Generator rebidding: Fair game for criticism?

The electricity market has been under intense public and political scrutiny for some time. In July this year electricity generators in particular were put under the microscope because of claims that they were “gaming” the market through rebidding, which was costing consumers millions of dollars.

Despite denials by companies operating in the National Electricity Market (NEM) and previous reviews of high price events not pointing to similar claims, the matter was referred by the-then Energy Minister, Josh Frydenberg to the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC).

Last week the AEMC handed down its final report. The overall verdict is that there is not an issue with the rebidding provisions of the NEM and the attributing $825 million out of the $18 billion wholesale turnover from 2015 to 2017 as a result of generator gaming was exaggerated because the definition of gaming that was used was too broad.

Instead it found that more routine (and mundane) factors were behind most of the increased volatility between 2015 and 2017, unrelated to rebidding. This was a combination of actual demand differing from forecast demand, and issues with generator availability as a result of factors such as units tripping.

Mostly Working

At the beginning of July the Grattan Institute released a report, “Mostly working: Australia’s wholesale electricity market”.[i] The report considered a 130 per cent increase in wholesale power prices between 2015 and 2017 (with the price paid for power going from $8 billion to $18 billion) and correctly attributed the majority of the rise to:

- the closure of “big, old, low-cost” coal-fired power stations (Northern in South Australia in 2016 and Hazelwood in Victoria in 2017). This accounted for $6 billion of the increase

- the price of key inputs, especially gas and black coal, rising just when the plants they fuel were needed more often. This accounted for $4 billion.

It is extremely difficult to quantify the cause of a price change in any market, let alone something as complex as the NEM, so such values should be treated cautiously. Nevertheless, the Energy Council would agree that these issues clearly were the main causes of price increases during the period studied.

The report then went on to allege that major electricity generators were ‘gaming’ the system by using their power in a concentrated market to create an artificial scarcity of supply. It put an $800 million cost on late bidding in both 2016 and 2017. It also pointed to Queensland making up two-thirds of the cost and suggested that the cost of this increased by $250 million between 2015 and 2017.

In turn it said factors that contributed to gaming were a high concentration of generation ownership, heavy reliance on generation that could not respond quickly and, finally, the rebidding rules. It recommended that a gate closure mechanism be introduced to address rebidding.

Because it added fuel to an already overly intense political fire around energy prices, the “gaming” claim obscured the central point of the report: higher prices caused by the other factors were the “new normal” and government should be telling the public this harsh truth.

The media unsurprisingly latched onto the gaming claim: On 2 July The Australian newspaper reported, “Gaming by generators pushing up power bills”, while the Australian Financial Review’s headline stated: “‘Unacceptable’: Energy grid ‘gaming’ cost Australian consumers $3.4 billion”.

In response, the Energy Minister Frydenberg called on the AEMC to assess the extent of gaming.

What did the AEMC find?

The price tag of $825 million out of $18 billion wholesale turnover from 2015 to 2017 caused by “generator gaming” was shown to be a major exaggeration. It found the definition used was too broad and as a result “inadvertently” put this label on instances of price volatility and rebidding.

The AEMC replicated the analysis using “more granular” data – that is the AEMC went into more detail by carefully considering each event against the AER’s events register. The register lists 14 potential factors for changes in price, of which rebidding is but one.

This more forensic look by the AEMC determined that $243 million of the reported price events in 2017, the AER had listed rebidding as the primary cause, as opposed to the $825 million attributed to this factor in the Grattan report. It also noted that the cost of price events for which rebidding was the primary factor has dropped since 2015, not increased.

When considering the $243 million attributed to rebidding - $214 million occurred in Queensland with virtually all occurrences happening in January and February 2017, while Queensland was experiencing heatwave conditions.

The cost of price events in which rebidding was the cause represents only 1 per cent of the wholesale cost of energy in the NEM in 2017 and while small this cost was unlikely to be passed through to consumers because retailers enter hedge contracts to prevent volatility and short-term shifts in prices being passed onto the customer. It also makes no allowance for the benefits that rebidding has in lowering wholesale prices. The AEMC report contains examples of how the rebidding process will help reduce wholesale costs[ii].

The AEMC also assessed the value of considering gate closure arrangements. It noted that it has considered bidding arrangements in the NEM “at great length” both for the Bidding in good faith rule which came into effect on 1 July 2016 and, more recently, its five minute settlement rule (2017).

The AEMC considers that the bidding in good faith rule is a more efficient means of dealing with rebidding rather than a gate closure mechanism.

Rebidding to Rise

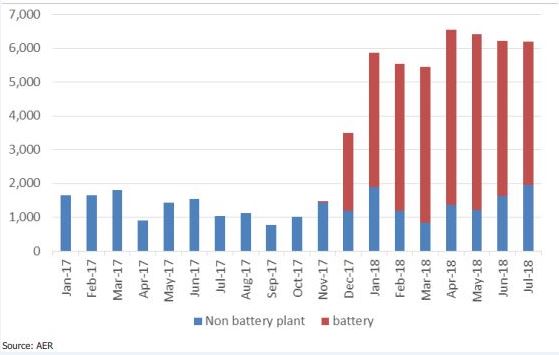

Regardless of recent events rebidding continues to have an important role to play and the AEMC notes that it expects rebidding to increase as an increasing number of new participants with flexible and fast response technologies coming into the market. Data for the Hornsdale battery in South Australia demonstrates, AEMC notes, the importance of the rebidding process to new fast response technology (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Late bidding in South Australia showing contribution of Hornsdale battery

Source: AEMC, Sept 2018

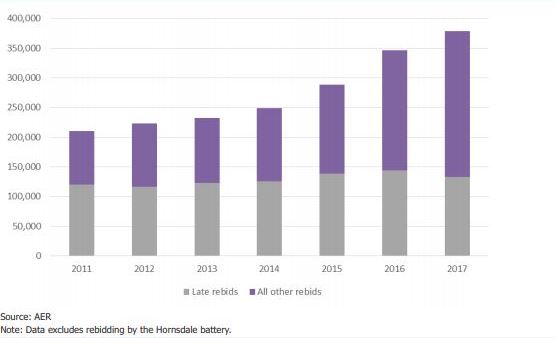

It also notes that late rebidding is not on the rise, despite the growth in rebidding generally (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Number of late rebids by year

Source: AEMC, Sept 2018

It did find that to the limited extent that bidding and rebidding behaviour in the market may be seen to be a problem, the analysis shows that they are driven by high levels of market concentration but notes that recent trends in generation investment, as well as the proposed establishment of CleanCo by the Queensland Government to create a third government-owned generator, may help alleviate the concerns.

Conclusion

The Grattan report into the wholesale costs correctly identified the majority of the increase in total wholesale costs from $8bn to $18bn from 2015 to 2017 as being caused by the closure of coal-fired plant and the increase in key fuel costs. In fact the major conclusion of the report was that the market was “largely working” as intended. However despite this, the report’s identification of “gaming” was always going to attract media interest, which it did, and which in turn led the government to have the market regulators unpick the report.

This analysis concluded that the report effectively allocated all periods of volatility to “generator gaming”, while AER analysis showed that all but $243 million of the $825 million were events of volatility that the AER had already determined were caused by other factors, such as inaccuracies in the demand forecasts and changes in generator availability and network constraints.

Of the $243 million of costs that were potentially affected by generator rebidding, $214 million occurred during January and February 2017 in Queensland. There is clearly no evidence of widespread misuse of the NEM’s bidding provisions to push up prices, which is a view that was previously corroborated in the AER’s report into NSW pricing events[iii].

The AEMC has provided a clear explanation of how the NEM’s bidding provisions are an important mechanism to achieve an efficient and reliable market, matters which have been looked into many times previously. Generator freedom to rebid is an important enabler of competition and overall leads to lower prices.

[i] Mostly working: Australia’s wholesale electricity market report, Grattan Institute, 1 July 2018, https://grattan.edu.au/report/mostly-working/

[ii] Gaming in rebidding, Final Report, AEMC, 28 September 2018, page 18, https://www.aemc.gov.au/sites/default/files/2018-10/Final%20report.pdf

[iii] AER electricity wholesale performance monitoring: NSW electricity market advice report, AER, Dec 2017, https://www.aer.gov.au/system/files/NSW%20electricity%20market%20advice%20-%20December%202017_0.PDF

Related Analysis

Principles-based regulations: What are the opportunities and trade-offs?

As Australia’s energy market continues to evolve, so do the approaches to its regulation. With consumers engaging in a wider range of products and services, regulators are exploring a shift from prescriptive, rules-based models to principles-based frameworks. Central to this discussion is the potential introduction of a “consumer duty” for retailers aimed at addressing future risks and supporting better outcomes. We take a closer look at the current consultations underway, unpack what principles-based regulation involves, and consider the opportunities and challenges it may bring.

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

Is increased volatility the new norm?

This year has showcased an increased level of volatility in the National Electricity Market (NEM). To date we have seen significant fluctuations in spot prices with prices hitting both maximum price caps on several occasions and ongoing growth in periods of negative prices with generation being curtailed at times. We took a closer look at why this is happening and the impact this could have on the grid in the future.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.