Copenhill waste-to-energy plant: How hot is it?

Integrating new energy technology has taken on a new meaning in Denmark. Copenhageners will be able to ski the capital’s first slope when the €500 million Amager Resource Centre – a waste-to-energy (WtE) plant - opens later this year.

Danish architecture firm Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) promises to turn the plant, nicknamed Copenhill by locals, into a popular attraction.

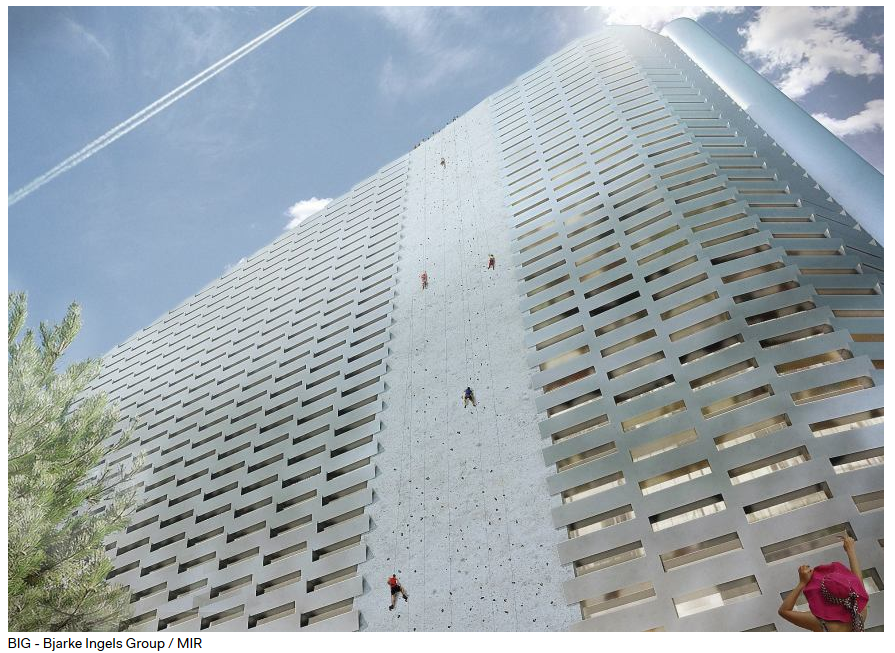

It will open to the public with an artificial 600-meter ski slope, tree-lined recreational hiking and running trails, the world’s tallest artificial 86-meter-high climbing wall, a viewing and picnic plateau, and full-service café - all atop the plant. While facilities for water sports, soccer fields and a go-kart track will lie around the facility.

Figure 1: Render of plant once completed

Source: Babcock & Wilcox Vølund A/S

Source: Babcock & Wilcox Vølund A/S

Waste to energy growth

European interest in WtE plants has accelerated since 1999, when the European Union directed member states to minimise the amount of waste going to landfills. In Norway the sector has been growing for the past decade, increasing from a total capacity of about 1 million tonnes/year to 1.7 million tonnes today[i].

According to CenBio[ii] energy recovered from waste currently represents the main energy source of the Norwegian district heating system, having more than doubled to around 5 TWh/year since 2009. It also highlights that half of the energy from WtE is considered renewable in Norway’s national statistics, and the sector is contributing to the national renewable energy target.

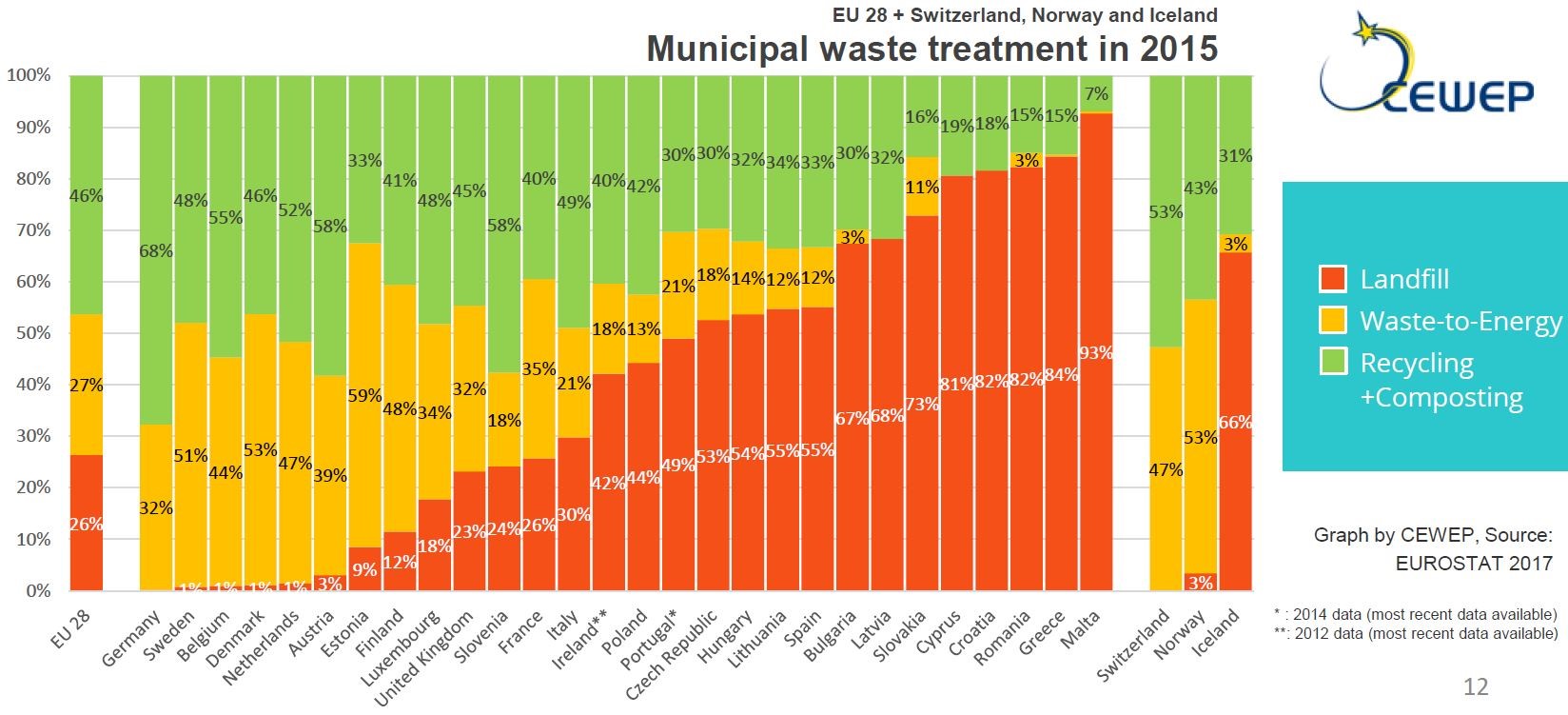

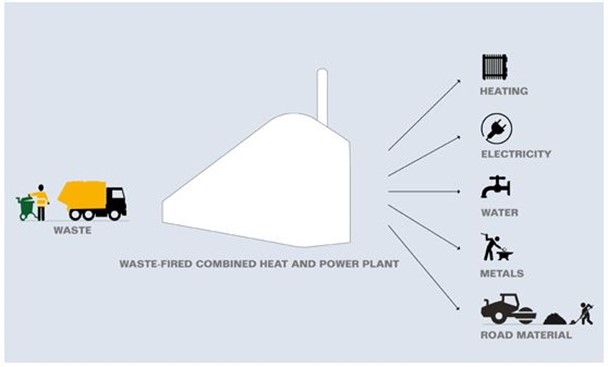

Figure 2 shows the extent of WtE plants in Norway, as well as the EU, Switzerland and Ireland. Norway has one of the highest rates of converting WtE. Figure 3 shows the process in a typical WtE plant.

Figure 2: Recycling and WtE complementary to divert waste from landfills

Source: Confederation of European Waste to Energy Plants

Figure 3

Source: Deltaway Energy

Source: Deltaway Energy

Copenhill Design

The approach at Copenhill is to integrate the WtE plant with the local community and to try and “shift the perception of what a utility can be”. The plant is located on an industrial island in the outskirts of Copenhagen. BIG recognised that in recent years the area had attracted adventure sports enthusiasts with cable wake boarding, rock climbing and windsurfing. So instead of designing a stand-alone plant, the group proposed “a new breed of WtE plant” that redefines the relationship between the plant and the city[iv].

The result is a futuristic geometric building clad with aluminium bricks and glass. The bricks doubly function as planters, to create the image of a green mountain with a white “snow” top from afar.

The ski slope expands upon the existing sport activities of the area and supports three different gradients (green, blue and black diamond runs) allowing novice to expert skiers. Skiers will be able to access the slope via an elevator along the smokestack. While Copenhill is currently operational, the slope is expected to open in the 2018 European autumn (Australia’s spring), and will be available to the public all year round.

Figure 4: Copenhill ski slope render

Figure 5: Copenhill climbing wall render

While waste plants are usually kept out of public view, at almost 100 meters tall Copenhill will be visible across most of the city’s skyline.

The plant’s chimney is not intended to emit exhaust continuously, but instead will puff one 30-meter wide “smoke” ring (non-toxic water vapour rather than smoke) every time 1 tonne of carbon dioxide (CO2) is released, to remind residents of their carbon footprint. It is proposed that, at night, a laser will project a pie chart onto the smoke ring, so the actual quota of CO2 can be viewed by locals.

The Plant

Copenhill replaces a neighbouring waste-incineration plant (Amagerforbrænding) that has produced district heat and electricity for 45 years.

It is being constructed by Amager Ressource Center (ARC), which is owned by five Danish municipalities. The combined heat and power plant will produce 25 per cent more energy than the plant it replaces, so 3 kilos of incinerated waste will light a bulb for five hours instead of four[v].

Copenhill is designed to utilise 100 per cent energy content of the waste. It will burn garbage from more than 500,000 residents and 46,000 companies in the greater Copenhagen area.

It is expected to treat around 400,000 tons of waste annually to supply a minimum of 50,000 Copenhagen homes with electricity and 120,000 households with district heating. And because it’s close to the city, it will provide hot water to 160,000 homes[vi].

Copenhill will also produce recycled materials (Figure 6). The plant will reuse 90 per cent of Copenhagen’s metal waste, recover 100 million litres of spare water through flue gas condensation, and reuse 100,000 tons of bottom ash as road material[vii].

Figure 6: Copenhill WtE plant

Source: Babcock & Wilcox Vølund A/S

Source: Babcock & Wilcox Vølund A/S

Due to catalytic filtration the incineration is nearly pollution-free. It will be the cleanest and most efficient WtE facility in the world. Cutting 107,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions annually (compared to a conventional coal-fired plant), it will also reduce nitrous oxides emissions by 85 per cent and the sulphur content of smoke by 99.5 per cent (compared to the existing plant)[viii].

Mixed reception

BIG unveiled their fantastical “Copenhill” idea to a mixed reception and it sparked debate in Denmark. Many Copenhagener’s felt that it wouldn’t eventuate, and in 2011, city officials rejected the facility pointing to an EA Energianalyse report that warned against building a new facility and instead suggested an upgrade of the existing plant.

ARC gained government support with the plant’s improvement when compared to the existing plant[ix]. The City Council approved plans for Copenhill in late 2012.

BIG’s tagline that Copenhill will provide “social, economic and environmental infrastructure” while changing “public perceptions of what a public utility should be,” will be proved. The group claim that Danes have since accepted Copenhill as one of the steps towards Copenhagen’s goal of becoming the world’s first carbon neutral capital by 2025. However there are concerns over the cost of the plant - most of which is expected to be covered from customers.

During its construction the combustion furnaces failed, resulting in an additional 13 million euros and a 7 month delay. The plant partially opened at the start of 2017 but by the middle of the year, it had experienced a technical failure, with one of the two incinerators breaking down. The failure stopped the plant’s ability to process tonnes of waste, forcing the facility to store it in plastic bags[x]. The Danish government allowed ARC to store the unprocessed waste until the problem had been fixed.

There are also suggestions that the plant is economically unsustainable due to an overcapacity of incineration. There isn't enough waste in Denmark to fill its 28 plants.

Copenhill has an annual capacity of around 400,000 tonnes, but the five municipalities that feed into the plant do not produce enough waste. It is expected to run under capacity and incur operational losses, a cost which is passed onto taxpayers[xi].

The plant’s original 2012 political agreement prohibited importing waste. A new agreement justifies the importing of waste rather than using landfills, yet EU regulation makes this hard. It’s expected that the plant will have to import between 90,000 and 115,000 tonnes of trash a year. There have been concerns that the importation of waste is only a short term solution, as other countries develop their own incineration plants and increase recycling programs.

According to Danish paper Murmur, the import of trash could also result in the burning of more plastic, potentially reversing-course and increasing the city’s carbon footprint.

“Imported trash typically consist of paper, cardboard and plastic – typically between 15 to 40 per cent plastic. In comparison, Danish waste contains an average of only 11 per cent plastic,” Jens Peter Mortensen, environmental expert at The Danish Society for Nature Conservation said in the paper[xii].

The city is looking to tourism to make the plant economically viable. It’s aiming to attract 300,000 visitors per year, with 65,000 being skiers.

Australia

While WtE plants have progressed in Europe, they are not so hot in Australia. Varying waste levies across states, transportation costs, and reliability of supply have all raised questions.

The plants have also raised community and environmental concern. For example, plans to build the world's largest waste incinerator in Western Sydney received concerns about air quality and human health impacts[xiv]. While plans for a plant in Canberra faced air quality concerns[xv].

In Victoria, the Andrews Government commissioned a series of public consultations on WtE technology. While there was “broad support” for WtE over landfill, residents were concerned about how pollution would be managed[xvi].

Preliminary ground-work has begun on what could be Australia’s first WtE facility. Phoenix Energy has received development and environmental approval for the Kwinana WtE Project in Western Australia. Expected to be completed by 2020, the facility will process 400,000 tonnes of waste a year and generate 40MW of energy[xvii].

While complex questions are still to be answered in Australia, Copenhill provides an alternative approach and could act as a test-case for the future potential of WtE plants.

[i] CenBio Final Report, 2017

[ii] CenBio is the Bioenergy Innovation Centre, one of Norway’s Centres for “environment-friendly” energy research co-founded by the Research Council of Norway.

[v] National Geographic, Urban Ski Slope to Raise Profile

[vi] Make Wealth History, Building of the Week

[vii] Progrss, Copenhagen’s Power Plant And Ski Slope

[viii] Power Technology, Amager Bakke Waste-to-Energy Plant

[ix] Zero Waste Europe, Denmark’s transition from incineration to Zero Waste

[x] Progrss, Copenhagen’s Power Plant And Ski Slope

[xi] Murmur, Copenhagen’s dirty white elephant

[xii] Murmur, Copenhagen’s dirty white elephant

[xiii] Capital Recycling Solutions, How a waste plant became Copenhagen’s biggest tourist attraction

[xiv] Sydney Morning Herald, Opposition Grows to Western Sydney incinerator

[xv] ABC, Plant to burn rubbish for energy faces uphill battle

[xvi] ABC, Waste energy plant for Melbourne proposed

[xvii] The West, WtE facility on the way

Related Analysis

International Energy Summit: The State of the Global Energy Transition

Australian Energy Council CEO Louisa Kinnear and the Energy Networks Australia CEO and Chair, Dom van den Berg and John Cleland recently attended the International Electricity Summit. Held every 18 months, the Summit brings together leaders from across the globe to share updates on energy markets around the world and the opportunities and challenges being faced as the world collectively transitions to net zero. We take a look at what was discussed.

Great British Energy – The UK’s new state-owned energy company

Last week’s UK election saw the Labour Party return to government after 14 years in opposition. Their emphatic win – the largest majority in a quarter of a century - delivered a mandate to implement their party manifesto, including a promise to set up Great British Energy (GB Energy), a publicly-owned and independently-run energy company which aims to deliver cheaper energy bills and cleaner power. So what is GB Energy and how will it work? We take a closer look.

Delivering on the ISP – risks and opportunities for future iterations

AEMO’s Integrated System Plan (ISP) maps an optimal development path (ODP) for generation, storage and network investments to hit the country’s net zero by 2050 target. It is predicated on a range of Federal and state government policy settings and reforms and on a range of scenarios succeeding. As with all modelling exercises, the ISP is based on a range of inputs and assumptions, all of which can, and do, change. AEMO itself has highlighted several risks. We take a look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.