constraint. To some extent, such a separation is largely artificial but the I-SEM design went to some lengths to implement complex mechanisms that attempt to separate out and exclude from the pricing algorithm, bids and offers that are accepted for the purpose of managing constraints.

Participants have struggled to understand some of these complexities and IT vendors have struggled to deliver the required system functionality reliably.

Since market start, balancing market prices have ranged between -1000€/MWh (the price floor) and 5636.62 €/MWh for 5-minute periods, equating to -238€/MWh and 3773.69€/MWh for the 30- minute settlement prices.

While the volatility and range of prices has not, of itself, been a cause for concern, the price outcomes have at times been counter-intuitive. For example, the high price of 3773.69€/MWh was set by a constrained on peaking unit when, overall, the market was long.

The regulatory authorities have since implemented an urgent rule change to remove a number of the complex “system operator flags” in the pricing algorithm to address this and are pursuing further modifications to simplify the pricing algorithm and make it less volatile.

Capacity Market

There have been two T-1 and one T-4 auctions to date. The first T-1 auction highlighted some issues and resulted in inadequate capacity being successful in the auction to manage a specific local constraint in the Dublin area. Judicious resetting of the desired price/capacity curve and resetting of constraint limits by the regulators successfully addressed his in the second T-1 auction, perhaps indicating the ability of regulatory intervention to manipulate the capacity market outcomes.

In the first T-4 auction, there was initially no capacity cleared based on the price/capacity curve. The total capacity procured was reduced from existing levels by covering constraints first and then only clearing any further capacity is this improved the net benefit.

On the strength of the first T-4 auction, the cost of capacity to consumers has been reduced. However, it is too early to assess whether this is sustainable.

Under the reliability options, some generators have also found themselves exposed to the strike price with no possibility of being scheduled, even though they were available – the regulators are now looking to address this.

Another limitation is that the capacity auction does not yet consider renewable targets, or the mix of capacities required to support those targets.

Renewable Energy Penetration and Managing System Security

Ireland’s renewable energy targets set substantial challenges for managing system security.

A system non-synchronous penetration (SNSP) limit has been set to limit zero inertia generation as a percentage of the total. An SNSP of 75 per cent would be required to support the renewable target for 2020. The initial SNSP was 50 per cent, it is now 65 per cent and a trial of 70 per cent is soon to commence.

Ireland’s Secure, Sustainable Electricity System (“DS3” ) process procures a range of 14 ancillary services – including various reserves, frequency response and inertial response – through a mix of regulated tariffs and pay-as-bid procurement process which incentivise the development of capabilities to help support high levels of intermittent resources and resources that do not produce inertia (wind, solar, batteries, HVDC interconnectors).

Conclusion

The I-SEM market design process was led by the Irish Regulatory Authorities and a highly consultative approach was taken. Development of the Rules and market implementation was led by the Market/System Operator, again with a highly consultative approach. Overall, this was an effective approach, although the cautionary note is the need to monitor complexity levels carefully. In particular, complexity in the balancing market caused implementation difficulties across the industry for perceived limited gains.

Whilst the challenges facing the Irish wholesale electricity market were by no means identical to the challenges facing the NEM, similarities do exist and certainly the solutions implemented offer the potential for a great learning opportunity for the Australia’s NEM post-2025 design process.

[i] European Union Third Energy Package including Directive 2009/72/EC and Regulation (EC) No 714/2009

Related Analysis

International Energy Summit: The State of the Global Energy Transition

Australian Energy Council CEO Louisa Kinnear and the Energy Networks Australia CEO and Chair, Dom van den Berg and John Cleland recently attended the International Electricity Summit. Held every 18 months, the Summit brings together leaders from across the globe to share updates on energy markets around the world and the opportunities and challenges being faced as the world collectively transitions to net zero. We take a look at what was discussed.

Retail protection reviews – A view from the frontline

The Australian Energy Regulator (AER) and the Essential Services Commission (ESC) have released separate papers to review and consult on changes to their respective regulation around payment difficulty. Many elements of the proposed changes focus on the interactions between an energy retailer’s call-centre and their hardship customers, we visited one of these call centres to understand how these frameworks are implemented in practice. Drawing on this experience, we take a look at the reviews that are underway.

Great British Energy – The UK’s new state-owned energy company

Last week’s UK election saw the Labour Party return to government after 14 years in opposition. Their emphatic win – the largest majority in a quarter of a century - delivered a mandate to implement their party manifesto, including a promise to set up Great British Energy (GB Energy), a publicly-owned and independently-run energy company which aims to deliver cheaper energy bills and cleaner power. So what is GB Energy and how will it work? We take a closer look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.